5.4: La base de las diferencias en el desplazamiento químico

- Page ID

- 2345

5.4A: Protección y deshielding diamagnético Diamagnetic shielding and deshielding

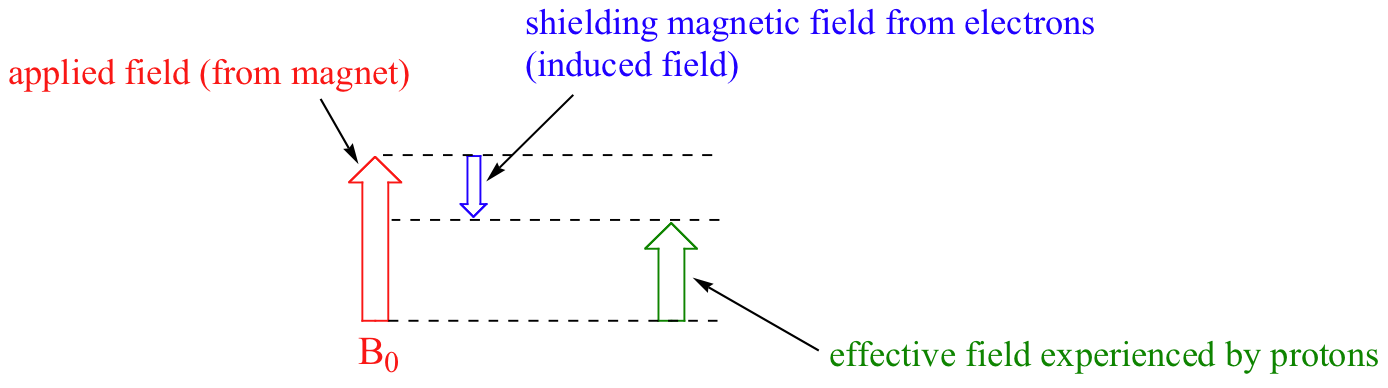

Pasamos ahora a la pregunta de por qué los protones no equivalentes tienen diferentes cambios químicos. El cambio químico de un protón dado se determina principalmente por su entorno electrónico inmediato. Consideremos la molécula de metano (CH4), en la que los protones tienen un desplazamiento químico de 0,23 ppm. Los electrones de valencia alrededor del carbono de metilo, cuando son sometidos a B0, son inducidos a circular y por lo tanto generan su propio campo magnético muy pequeño que se opone a B0. Este campo inducido, en un grado pequeño pero significativo, escuda a los protones cercanos de experimentar toda la fuerza de B0, un efecto conocido como blindaje diamagnético local. Por lo tanto, los protones de metano no experimentan toda la fuerza de B0 - Lo que experimentan se llama Beff, o el campo efectivo, que es ligeramente más débil que B0.

Por lo tanto, su frecuencia de resonancia es ligeramente inferior a lo que sería si no tuvieran electrones cerca para protegerlos

Ahora considere el fluoruro de metilo, CH3F, en el que los protones tienen un desplazamiento químico de 4,26 ppm, significativamente mayor que el del metano. Esto es causado por algo llamado el efecto pantalla. Debido a que el flúor es más electronegativo que el carbono, retira los electrones de valencia del carbono, disminuyendo efectivamente la densidad electrónica alrededor de cada uno de los protones. Para los protones, menor densidad electrónica significa menos blindaje diamagnético, lo que significa una mayor exposición general a B0, un Beff más fuerte, y una frecuencia de resonancia mayor. Dicho de otra manera, el flúor,

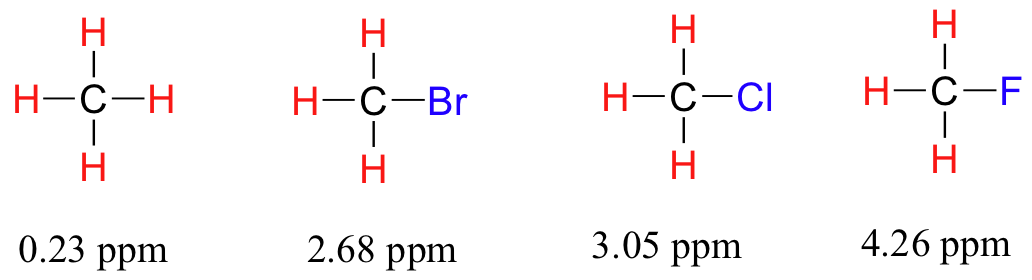

Now consider methyl fluoride, CH3F, in which the protons have a chemical shift of 4.26 ppm, significantly higher than that of methane. This is caused by something called the deshielding effect. Because fluorine is more electronegative than carbon, it pulls valence electrons away from the carbon, effectively decreasing the electron density around each of the protons. For the protons, lower electron density means less diamagnetic shielding, which in turn means a greater overall exposure to B0, a stronger Beff, and a higher resonance frequency. Put another way, the fluorine, by pulling electron density away from the protons, is deshielding them, leaving them more exposed to B0. As the electronegativity of the substituent increases, so does the extent of deshielding, and so does the chemical shift. This is evident when we look at the chemical shifts of methane and three halomethane compounds (remember that electronegativity increases as we move up a column in the periodic table).

