3.9: Proyecciones Fischer y Haworth

- Page ID

- 2331

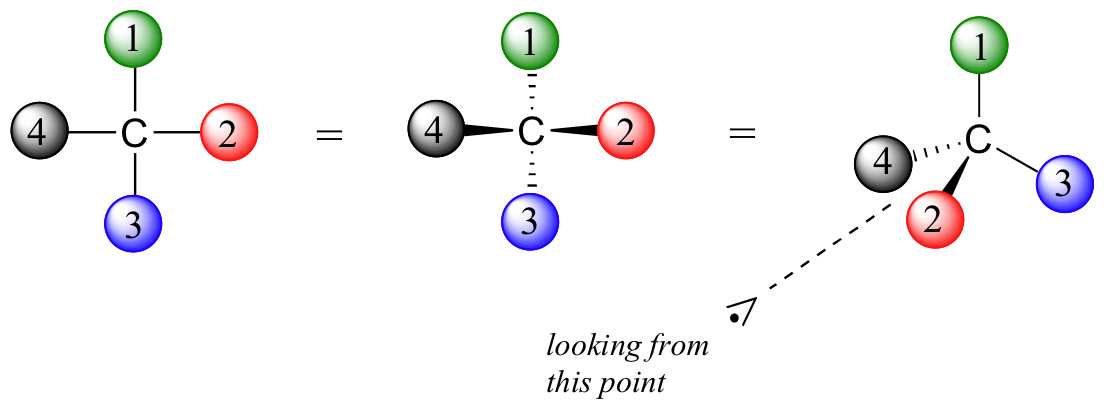

Cuando se lee literatura química y bioquímica, es posible que encuentre diferentes convenciones para dibujar moléculas en tres dimensiones, depende en el contexto de la discusión. Mientras químicos orgánicos prefieren usar la convención de líneas continuas y descontinuas para representar estereoquímica, bioquímicos seguido usan proyecciones llamadas Fischer y Haworth para discutir y comparar la estructura de azucares.

Proyecciones Fisher muestran azucares en sus posiciones de silla abierta. En una proyección Fischer, el átomo de carbón de una molécula de azúcar esta conectada verticalmente por líneas solidas, mientras enlaces de carbón-oxigeno y carbón-hidrogeno son mostradas horizontalmente. Información estereoquímica es seguida por una regla simple: enlaces verticales van dentro de el plano de la pagina, mientras enlaces horizontales van afuera de el plano de la pagina.

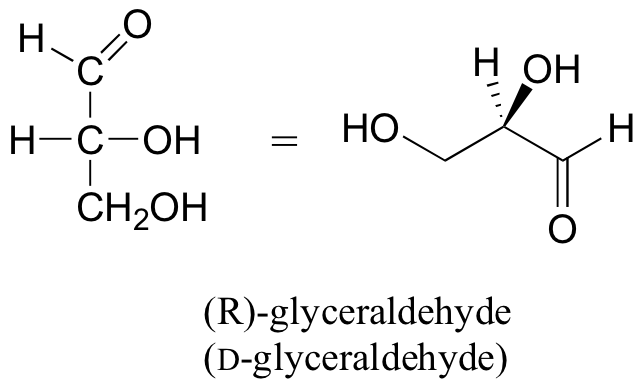

En seguida hay dos representaciones diferentes de (R)- gliceraldehído, la molecula de azúcar mas pequeña (también llamada D- gliceraldehído en la nomenclatura estereoquímica usada por bioquímicos)

