5.2: Ecuaciones del Telégrafo

- Page ID

- 86488

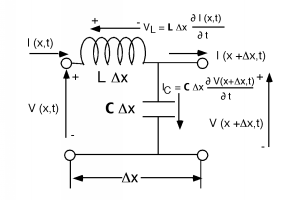

Veamos solo una pequeña sección de la línea, y definamos algunos voltajes y corrientes como en la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\).

Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\): Aplicación de las leyes de Kirchoff

Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\): Aplicación de las leyes de Kirchoff

Para la sección de línea\(Delta x\) larga, el voltaje en su entrada es justo\(V(x, t)\) y el voltaje en la salida es\(V(x + \Delta x, t)\). De igual manera, tenemos una corriente\(I(x, t)\) entrando al tramo, y otra corriente\(I(x + \Delta x, t)\) que sale del tramo de línea. Tenga en cuenta que tanto el voltaje como la corriente son funciones de tiempo así como de posición.

La caída de voltaje a través del inductor es solo:\[V_{L} = \mathbf{L} \Delta (x) \frac{\partial I(x, t)}{\partial t}\]

Del mismo modo, la corriente que fluye hacia abajo a través del condensador es\[I_{C} = \mathbf{C} \Delta (x) \frac{\partial V(x + \Delta (x), t)}{\partial t}\]

Ahora hacemos un KVL alrededor del exterior de la sección de línea y obtenemos\[V(x, t) - V_{L} - V(x + \Delta (x), t) = 0\]

Sustituyendo\(\PageIndex{1}\) la ecuación\(V_{L}\) y llevándola al lado derecho, tenemos\[V(x, t) - V(x + \Delta (x), t) = \mathbf{L} \Delta (x) \frac{\partial I(x, t)}{\partial t}\]

Multipliquemos esto por\(-1\), y llevemos el\(\Delta (x)\) sobre al lado izquierdo. \[\frac{V(x + \Delta (x), t) - V(x, t)}{\Delta (x)} = - \left( \mathbf{L} \frac{\partial I(x, t)}{\partial t}\right)\]

Tomamos el límite como\(\Delta (x) \rightarrow 0\) y el LHS se convierte en un derivado:\[\frac{\partial V(x, t)}{\partial x} = - \left(\mathbf{L} \frac{\partial I(x, t)}{\partial t}\right)\]

Ahora podemos hacer un KCL en el nodo donde se unen el inductor y el condensador. \[I(x, t) - \mathbf{C} \Delta (x) \frac{\partial V(x + \Delta (x), t)}{\partial t} - I(x + \Delta (x), t) = 0\]

Y tras el reordenamiento:\[\frac{I(x + \Delta (x), t) - I(x, t)}{\Delta (x)} = -\left(\mathbf{C} \frac{\partial V(x + \Delta (x), t)}{\partial t}\right)\]

Ahora cuando dejamos\(\Delta (x) \rightarrow 0\), el lado izquierdo vuelve a ser un derivado, y en el lado derecho\(V(x + \Delta (x), t) \rightarrow V(x, t)\), entonces tenemos:\[\frac{\partial V(x, t)}{\partial x} = - \left(\mathbf{C} \frac{\partial V(x, t)}{\partial t}\right)\]

Ecuación\(\PageIndex{6}\) y Ecuación\(\PageIndex{9}\) son tan importantes que volveremos a escribirlas juntas:\[\frac{\partial V(x, t)}{\partial x} = -\left(\mathbf{L} \frac{\partial I(x, t)}{\partial t}\right)\]\[\frac{\partial I(x, t)}{\partial x} = -\left(\mathbf{C} \frac{\partial V(x, t)}{\partial t}\right)\]

Estas se llaman ecuaciones del telégrafo, y son todo lo que realmente necesitamos para derivar cómo se comportan las señales eléctricas a medida que avanzan en las líneas de transmisión. Tenga en cuenta lo que dicen. El primero dice que en algún momento a\(x\) lo largo de la línea, la caída de voltaje incremental que experimentamos a medida que bajamos de la línea es solo la inductancia distribuida\(\mathbf{L}\) multiplicada por el tiempo derivado de la corriente que fluye en la línea en ese punto. La segunda ecuación simplemente nos dice que la pérdida de corriente a medida que bajamos por la línea es proporcional a la capacitancia distribuida\(\mathbf{C}\) multiplicada por la tasa de tiempo de cambio de la tensión en la línea. Como debe ser fácilmente consciente, lo que tenemos aquí son un par de ecuaciones diferenciales lineales acopladas en tiempo y posición para\(V(x, t)\) y\(I(x, t)\).