6.2: Identidades pitagóricas

- Page ID

- 107175

El Teorema de Pitágoras trabaja sobre triángulos rectos. Si considera que la\(x\) coordenada de un punto a lo largo del círculo unitario es el coseno y la\(y\) coordenada del punto es el seno y la distancia al origen es 1 entonces el Teorema de Pitágoras inmediatamente produce la identidad:

\ (

\ begin {array} {l}

y^ {2} +x^ {2} =1\\

\ sin ^ {2} x+\ cos ^ {2} x=1

\ end {array}

\)

Un estudiante observador puede adivinar que existen otras identidades pitagóricas con el resto de funciones trigonométricas. ¿Es\(\tan ^{2} x+\cot ^{2} x=1\) una identidad legítima?

Identidades pitagóricas

La prueba de la identidad pitagórica para seno y coseno es esencialmente dibujar un triángulo rectángulo en un círculo unitario, identificando el coseno como la\(x\) coordenada, el seno como la\(y\) coordenada y 1 como la hipotenusa.

\(\cos ^{2} x+\sin ^{2} x=1\)

o

\(\sin ^{2} x+\cos ^{2} x=1\)

Las otras dos identidades pitagóricas son:

- \(1+\cot ^{2} x=\csc ^{2} x\)

- \(\tan ^{2} x+1=\sec ^{2} x\)

Para derivar estas dos identidades pitagóricas, dividir la identidad pitagórica original por\(\sin ^{2} x\) y\(\cos ^{2} x\) respectivamente.

Para derivar la identidad pitagórica\(1+\cot ^{2} x=\csc ^{2} x\) dividirla\(\sin ^{2} x\) y simplificarla.

\(\begin{aligned} \frac{\sin ^{2} x}{\sin ^{2} x}+\frac{\cos ^{2} x}{\sin ^{2} x} &=\frac{1}{\sin ^{2} x} \\ 1+\cot ^{2} x &=\csc ^{2} x \end{aligned}\)

De igual manera, para derivar la identidad pitagórica\(\tan ^{2} x+1=\sec ^{2} x\), dividirla\(\cos ^{2} x\) y simplificar.

\ begin {alineado}

\ frac {\ sin ^ {2} x} {\ cos ^ {2} x} +\ frac {\ cos ^ {2} x} {\ cos ^ {2} x} &=\ frac {1} {\ cos ^ {2} x}\

\ tan ^ {2} x+1 &=\ seg ^ {2} x

\ end {alineado}

Ejemplos

Anteriormente, se le preguntó si\(\tan ^{2} x+\cot ^{2} x=1\) es una identidad legítima. Las cofunciones no siempre están conectadas directamente a través de una identidad pitagórica.

\(\tan ^{2} x+\cot ^{2} x \neq 1\)

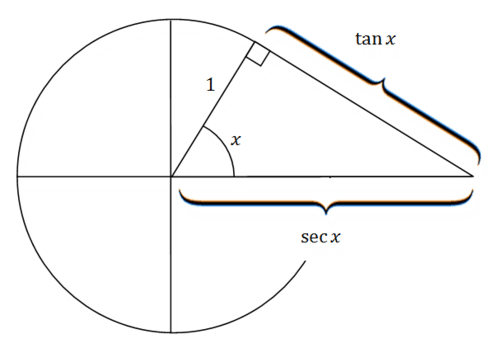

Visualmente, el triángulo rectángulo que conecta tangente y secante también se puede observar en el círculo unitario. La mayoría de la gente no sabe que tangente se denomina “tangente” porque se refiere a la distancia de la línea tangente desde el punto en el círculo unitario hasta el\(x\) eje. Mira la imagen de abajo y piensa en por qué tiene sentido eso\(\tan x\) y\(\sec x\) están como marcadas. \(\tan x=\frac{o p p}{a d j} .\)ya que el lado adyacente es igual a 1 (el radio del círculo), tan\(x\) simplemente equivale al lado opuesto. Una lógica similar puede explicar la ubicación de\(\sec x\).

