6.5: Promedios exponenciales y filtros recursivos

- Page ID

- 82421

Supongamos que intentamos extender nuestro método para calcular promedios móviles finitos a promedios móviles infinitos de la forma

\ [\ begin {align}

x_ {n} &=\ qquad\ qquad\ qquad\ suma_ {k=0} ^ {\ infty} w_ {k} u_ {n-k}\ nonumber\\

&=w_ {0} u_ {n} +w_ {1} u_ {n-1} +\ cdots+w_ {1000} u_ {n-1000} +\ cdots

\ end {align}\ nonumber\]

En general, esta media móvil requeriría memoria infinita para los coeficientes de ponderación\(w_{0}, w_{1}, \ldots\) y para las entradas\(u_{n}, u_{n-1}, \ldots\). Además, el hardware para multiplicar wkun−kwkun-k tendría que ser infinitamente rápido para calcular la media móvil infinita en tiempo finito. Todo esto es claramente fantasioso e inverosímil (sin mencionar imposible). Pero, ¿y si los pesos toman la forma exponencial

\[w_{k}= \begin{cases}0, & k<0 \\ w_{0} a^{k}, & k \geq 0 ?\end{cases} \nonumber \]

¿Algún resultado de simplificación? Hay esperanza porque la secuencia de ponderación obedece a la recursión

\[w_{k}= \begin{cases}0, & k<0 \\ w_{0}, & k=0 \\ a w_{k-1} & k \geq 1\end{cases} \nonumber \]

Esta recursión puede ser reescrita de la siguiente manera, para\(k \geq 1\):

\[w_{k}-a w_{k-1}=0, k \geq 1 \nonumber \]

Ahora manipulemos la media móvil infinita y utilicemos la recursión para los pesos para ver qué sucede. Debes seguir cada paso:

\ [\ begin {align}

x_ {n} &=\ suma_ {k=0} ^ {\ infty} w_ {k} u_ {n-k}\ nonumber\\

&=\ quad\ suma_ {k=1} ^ {\ infty} w_ {k} u_ {n-k} +w_ {0} u_ {n}\ nonúmero\\

&= _ {k=1} ^ {\ infty} a w_ {k-1} u_ {n-k} +w_ {0} u_ {n}\ nonumber\\

&=a\ suma_ {m=0} ^ {\ infty} w_ {m} u_ {n-1- m} +w_ {0} u_ {n}\ nonumber\\

&=a x_ {n-1} +w_ {0} u_ {n}.

\ end {align}\ nonumber\]

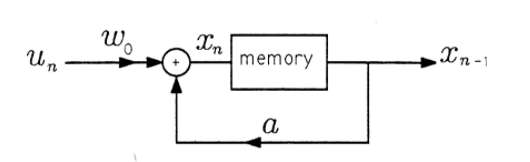

Este resultado es fundamentalmente importante porque dice que la salida de la media móvil exponencial infinita puede calcularse escalando la salida anterior\(x_{n-1}\) por la constante\(a\), escalando la nueva entrada\(u_n\) por\(w_0\), y sumando. Solo se deben asignar tres ubicaciones de memoria: una para\(w_0\), una para\(a\) y otra para\(x_{n-1}\). Sólo se deben implementar dos multiplicaciones: una para\(ax_{n-1}\) y otra para\(w_0u_n\). En la Figura 1 se da un diagrama de la recursión. En esta recursión, el antiguo valor de la media móvil exponencial\(x_{n-1}\),, se escala\(a\) y se suma\(w_0u_n\) para producir la nueva media móvil exponencial\(x_n\). Este nuevo valor se almacena en la memoria, donde se convierte\(x_{n-1}\) en el siguiente paso de la recursión, y así sucesivamente.

Intentar extender la recursión de los párrafos anteriores al promedio ponderado

\(x_{n}=\sum_{k=0}^{N-1} a^{k} u_{n-k} .\)

¿Qué sale mal?

Calcular la salida de la media móvil exponencial\(x_{n}=a x_{n-1}+w_{0} u_{n}\) cuando la entrada es

\(u_{n}= \begin{cases}0, & n<0 \\ u, & n \geq 0\end{cases}\)

Traza tu resultado versus\(n\).

Calcular\(w_0\) en la secuencia de ponderación exponencial

\(w_{n}= \begin{cases}0, & n<0 \\ a^{n} w_{0}, & n \geq 0\end{cases}\)

para que la secuencia de ponderación sea una ventana válida. (Este es un caso especial del Ejercicio 3 de Filtrado: Promedios Móviles.) Asumir\(−1<a<1\)