2.14: Modulación de amplitud en cuadratura

- Page ID

- 83348

Los esquemas de modulación digital descritos hasta ahora modulan la fase o frecuencia de una portadora para transportar datos digitales y los puntos de constelación se encuentran en un círculo de amplitud constante. El efecto de esto es proporcionar cierta inmunidad a los cambios de amplitud de la señal. Sin embargo, se puede transmitir mucha más información si se varía la amplitud así como la fase. Con un procesamiento de señal considerable es posible utilizar de manera confiable la modulación de amplitud en cuadratura (QAM) en la que tanto la amplitud como la fase se cambian.

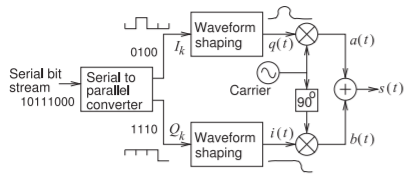

Una constelación QAM rectangular de\(16\) estado, 16-QAM, se muestra en la Figura 2.8.18 (c). Dado que hay\(16 (= 2^{4})\) símbolos, los valores de los bits\(4\) binarios se especifican de manera única por cada símbolo. En la Figura 2.8.18 (c) se muestra una asignación en escala de grises de valores de\(4\) bits. En la Figura 2.8.20 se muestran varios esquemas QAM. Estas constelaciones se pueden producir modulando por amplitud por separado una\(I\) portadora y una\(Q\) portadora. Ambas portadoras tienen la misma frecuencia pero están\(90^{\circ}\) desfasadas. Las dos portadoras se combinan entonces de manera que se suprime la portadora fija. La forma más común de QAM es QAM cuadrada, o QAM rectangular con un número igual de\(I\) y\(Q\) estados. Las formas más comunes son

Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\): Diagrama de bloques del modulador QAM. En QAM modulación\(i(t)\) y\(q(t)\) abordar los componentes reales e imaginarios de un fasor. El bloque de conformación de onda asegura que el símbolo tenga la amplitud y fase correctas en cada tick de reloj.

| Modulación | \(\text{bits/s/Hz}\) |

|---|---|

| BPSK (ideal) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(1\) |

| BFSK (real) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(1\) |

| QPSK (ideal) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(2\) |

| GMSK (un método FSK real) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(1.354\) |

| \(π/4\)-DQPSK (un método QPSK real) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(1.63\) |

| 8-PSK (ideal) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(3\) |

| \(3π/8\)-8PSK (un método 8PSK real) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(2.7\) |

| 16-QAM (ideal) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(4\) |

| 16-QAM (real) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(2.98\) |

| 32-QAM (ideal) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(4\) |

| 32-QAM (real) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(3.35\) |

| 64-QAM (ideal) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(6\) |

| 64-QAM (real) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(4.47\) |

| 256-QAM (ideal) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(8\) |

| 256-QAM (televisión real, por satélite y por cable) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(6.33\) |

| 512-QAM (ideal) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(9\) |

| 1024-QAM (ideal) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(10\) |

| 2048-QAM (ideal) | \ (\ text {bits/s/Hz}\) ">\(11\) |

Tabla\(\PageIndex{1}\): Eficiencias de modulación de diversos formatos de modulación en\(\text{bits/s/Hz}\) (bits por segundo por hercio). Las eficiencias de modulación máximas (o ideales) obtenidas por los esquemas de modulación (por ejemplo, BPSK, BFSK, 64- QAM, 256-QAM) dan como resultado amplios espectros. Las eficiencias reales de modulación logradas son menores en un esfuerzo por administrar el ancho de banda. Por ejemplo, los valores para\(pi/4\) -DQPSK y\(3pi/8\) -8PSK son reales. Esta reducción de ideal surge ya que las transiciones de símbolos son de diferentes longitudes y la longitud corresponde a duraciones de tiempo. Dado que el intervalo de símbolos es fijo, es la ruta más larga la que determina el ancho de banda requerido.

16-QAM, 64-QAM y 128-QAM, en 4G, y 256-QAM adicionalmente en 5G. Los puntos de constelación están más cerca junto con QAM de alto orden y por lo tanto son más susceptibles al ruido y otras interferencias. Por lo tanto, QAM de orden superior puede entregar más datos, pero de manera menos confiable que QAM de orden inferior.

La constelación en QAM se puede construir de muchas maneras, y mientras que la QAM rectangular es la forma más común, existen esquemas no rectangulares; por ejemplo, tener dos esquemas PSK en dos niveles de amplitud diferentes. Si bien a veces hay ventajas menores en tales esquemas, generalmente se prefiere QAM cuadrado ya que requiere una modulación y demodulación más simples.

Una posible arquitectura de un modulador QAM se muestra en la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) y esto solo se puede implementar en DSP ya que no es suficiente usar filtrado paso bajo analógico para implementar la función de conformación de onda como el\(i(t)\) y\(q(t)\) debe ser precisamente las partes reales e imaginarias del símbolo en cada marca de reloj.