4.2: Subgrupo Pruebas y Celosías

- Page ID

- 115975

Usando Lemma\(4.1.1\) y el argumento que lo precede, tenemos lo siguiente.

Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Un subconjunto\(H\) de un grupo\(G\) es un subgrupo de\(G\) si y solo si

- \(H\)está cerrado bajo\(G\) operación;

- El elemento de identidad de\(G\) está en\(H\text{;}\) y

- Para\(a\in H\text{,}\)\(a\) la inversa de cada uno\(G\) está contenida en\(H\text{.}\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Para cada uno de los siguientes, probar que el subconjunto dado\(H\) de grupo\(G\) es o no un subgrupo de\(G\text{.}\)

- \(H=3\mathbb{Z}\text{,}\)\(G=\mathbb{Z}\text{.}\)

- \(H=\{0,1,2,3\}\text{,}\)\(G=\mathbb{Z}_6\text{;}\)

- \(H=\mathbb{R}^*\text{,}\)\(G=\mathbb{R}\text{;}\)

- \(H=\{(0,x,y,z):x,y,z\in \mathbb{R}\}\text{,}\)\(G=\mathbb{R}^4\text{.}\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{2}\)

Generalizando la Parte 1 del teorema anterior, tenemos\(n\mathbb{Z}\leq \mathbb{Z}\) para cada\(n\in \mathbb{Z}^+\text{.}\)

La prueba de ello se deja como ejercicio para el lector.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{3}\)

Considere el grupo\(\langle F,+\rangle\text{,}\) donde\(F\) está el conjunto de todas las funciones de\(\mathbb{R}\) a\(\mathbb{R}\) y\(+\) es adición puntual. ¿Cuáles de los siguientes son subgrupos de\(F\text{?}\)

-

\(H=\{f\in F: f(5)=0\}\text{;}\)

-

\(K=\{f\in F: f \text{ is continuous} \}\text{;}\)

-

\(L=\{f\in F: f \text{ is differentiable} \}\text{.}\)

¿Alguno de\(H\text{,}\)\(K\text{,}\) y\(L\) subgrupos el uno del otro?

De hecho, podemos reducir el número de hechos que necesitamos verificar para probar que un subconjunto\(H\subseteq G\) es un subgrupo de\(G\) a solo dos.

Teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\): Two-Step Subgroup Test

Dejar\(G\) ser un grupo y\(H\subseteq G\text{.}\) Entonces\(H\) es un subgrupo de\(G\) si

- \(H\neq \emptyset\text{;}\)y

- Para cada\(a,b\in H\text{,}\)\(ab^{-1}\in H\text{.}\)

- Prueba

-

Supongamos que las dos propiedades anteriores se mantienen. Ya que\(H≠∅\), existe\(x∈G\) tal que\(x∈H\). Entonces\(e_G=xx^{−1}\) está adentro\(H\), por la segunda propiedad. A continuación, por cada que\(a∈H\) tenemos\(a^{−1}=e_Ga^{−1}∈H\) (nuevamente por la segunda propiedad). Por último, si\(a,b∈H\) entonces ya lo hemos mostrado\(b^{−1}∈H\); así\(ab=a(b^{−1})^{−1}∈H\), una vez más por la segunda propiedad. Así,\(H≤G\).

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{4}\)

- Utilice la prueba de subgrupos de dos pasos para demostrar que\(3\mathbb{Z}\) es un subgrupo de\(\mathbb{Z}\text{.}\)

- Utilice la prueba de subgrupos de dos pasos para demostrar que\(SL(n,\mathbb{R})\) es un subgrupo de\(GL(n,\mathbb{R})\text{.}\)

que es sencillo probar el siguiente teorema.

Teorema\(\PageIndex{3}\)

Si\(H\) es un subgrupo de un grupo\(G\) y\(K\) es un subconjunto de\(H\text{,}\) entonces\(K\) es un subgrupo de\(H\) si y solo si es un subgrupo de\(G\text{.}\)

