1.4: Señales de tiempo continuas comunes

- Page ID

- 86598

Introducción

Antes de mirar este módulo, ojalá tengas una idea de qué es una señal y qué clasificaciones y propiedades básicas puede tener una señal. En revisión, una señal es una función definida con respecto a una variable independiente. Esta variable suele ser tiempo pero podría representar cualquier número de cosas. Matemáticamente, las señales analógicas de tiempo continuas tienen variables independientes y dependientes continuas. Este módulo describirá algunas señales analógicas de tiempo continuas útiles.

Señales de tiempo continuas importantes

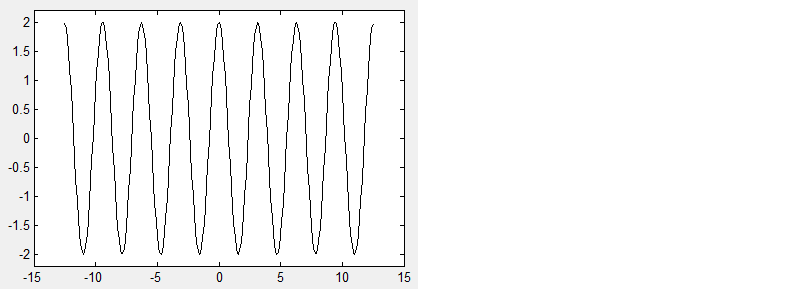

Sinusoides

Una de las señales elementales más importantes con las que tratarás es la sinusoide de valor real. En su forma de tiempo continuo, escribimos la expresión general como

\[A \cos (\omega t+\varphi) \label{1.32} \]

donde\(A\) esta la amplitud,\(\omega\) es la frecuencia, y\(\varphi\) es la fase. Así, el periodo de la sinusoide es

\[ T = \frac{2 \pi}{\omega} \label{1.33} \]

Exponenciales Complejos

Tan importante como la sinusoide general, la compleja función exponencial se convertirá en una parte crítica de su estudio de señales y sistemas. Su forma general continua está escrita como

\[A e^{s t} \nonumber \]

donde\(s=\sigma+j \omega\) es un número complejo en términos de\(\sigma\), la constante de atenuación y\(\omega\) la frecuencia angular.

Impulsos unitarios

La función de impulso unitario, también conocida como la función delta de Dirac, es una señal que tiene altura infinita y ancho infinitesimal. No obstante, por la forma en que se define, se integra a uno. Si bien esta señal es útil para la comprensión de muchos conceptos, una comprensión formal de su definición más involucrada. El impulso unitario se denota comúnmente δ (t) δ t.

Se brinda más detalle en la sección sobre la función de impulso de tiempo continuo. Por ahora, basta decir que esta señal es de vital importancia en el estudio de las señales continuas, ya que permite que la propiedad de tamizado sea utilizada en la representación de la señal y descomposición de la señal.

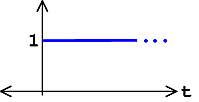

Paso de Unidad

Otra señal muy básica es la función unidad-paso que se define como

\ [u (t) =\ left\ {\ begin {array} {l}

0\ text {if} t<0\\

1\ text {if} t\ geq 0

\ end {array}\ right. \ nonumber\]

La función step es una herramienta útil para probar y definir otras señales. Por ejemplo, cuando diferentes versiones cambiadas de la función de paso se multiplican por otras señales, se puede seleccionar una cierta porción de la señal y eliminar el resto a cero.

Resumen de señales de tiempo continuas comunes

Algunas de las señales más importantes y frecuentemente encontradas han sido discutidas en este módulo. Hay, por supuesto, muchas otras señales de consecuencias significativas que no se discuten aquí. Como verá más adelante, muchas de las otras señales más complicadas serán estudiadas en términos de las que aquí se enumeran. Especialmente tomar nota de los exponenciales complejos y funciones de impulso unitario, que serán el foco clave de varios temas incluidos en este curso.