10.1: Resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas usando la propiedad de raíz cuadrada

- Page ID

- 110201

Al final de esta sección, podrás:

- Resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas de la forma\(ax^2=k\) usando la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada

- Resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas de la forma\(a(x−h)^2=k\) usando la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada

- Simplificar:\(\sqrt{75}\).

- Simplificar:\(\sqrt{\dfrac{64}{3}}\)

- Factor:\(4x^{2} − 12x + 9\).

Las ecuaciones cuadráticas son ecuaciones de la forma\(ax^{2} + bx + c = 0\), donde\(a \neq 0\). Se diferencian de las ecuaciones lineales al incluir un término con la variable elevada a la segunda potencia. Utilizamos diferentes métodos para resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas s que ecuaciones lineales, porque solo sumar, restar, multiplicar y dividir términos no aislará la variable.

Hemos visto que algunas ecuaciones cuadráticas pueden resolverse factorizando. En este capítulo, utilizaremos otros tres métodos para resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas.

Resolver Ecuaciones Cuadráticas de la Forma\(ax^2=k\) Usando la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada

Ya hemos resuelto algunas ecuaciones cuadráticas por factorización. Revisemos cómo se utilizó el factoring para resolver la ecuación cuadrática\(x^{2} = 9\).

\[\begin{array}{ll} {}&{x^2=9}\\ {\text{Put the equation in standard form.}}&{x^2−9=0}\\ {\text{Factor the left side.}}&{(x - 3)(x + 3) = 0}\\ {\text{Use the Zero Product Property.}}&{(x - 3) = 0, (x + 3) = 0}\\ {\text{Solve each equation.}}&{x = 3, x = -3}\\ {\text{Combine the two solutions into} \pm \text{form}}&{x=\pm 3}\\ \nonumber \end{array}\]

(La solución se lee '\(x\)es igual a positivo o negativo\(3\).')

Podemos usar fácilmente el factoring para encontrar las soluciones de ecuaciones similares, como\(x^{2}=16\) y\(x^{2} = 25\), porque\(16\) y\(25\) son cuadrados perfectos. Pero, ¿qué pasa cuando tenemos una ecuación como\(x^{2}=7\)? Como no\(7\) es un cuadrado perfecto, no podemos resolver la ecuación factorizando.

Estas ecuaciones son todas de la forma\(x^{2}=k\).

Definimos la raíz cuadrada de un número de esta manera:

Si\(n^{2} = m\), entonces\(n\) es una raíz cuadrada de\(m\).

Esto lleva a la Propiedad de Raíz Cuadrada.

Si\(x^{2}=k\), y\(k \geq 0\), entonces\(x = \sqrt{k}\) o\(x = -\sqrt{k}\).

Observe que la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada da dos soluciones a una ecuación de la forma\(x^2=k\): la raíz cuadrada principal de k y su opuesta. También podríamos escribir la solución como\(x=\pm \sqrt{k}\)

Ahora, volveremos a resolver la ecuación, esta\(x^{2} = 9\) vez usando la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada.

\[\begin{array}{ll} {}&{x^{2} = 9}\\ {\text{Use the Square Root Property.}}&{x = \pm\sqrt{9}}\\ {\text{Simplify the radical.}}&{x = \pm 3}\\ {\text{Rewrite to show the two solutions.}}&{x = 3, x = −3}\\ \nonumber \end{array}\]

¿Qué pasa cuando la constante no es un cuadrado perfecto? Usemos la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada para resolver la ecuación\(x^2=7\).

\[\begin{array} {ll} {\text{Use the Square Root Property. }}&{x = \pm\sqrt{7}}\\ {\text{Rewrite to show two solutions.}}&{x = \sqrt{7}, x = −\sqrt{7}}\\ {\text{We cannot simplify} \sqrt{7} \text{ so we leave the answer as a radical.}}&{}\\ \nonumber \end{array}\]

Resolver:\(x^{2} = 169\)

- Contestar

-

\[\begin{array}{ll} {}&{x^2=169}\\ {\text{Use the Square Root Property.}}&{x=\pm\sqrt{169}}\\ {\text{Simplify the radical.}}&{x = \pm13}\\{\text{Rewrite to show two solutions.}}&{x = 13, x = −13}\\ \nonumber \end{array}\]

Resolver:\(x^2=81\)

- Contestar

-

x=9, x=−9

Resolver:\(y^{2} = 121\)

