15.4: Productos internos

- Page ID

- 86584

Definición: Producto interno

Es posible que hayas encontrado productos internos, también llamados productos punto,\(\mathbb{R}^n\) antes en algunos de tus cursos de matemáticas o ciencias. Si no, definimos el producto interno de la siguiente manera, dado que tenemos algunos\(\boldsymbol{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{n}\) y\(\boldsymbol{y} \in \mathbb{R}^{n}\).

Definición: Producto interno estándar

El producto interno estándar se define matemáticamente como:

\ [\ begin {alineado}

\ langle\ negridsymbol {x},\ negridsymbol {y}\ rangle &=\ negritas {y} ^ {T}\ símbolo en negrita {x}\\

&=\ izquierda (\ begin {array} {cccc}

y_ {0} & y_ {1} &\ dots & y_ {n-1}

\ end {array}\ derecha)\ left (\ begin {array} {c}

x_ {0}\\

x_ {1}\\

\ vdots\\

x_ {n-1}

\ end {array}\ derecha)\\

&=\ suma_ {i=0} ^ {n-1} x_ {i} y_ {i}

\ end {alineado}\ nonumber\]

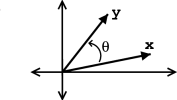

Producto interno en 2-D

Si tenemos\(\boldsymbol{x} \in \mathbb{R}^2\) y\(\boldsymbol{y} \in \mathbb{R}^2\), entonces podemos escribir el producto interno como

\[\langle\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle=\|\boldsymbol{x}\|\|\boldsymbol{y}\| \cos (\theta) \nonumber \]

donde\(\theta\) esta el angulo entre\(\boldsymbol{x}\) y\(\boldsymbol{y}\).

Geométricamente, el producto interno nos habla de la fuerza de\(\boldsymbol{x}\) en la dirección de\(\boldsymbol{y}\).

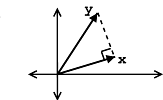

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Por ejemplo, si\(\|x\|=1\), entonces

\[<x, y>=\|y\| \cos (\theta) \nonumber \]

Las siguientes características son reveladas por el producto interno:

- \(\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle\)mide la longitud de la proyección de\(\boldsymbol{y}\) sobre\(\boldsymbol{x}\).

- \(\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle\)es máximo (para dado\(\|\boldsymbol{x}\|\),\(\|\boldsymbol{y}\|\)) cuando\(\boldsymbol{x}\) y\(\boldsymbol{y}\) están en la misma dirección (\((\theta=0) \Rightarrow(\cos (\theta)=1)\)).

- \(\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle\)es cero cuando\((\cos (\theta)=0) \Rightarrow\left(\theta=90^{\circ}\right)\), es decir,\(\boldsymbol{x}\) y\(\boldsymbol{y}\) son ortogonales.

Reglas internas del producto

En general, un producto interno en un espacio vectorial complejo es solo una función (tomar dos vectores y devolver un número complejo) que satisface ciertas reglas:

- Simetría conjugada:\[\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle=\overline{\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle} \nonumber \]

- Escalado:\[\langle\alpha \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y} \rangle=\alpha\langle(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y})\rangle \nonumber \]

- Aditividad:\[\langle \boldsymbol{x}+\boldsymbol{y}, \boldsymbol{z} \rangle=\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle+\langle \boldsymbol{y}, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle \nonumber \]

- “Positividad”:\[\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{x} \rangle >0, \boldsymbol{x} \neq 0 \nonumber \]

Definición: Ortogonal

Nosotros decimos eso\(\boldsymbol{x}\) y\(\boldsymbol{y}\) son ortogonales si:

\[\langle\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle=0 \nonumber \]