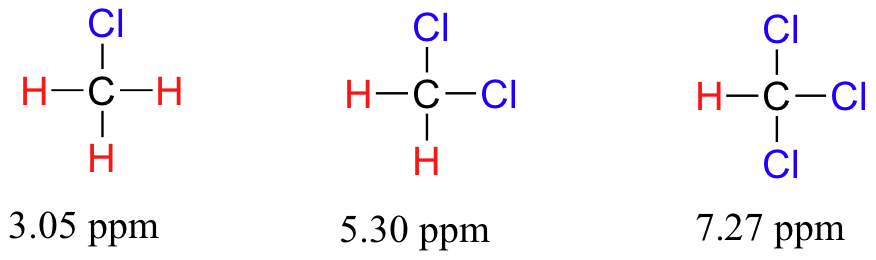

A un grado mayor, entonces, podemos predecir tendencias en el cambio químico considerando cuánto effecto pantalla está ocurriendo cerca de un protón. El cambio químico del triclorometano es, como se esperaba, mayor que el del diclorometano, que a su vez es mayor que el del clorometano.

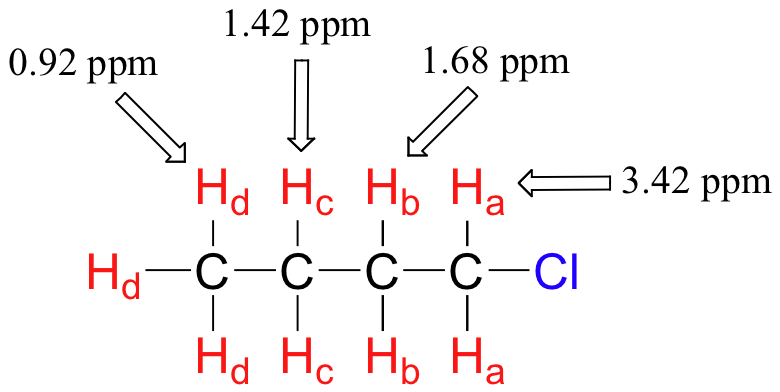

El efecto pantalla de un substituto electronegativo disminuye agudamente con el aumento de la distancia:

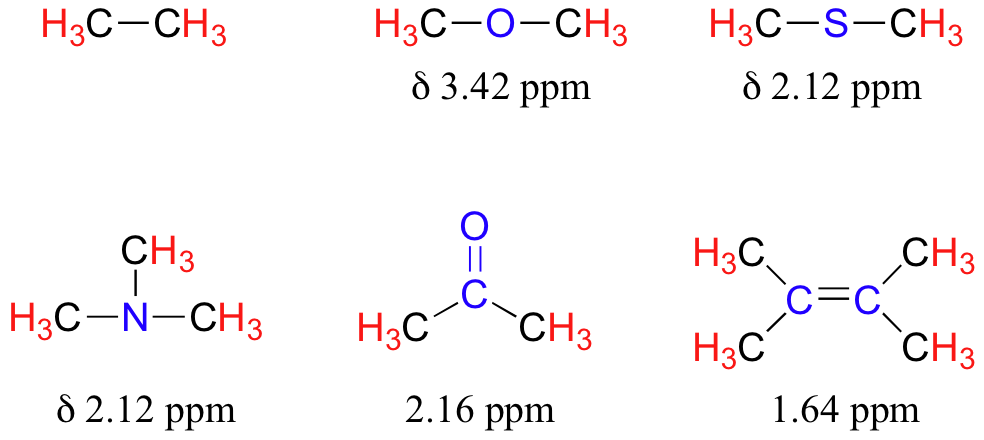

The presence of an electronegative oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, or sp2-hybridized carbon also tends to shift the NMR signals of nearby protons slightly downfield:

Table 2 lists typical chemical shift values for protons in different chemical environments.