- Contestar

-

y = 11, y = −11

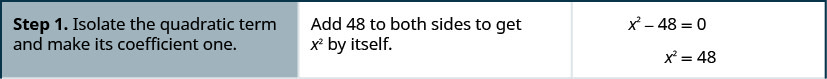

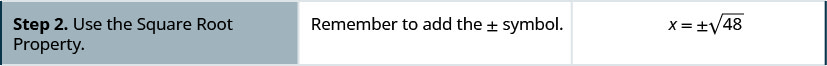

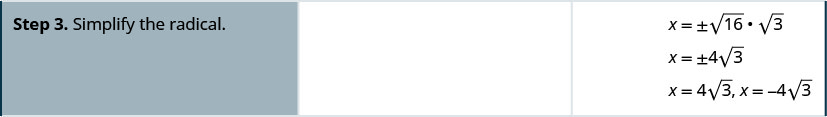

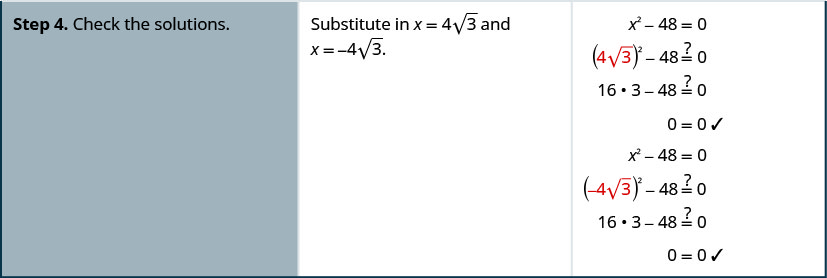

Cómo Resolver una Ecuación Cuadrática de la Forma\(ax^{2} = k\) Usando la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada

Resolver:\(x^{2} − 48 = 0\)

- Contestar

Resolver:\(x^{2} − 50 = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(x = 5\sqrt{2}, x = −5\sqrt{2}\)

Resolver:\(y^{2} − 27 = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(y = 3\sqrt{3}, x = −3\sqrt{3}\)

- Aísle el término cuadrático y haga su coeficiente uno.

- Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada.

- Simplifica lo radical.

- Consulta las soluciones.

Para utilizar la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada, el coeficiente del término variable debe ser igual a 1. En el siguiente ejemplo, debemos dividir ambos lados de la ecuación por 5 antes de usar la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada.

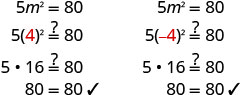

Resolver:\(5m^2=80\)

- Contestar

-

El término cuadrático es aislado. \(5m^2=80\) Dividir por 5 para hacer su cofficient 1. \(\frac{5m^2}{5}=\frac{80}{5}\) Simplificar. \(m^2=16\) Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada. \(m=\pm\sqrt{16}\) Simplifica lo radical. \(m=\pm 4\) Reescribe para mostrar dos soluciones. m=4, m=−4 Consulta las soluciones.

Resolver:\(2x^2=98\).

- Contestar

-

x=7, x=−7

Resolver:\(3z^2=108\).

- Contestar

-

z=6, z=−6

La Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada comenzó diciendo, 'Si\(x^2=k\), y\(k\ge 0\) '. ¿Qué pasará si\(k<0\)? Este será el caso en el siguiente ejemplo.

Resolver:\(q^2+24=0\).

- Contestar

-

\[\begin{array}{ll} {}&{q^2=24}\\ {\text{Isolate the quadratic term.}}&{q^2=−24}\\ {\text{Use the Square Root Property.}}&{q=\pm\sqrt{-24}}\\ {\text{The} \sqrt{-24} \text{is not a real number}}& {\text{There is no real solution}}\\ \nonumber \end{array}\]

Resolver:\(c^2+12=0\).

- Contestar

-

ninguna solución real

Resolver:\(d^2+81=0\).

- Contestar

-

ninguna solución real

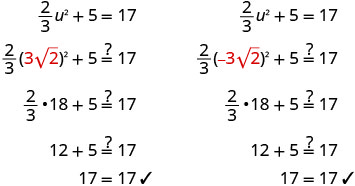

Resolver:\(\frac{2}{3}u^2+5=17\).

- Contestar

-

\(\frac{2}{3}u^2+5=17\) Aislar el término cuadrático. \(\frac{2}{3}u^2=12\)

\(\frac{3}{2}\)Multiplicar por para hacer el coeficiente 1. \(\frac{3}{2}·\frac{2}{3}u^2=\frac{3}{2}·12\) Simplificar. \(u^2=18\) Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada. \(u=\pm\sqrt{18}\) Simplifica lo radical. \(u=\pm\sqrt{9}\sqrt{2}\) Simplificar. \(u=\pm3\sqrt{2}\) Reescribe para mostrar dos soluciones. \(u=3\sqrt{2}\),\(u=−3\sqrt{2}\) Cheque.

Resolver:\(\frac{1}{2}x^2+4=24\)

- Contestar

-

\(x=2\sqrt{10}\),\(x=−2\sqrt{10}\)

Resolver:\(\frac{3}{4}y^2−3=18\).