Simplifica la siguiente expresión:\(\frac{\sin x(\csc x-\sin x)}{1-\sin x}\)

\ (

\ comenzar {alineado}

\ frac {\ sin x (\ csc x-\ sin x)} {1-\ sin x} &=\ frac {\ sin x\ cdot\ cdot\ csc x-\ sin ^ {2} x} {1-\ sin x}\\ sin}\\

&=\ frac {1-\ sin ^ {2} x} {1-\ sin x}\\

&= frac {(1-\ sin x) (1+\ sin x)} {1-\ sin x}\\

&=1+\ sin x

\ fin { alineado}

\)

Tenga en cuenta que factorizar la identidad pitagórica es una de las aplicaciones más potentes y comunes.

Demostrar la siguiente identidad trigonométrica. \(\left(\sec ^{2} x+\csc ^{2} x\right)-\left(\tan ^{2} x+\cot ^{2} x\right)=2\)

Agrupar los términos y aplicar una forma diferente de las dos segundas identidades pitagóricas que son\(1+\cot ^{2} x=\csc ^{2} x\) y\(\tan ^{2} x+1=\sec ^{2} x\)

\ (

\ begin {alineado}

\ izquierda (\ sec ^ {2} x+\ csc ^ {2} x\ derecha) -\ izquierda (\ tan ^ {2} x+\ cot ^ {2} x\ derecha) &=\ seg ^ {2} x-\ tan ^ {2} x+\ csc ^ {2} x-\ cot ^ {2} x\\

&=1+1\\

=2

\ final {alineado}

\)

Simplifica la siguiente expresión. Nota:\(\sec ^{2} x=\frac{1}{\cos ^{2} x}\)

\ (

\ begin {alineada}

\ izquierda (\ sec ^ {2} x\ derecha)\ izquierda (1-\ sin ^ {2} x\ derecha) -&\ izquierda (\ frac {\ sin x} {\ csc x} +\ frac {\ cos x} {\ seg x}\ derecha)\\

(&\ izquierda. \ sec ^ {2} x\ derecha)\ izquierda (1-\ sin ^ {2} x\ derecha) -\ izquierda (\ frac {\ sin x} {\ csc x} +\ frac {\ cos x} {\ sec x}\ derecha)\\

&=\ seg ^ {2} x\ cdot\ cos ^ {2} x-\ izquierda (\ sin ^ {2} x+\ cos ^ {2} x\ derecha)\\

&=1-1\\

&=0

\ end {alineado}

\)

Simplifica la siguiente expresión.

\ (

(\ cos t-\ sin t) ^ {2} + (\ cos t+\ sin t) ^ {2}

\)

Obsérvese que inicialmente, la expresión no es la misma que la identidad pitagórica.

\ (

\ begin {array} {l}

(\ cos t-\ sin t) ^ {2} + (\ cos t+\ sin t) ^ {2}\\

=\ cos ^ {2} t-2\ cos t\ sin t+\ sin ^ {2} t+\ cos ^ {2} t+2\ cos t\ sin t+\ sin ^ {2} t\

=1-2\ cos t\ sin t+1+2\ cos t\ sin t\\

=2

\ end {array}

\)

Revisar

Demostrar cada uno de los siguientes:

1. \(\left(1-\cos ^{2} x\right)\left(1+\cot ^{2} x\right)=1\)

2. \(\cos x\left(1-\sin ^{2} x\right)=\cos ^{3} x\)

3. \(\sin ^{2} x=(1-\cos x)(1+\cos x)\)

4. \(\sin x=\frac{\sin ^{2} x+\cos ^{2} x}{\csc x}\)

5. \(\sin ^{4} x-\cos ^{4} x=\sin ^{2} x-\cos ^{2} x\)

6. \(\sin ^{2} x \cos ^{3} x=\left(\sin ^{2} x-\sin ^{4} x\right)(\cos x)\)

Simplifica cada expresión tanto como sea posible.

7. \(\tan ^{3} x \csc ^{3} x\)

8. \(\frac{\csc ^{2} x-1}{\sec ^{2} x}\)

9. \(\frac{1-\sin ^{2} x}{1+\sin x}\)

10. \(\sqrt{1-\cos ^{2} x}\)

11. \(\frac{\sin ^{2} x-\sin ^{4} x}{\cos ^{2} x}\)

12. \(\left(1+\tan ^{2} x\right)\left(\sec ^{2} x\right)\)

13. \(\frac{\sin ^{2} x+\tan ^{2} x+\cos ^{2} x}{\sec x}\)

14. \(\frac{1+\tan ^{2} x}{\csc ^{2} x}\)

15. \(\frac{1-\sin ^{2} x}{\cos x}\)

...