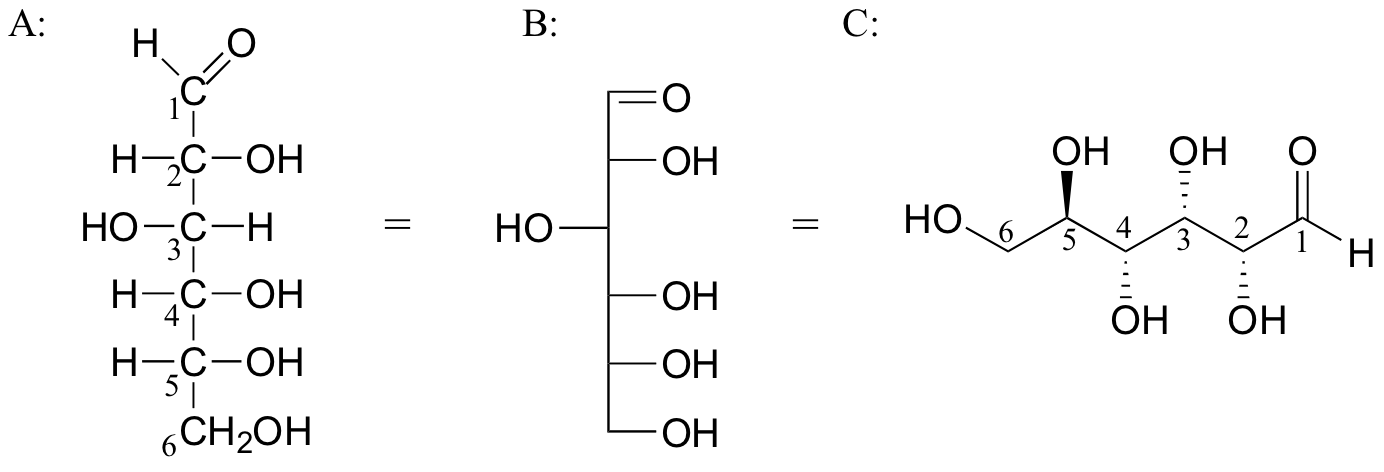

Abajo hay tres representaciones de la forma abierta de D-glucosa: en la proyección Fischer (A), in la “estructura linear” variaciones de la proyección Fisher en la cual carbón y hidrogeno no son mostrados, y finalmente en el estilo “zigzag” (C) la cual los químicos orgánicos prefieren.

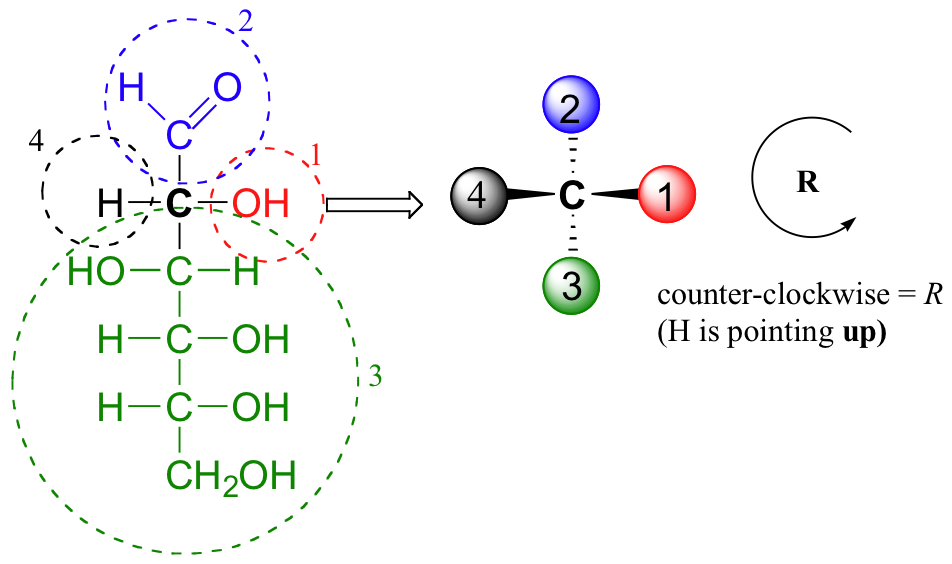

Cuando se ‘traduce’ proyecciones Fischer a ‘zigzag’ hay que tener cuidado – es muy fácil equivocarse en la estereoquímica. Probablemente la mejor manera de convertirlos es asignar las configuraciones R/S, y proceder de allí. Para decidir si el estereocentro es R o S en la proyección Fischer , note que el hidrogeno, en un enlace horizontal, esta dirigido hacia ti – por lo tanto, un circulo en contra del reloj significa R, y una rotación con el reloj significa S (lo opuesto cuando el hidrogeno esta alejándose de usted).