- Contestar

-

\(y=2\sqrt{7}\),\(y=−2\sqrt{7}\)

Las soluciones a algunas ecuaciones pueden tener fracciones dentro de los radicales. Cuando esto sucede, debemos racionalizar el denominador.

Resolver:\(2c^2−4=45\).

- Contestar

-

\(2c^2−4=45\) Aislar el término cuadrático. \(2c^2=49\) Dividir por 2 para hacer el coeficiente 1. \(\frac{2c^2}{2}=\frac{49}{2}\) Simplificar. \(c^2=\frac{49}{2}\) Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada. \(c=\pm\frac{\sqrt{49}}{\sqrt{2}}\) Simplifica lo radical. \(c=\pm\frac{\sqrt{49}}{\sqrt{2}}\) Racionalizar el denominador. \(c=\pm\frac{\sqrt{49}\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2}\sqrt{2}}\) Simplificar. \(c=\pm\frac{7\sqrt{2}}{2}\) Reescribe para mostrar dos soluciones. \(c=\frac{7\sqrt{2}}{2}\),\(c=−\frac{7\sqrt{2}}{2}\) Cheque. Te dejamos el cheque.

Resolver:\(5r^2−2=34\).

- Contestar

-

\(r=\frac{6\sqrt{5}}{5}\),\(r=−\frac{6\sqrt{5}}{5}\)

Resolver:\(3t^2+6=70\).

- Contestar

-

\(t=\frac{8\sqrt{3}}{3}\),\(t=−\frac{8\sqrt{3}}{3}\)

Resolver Ecuaciones Cuadráticas de la Forma\(a(x-h)^2=k\) Usando la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada

Podemos usar la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada para resolver una ecuación como\((x−3)^2=16\), también. Trataremos todo el binomio, (x−3), como el término cuadrático.

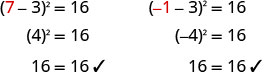

Resolver:\((x−3)^2=16\).

- Contestar

-

\((x−3)^2=16\) Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada. \(x−3=\pm\sqrt{16}\) Simplificar. \(x−3=\pm 4\) Escribe como dos ecuaciones. \(x−3=4\),\(x−3=−4\) Resolver. x=7, x=−1 Cheque.

Resolver:\((q+5)^2=1\).

- Contestar

-

q=−6, q=−4

Resolver:\((r−3)^2=25\).

- Contestar

-

r=8, r=−2

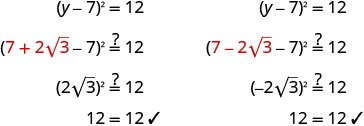

Resolver:\((y−7)^2=12\).

- Contestar

-

\((y−7)^2=12\). Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada. \(y−7=\pm\sqrt{12}\) Simplifica lo radical. \(y−7=\pm2\sqrt{3}\) Resolver por y. \(y=7\pm2\sqrt{3}\) Reescribe para mostrar dos soluciones. \(y=7+2\sqrt{3}\),\(y=7−2\sqrt{3}\) Cheque.

Resolver:\((a−3)^2=18\).

- Contestar

-

\(a=3+3\sqrt{2}\),\(a=3−3\sqrt{2}\)

Resolver:\((b+2)^2=40\).

- Contestar

-

\(b=−2+2\sqrt{10}\),\(b=−2−2\sqrt{10}\)

Resolver:\((x−\frac{1}{2})^2=\frac{5}{4}\).

- Contestar

-

\((x−\frac{1}{2})^2=\frac{5}{4}\) Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada. \((x−\frac{1}{2})=\pm\sqrt\frac{5}{4}\) Reescribir el radical como una fracción de raíces cuadradas. \((x−\frac{1}{2})=\pm\frac{\sqrt{5}}{\sqrt{4}}\) Simplifica lo radical. \((x−\frac{1}{2})=\pm\frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}\) Resolver para x. \(x=\frac{1}{2}+\pm\frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}\) Reescribe para mostrar dos soluciones. \(x=\frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}\),\(x=\frac{1}{2}−\frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}\) Cheque. Te dejamos el cheque

Resolver:\((x−\frac{1}{3})^2=\frac{5}{9}\).

- Contestar

-

\(x=\frac{1}{3}+\frac{\sqrt{5}}{3}\),\(x=\frac{1}{3}−\frac{\sqrt{5}}{3}\)

Resolver:\((y−\frac{3}{4})^2=\frac{7}{16}\).

- Contestar

-

\(y=\frac{3}{4}+\frac{\sqrt{7}}{4}\),\(y=\frac{3}{4}−\frac{\sqrt{7}}{4}\),

Comenzaremos la solución al siguiente ejemplo aislando el binomio.

