27.1: Complemento ortogonal

- Page ID

- 114988

Un vector\(u\) es ortogonal a un subespacio\(W\) de\(R^n\) si\(u\) es ortogonal a cualquiera\(w\) en\(W\) (\(u \cdot w=0\)para todos\(w \in W\)).

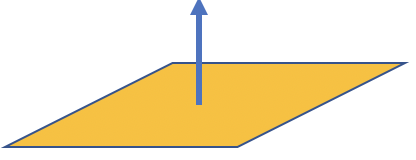

Por ejemplo, consideremos la siguiente figura, si consideramos que el plano es un subespacio entonces el vector perpendicular que sale del plano es ortogonal a cualquier vector del plano:

El complemento ortogonal de\(W\) es el conjunto de todos los vectores que son ortogonales a\(W\). El conjunto se denota como\(W_{\bot}\).

¿Es\(W_{\bot}\) un subespacio de\(R^n\)? Justifica tu respuesta brevemente.

¿Cuáles son los vectores en ambos\(W\) y\(W_{\bot}\)?

Proyección de un vector sobre un subespacio

Pensar que una proyección sobre un subespacio es análoga a una sombra sobre una superficie. Aspectos de un objeto El espacio 3D se representa en una sombra 2D pero no se puede tomar la sombra por sí mismo y recrear exactamente la superficie 3D.

A continuación se presenta la definición matimatical de la proyección sobre un subespacio.

\(W\)Sea un subespacio\(R^n\) de dimensión\(m\). Dejar\(\{w_1,\cdots,w_m\}\) ser una base ortonormal para\(W\). Entonces la proyección del vector\(v\) en\(R^n\) sobre\(W\) se denota como\(\mbox{proj}_Wv\) y se define como\(\mbox{proj}_Wv = (v\cdot w_1)w_1+(v\cdot w_2)w_2+\cdots+(v\cdot w_m)w_m\).

Otra forma de decir la definición anterior es que el proyecto de\(v\) sobre el\(W\) es solo la suma de\(v\) proyectado sobre cada vector en una base de\(W\).

Observaciones:

Recordemos en la conferencia sobre Proyecciones, discutimos la proyección sobre un vector, que es el caso\(m=1\). Se utilizó la proyección para\(m>1\) en el algoritmo Gram-Schmidt.

La proyección no depende de qué base ortonormal elijas.

Si\(v\) está en\(W\), tenemos\(\mbox{proj}_Wv=v\).

El teorema de la descomposición ortogonal

\(W\)Déjese ser un subespacio de\(R^n\). Cada vector in\(v\) in se\(R^n\) puede escribir de forma única en la forma\(v = w+w_{\bot}\), donde\(w\) está adentro\(W\) y\(w_{\bot}\) es ortogonal a\(W\) (es decir,\(w_{\bot}\) está adentro\(W_{\bot}\)). Además,\(w=\mbox{proj}_Wv\) y\(w_{\bot} = v-\mbox{proj}_Wv\).

Dejar\(x\) ser un punto en\(R^n\),\(W\) ser un subespacio de\(R^n\). La distancia de\(x\) a\(W\) se define como la mínima de las distancias desde\(x\) a cualquier punto\(y\) en\(W\). \(d(x,W)=\min \{\|x-y\|: \mbox{ for all }y \mbox{ in } W\}\). El óptimo se\(y\) puede lograr en\(\mbox{proj}_Wx\), y\(d(x,W)=|x-\mbox{proj}_Wx|\).

Let\(v=(3,2,6)\) y\(W\) es el subespacio que consiste en todos los vectores con la forma\((a,b,b)\). Encuentra la proyección de\(v\) sobre\(W\).

Let\(v=(3,2,6)\) y\(W\) es el subespacio que consiste en todos los vectores con la forma\((a,b,b)\). Encuentra la distancia de\(v\) a\(W\).