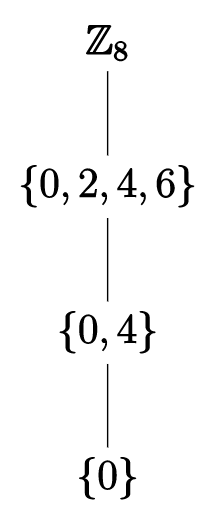

Puede ser útil observar cómo los subgrupos de un grupo se relacionan entre sí. Una forma de hacerlo es considerar las redes de subgrupos (también conocidas como diagramas de subgrupos). Para dibujar una celosía de subgrupo para un grupo\(G\text{,}\) enumeramos todos los subgrupos de\(G\text{,}\) escribir un subgrupo\(K\) debajo de un subgrupo\(H\text{,}\) y conectarlos con una línea, si\(K\) es un subgrupo de\(H\) y no hay un subgrupo apropiado\(L\) de\(H\) que contenga \(K\)como un subgrupo apropiado.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{5}\)

Considerar el grupo\(\mathbb{Z}_8\text{.}\) Veremos más adelante que los subgrupos de\(\mathbb{Z}_8\) son\(\{0\}\text{,}\)\(\{0,2,4,6\}\text{,}\)\(\{0,4\}\) y\(\mathbb{Z}_8\) en sí mismos. Así lo\(\mathbb{Z}_8\) tiene el siguiente subgrupo de celosía.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{6}\)

Refiriéndose al Ejemplo\(4.2.3\), dibujar la porción de la red del subgrupo para\(F\) que muestre las relaciones entre sí mismo y sus subgrupos propios\(H\text{,}\)\(K\text{,}\) y\(L\text{.}\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{7}\)

Indicar las relaciones de subgrupos entre los siguientes grupos:\(\mathbb{Z}\text{,}\)\(12\mathbb{Z}\text{,}\)\(\mathbb{Q}^+\text{,}\)\(\mathbb{R}\text{,}\)\(6\mathbb{Z}\text{,}\)\(\mathbb{R}^+\text{,}\)\(3\mathbb{Z}\text{,}\)\(G=\langle \{\pi^n:n\in \mathbb{Z}\},\cdot\,\rangle\) y\(J=\langle \{6^n:n\in \mathbb{Z}\},\cdot\,\rangle .\)

Terminamos con un teorema sobre homomorfismos y subgrupos que nos lleva a otro grupo invariante.

Teorema\(\PageIndex{4}\)

Dejar\(G\) y\(G'\) ser grupos, dejar\(\phi\) un homomorfismo de\(G\) a\(G'\text{,}\) y dejar que\(H\) un subgrupo de\(G\text{.}\) Entonces\(\phi(H)\) es un subgrupo de\(G'\text{.}\)

- Prueba

-

La prueba se deja como ejercicio para el lector.

Corolario\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Las probabilidades asignadas a eventos por una función de distribución en un espacio muestral están dadas por.

- Prueba

-

Si\(G\simeq G'\) y\(G\) contiene exactamente\(n\) subgrupos (\(n\in \mathbb{Z}^+\)), entonces también lo hace\(G'\text{.}\)

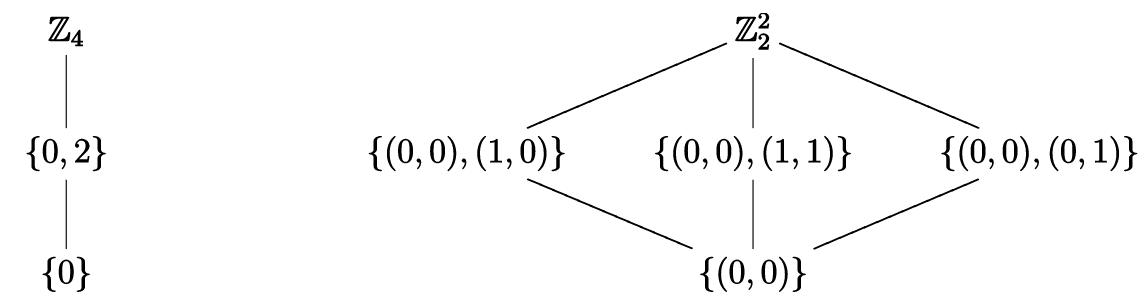

Esta es otra forma de, por ejemplo, distinguir entre los grupos\(\mathbb{Z}_4\) y el grupo Klein 4\(\mathbb{Z}_2^2\text{.}\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{8}\)

Por inspección,\(\mathbb{Z}_4\) y\(\mathbb{Z}_2^2\) tener, respectivamente, las siguientes celosías de subgrupo.

Dado que\(\mathbb{Z}_4\) contiene exactamente\(3\) subgrupos y\(\mathbb{Z}_2^2\) exactamente\(5\), tenemos que\(\mathbb{Z}_4\not\simeq \mathbb{Z}_2^2\text{.}\)