Resolver:\((x−2)^2+3=30\).

- Contestar

-

\((x−2)^2+3=30\) Aislar el término binomial. \((x−2)^2=27\) Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada. \(x−2=\pm\sqrt{27}\) Simplifica lo radical. \(x−2=\pm3\sqrt{3}\) Resolver para x. \(x=2+\pm3\sqrt{3}\) \(x−2=\pm3\sqrt{3}\) \(x=2+3\sqrt{3}\),\(x=2−3\sqrt{3}\) Cheque. Te dejamos el cheque

Resolver:\((a−5)^2+4=24\).

- Contestar

-

\(a=5+2\sqrt{5}\),\(a=5−2\sqrt{5}\)

Resolver:\((b−3)^2−8=24\).

- Contestar

-

\(b=3+4\sqrt{2}\),\(b=3−4\sqrt{2}\)

Resolver:\((3v−7)^2=−12\).

- Contestar

-

\((3v−7)^2=−12\) Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada. \(3v−7=\pm\sqrt{−12}\) El no\(\sqrt{−12}\) es un número real. No hay una solución real.

Resolver:\((3r+4)^2=−8\).

- Contestar

-

ninguna solución real

Los lados izquierdos de las ecuaciones en los siguientes dos ejemplos no parecen ser de la forma\(a(x−h)^2\). Pero son trinomios cuadrados perfectos, así que vamos a factorizarlos para ponerlos en la forma que necesitamos.

Resolver:\(p^2−10p+25=18\).

- Contestar

-

El lado izquierdo de la ecuación es un trinomio cuadrado perfecto. Lo faccionaremos primero.

\(p^2−10p+25=18\) Facturar el trinomio cuadrado perfecto. \((p−5)^2=18\) Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada. \(p−5=\pm\sqrt{18}\) Simplifica lo radical. \(p−5=\pm3\sqrt{2}\) Resolver para p. \(p=5\pm3\sqrt{2}\) Reescribe para mostrar dos soluciones. \(p=5+3\sqrt{2}\),\(p=5−3\sqrt{2}\) Cheque. Te dejamos el cheque.

Resolver:\(x^2−6x+9=12\).

- Contestar

-

\(x=3+2\sqrt{3}\),\(x=3−2\sqrt{3}\)

Resolver:\(y^2+12y+36=32\).

- Contestar

-

\(y=−6+4\sqrt{2}\),\(y=−6−4\sqrt{2}\)

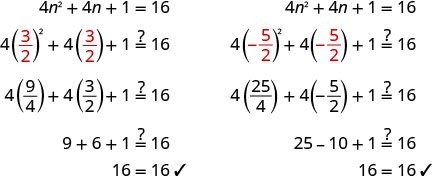

Resolver:\(4n^2+4n+1=16\).

- Contestar

-

Nuevamente, notamos que el lado izquierdo de la ecuación es un trinomio cuadrado perfecto. Lo faccionaremos primero.

\(4n^2+4n+1=16\) Facturar el trinomio cuadrado perfecto. \((2n+1)^2=16\) Utilice la Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada. \((2n+1)=\pm\sqrt{16}\) Simplifica lo radical. \((2n+1)=\pm4\) Resolver para n. \(2n=−1\pm4\) Divide cada lado por 2. \(\frac{2n}{2}=\frac{−1\pm4}{2}\)

\(n=\frac{−1\pm4}{2}\)

Reescribe para mostrar dos soluciones. \(n=\frac{−1+4}{2}\),\(n=\frac{−1−4}{2}\) Simplifica cada ecuación. \(n=\frac{3}{2}\),\(n=−\frac{5}{2}\) Cheque.

Resolver:\(9m^2−12m+4=25\).

- Contestar

-

\(m=\frac{7}{3}\),\(m=−1\)

Resolver:\(16n^2+40n+25=4\).

- Contestar

-

\(n=−\frac{3}{4}\), \(n=−\frac{7}{4}\)

Acceda a estos recursos en línea para obtener instrucción y práctica adicionales con la resolución de ecuaciones cuadráticas:

- Resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas: Resolver tomando raíces cuadradas

- Uso de raíces cuadradas para resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas

- Resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas: El método de raíz cuadrada

Conceptos clave

- Propiedad de raíz cuadrada

Si\(x^2=k\), y\(k\ge 0\), entonces\(x=\sqrt{k}\) o\(x=−\sqrt{k}\).

Glosario

- ecuación cuadrática

- Una ecuación cuadrática es una ecuación de la forma\(ax^2+bx+c=0\) donde\(a \ne 0\).

- Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada

- La Propiedad Raíz Cuadrada establece que, si\(x^2=k\), y\(k\ge 0\), entonces\(x=\sqrt{k}\) o\(x=−\sqrt{k}\).