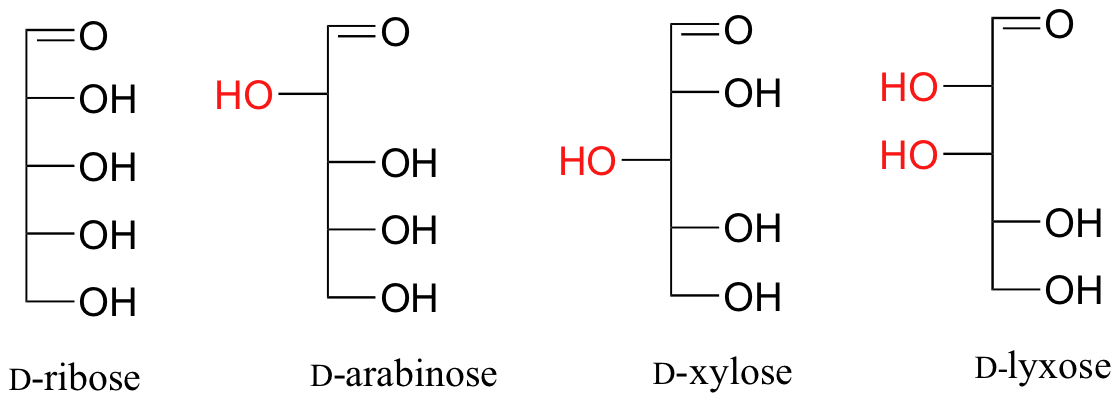

Proyecciones Fischer son útiles cuando se estas viendo diferentes estructuras de azucares diastereoméricas, porque de esta manera uno puede notar las diferencias estereoquímicas basado en que si el grupo hidroxilo esta en la derecha u izquierda.

Ejemplo 3.15

Dibuja estructuras ‘zigzag’ (usando la convención solida/decaída para mostrar estereoquímica) para las cuatro azucares de arriba. Nombra todas los estereocentro como R o S.

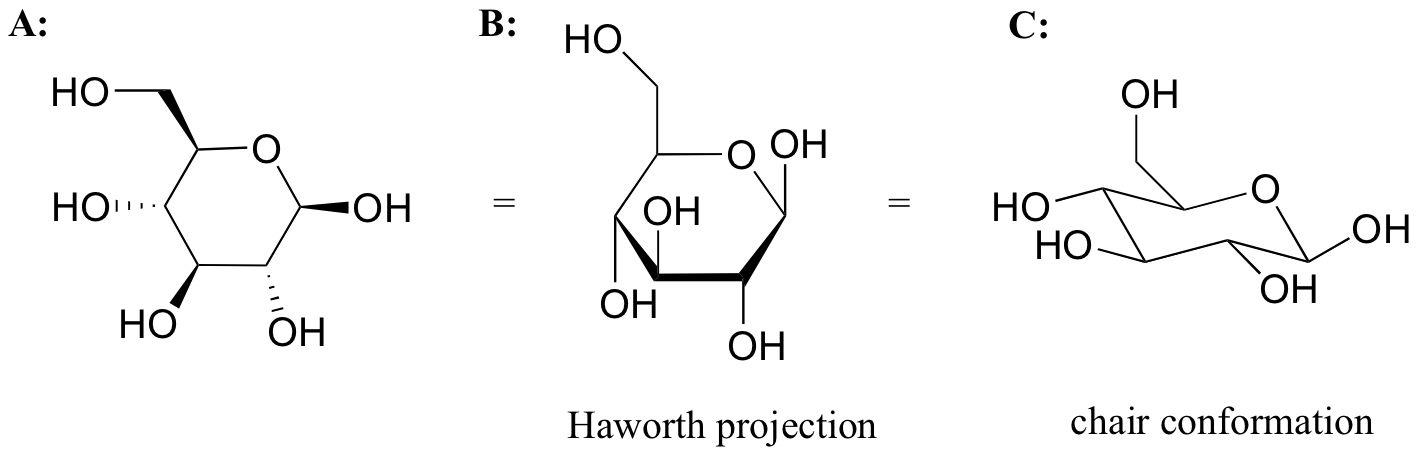

Mientras proyecciones Fischer son usadas para la posición de silla abierta, proyecciones Haworth son usadas para ver azucares en su forma cíclica. El diastereómero beta de la forma cíclica de glucosa es mostrada abajo en tres diferentes representaciones, con la proyección Haworth en el medio.

A pesar que la proyección Haworth es una manera conveniente de mostrar estereoquímica, no provee una representación de la confirmación. Para mostrar ambos, configuración y estereoquímica, debe de dibujar el anillo en la configuración de silla, como la figura C de arriba.