7.1: Tiempo Discreto Señales Periódicas

- Page ID

- 86492

Introducción

Este módulo describe el tipo de señales sobre las que actúa la Serie Discreta de Fourier de Tiempo.

Espacios Relevantes

La Serie de Fourier de Tiempo Discreto mapea señales de tiempo discretas de longitud finita (o\(N\) -periódica) en\(L^2\) longitud finita, señales de frecuencia discreta en\(l^2\).

Las señales periódicas en tiempo discreto se repiten en cada ciclo. Sin embargo, solo se permiten números enteros como variables de tiempo en tiempo discreto. Denotamos señales en tal caso como\(x[n]\),\(n=\ldots,-2,-1,0,1,2, \dots\)

Señales Periódicas

Cuando una función se repite exactamente después de algún periodo, o ciclo dado, decimos que es periódica. Una función periódica puede definirse matemáticamente como:

\[f[n]=f[n+m N] \forall m:(m \in \mathbb{Z}) \label{7.1} \]

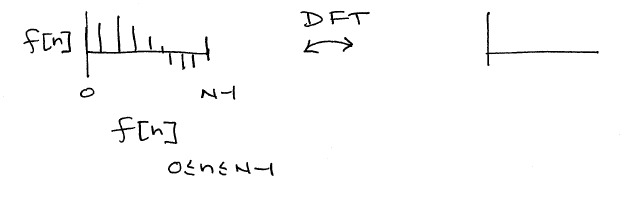

donde\(N > 0\) representa el periodo fundamental de la señal, que es el valor positivo más pequeño de N para que la señal se repita. Debido a esto, es posible que también vea una señal denominada señal N-periódica. Cualquier función que satisfaga esta ecuación se dice que es periódica con el período N. Aquí hay un ejemplo de una señal periódica de tiempo discreto con el período N:

Podemos pensar en funciones periódicas (con punto\(N\)) de dos maneras diferentes:

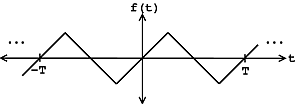

- como funciones en todos\(\mathbb{R}\)

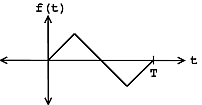

Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\): función periódica de tiempo discreto sobre todo\(\mathbb{R}\) donde\(f[n_0]=f[n_0+N]\) - o, podemos cortar toda la redundancia, y pensar en ellas como funciones en un intervalo\([0,N]\) (o, más generalmente,\([a, a+N]\)). Si sabemos que la señal es N-periódica entonces toda la información de la señal es capturada por el intervalo anterior.

Figura\(\PageIndex{4}\): Eliminar la redundancia de la función period para que\(f[n]\) quede indefinida afuera\([0,N]\).

Una función DT aperiódica\(f[n]\) no se repite para ninguna\(N \in \mathbb{R}\); es decir, no existe\(N\) tal que la Ecuación\ ref {7.1} mantenga.

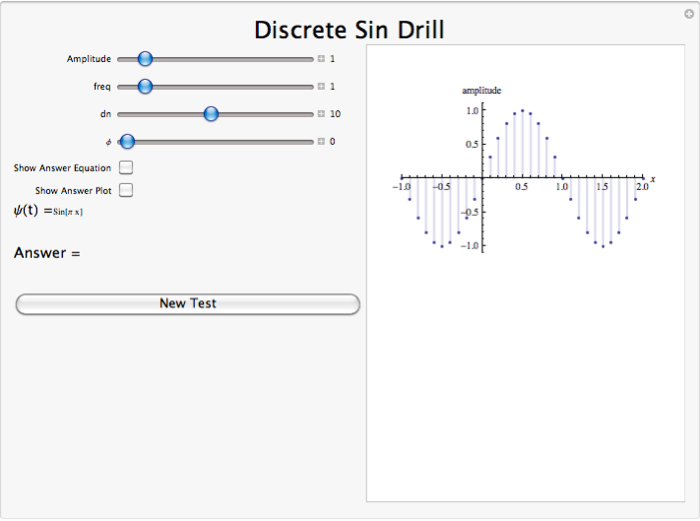

Demostración SinDrillDiscrete

Aquí hay un ejemplo que demuestra una señal sinusoidal periódica con varias frecuencias, amplitudes y retardos de fase:

Conclusión

Una señal periódica discreta está completamente definida por sus valores en un periodo, como el intervalo [0, N].