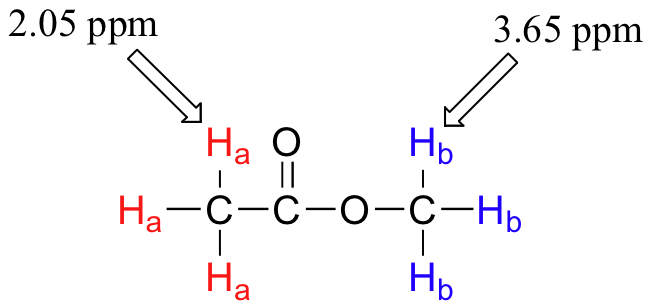

Armed with this information, we can finally assign the two peaks in the the 1H-NMR spectrum of methyl acetate that we saw a few pages back. The signal at 3.65 ppm corresponds to the methyl ester protons (Hb), which are deshielded by the adjacent oxygen atom. The upfield signal at 2.05 ppm corresponds to the acetate protons (Ha), which is deshielded - but to a lesser extent - by the adjacent carbonyl group.

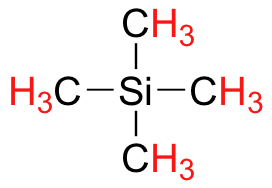

Finally, a note on the use of TMS as a standard in NMR spectroscopy: one of the main reasons why the TMS proton signal was chosen as a zero-point is that the TMS protons are highly shielded: silicon is slightly less electronegative than carbon, and therefore donates some additional shielding electron density. Very few organic molecules contain protons with chemical shifts that are negative relative to TMS.

5.4B: The chemical shifts of aromatic and vinylic protons

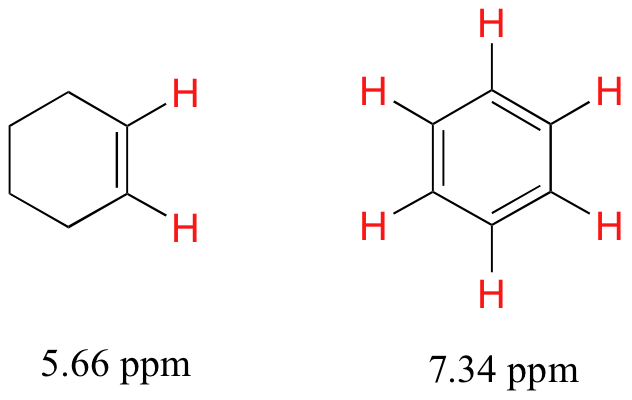

Some protons resonate much further downfield than can be accounted for simply by the deshielding effect of nearby electronegative atoms. Vinylic protons (those directly bonded to an alkene carbon) and aromatic (benzylic) protons are dramatic examples.

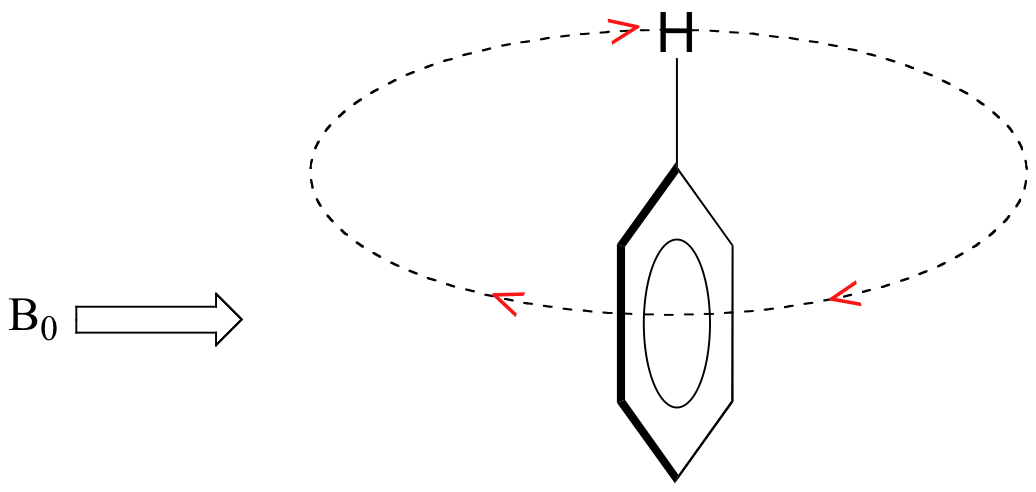

We'll consider the aromatic proton first. Recall that in benzene and many other aromatic structures, a sextet of pelectrons is delocalized around the ring. When the molecule is exposed to B0, these pelectrons begin to circulate in a ring current, generating their own induced magnetic field that opposes B0. In this case, however, the induced field of the pelectrons does not shield the benzylic protons from B0 as you might expect– rather, it causes the protons to experience a stronger magnetic field in the direction of B0 – in other words, it adds to B0 rather than subtracting from it.

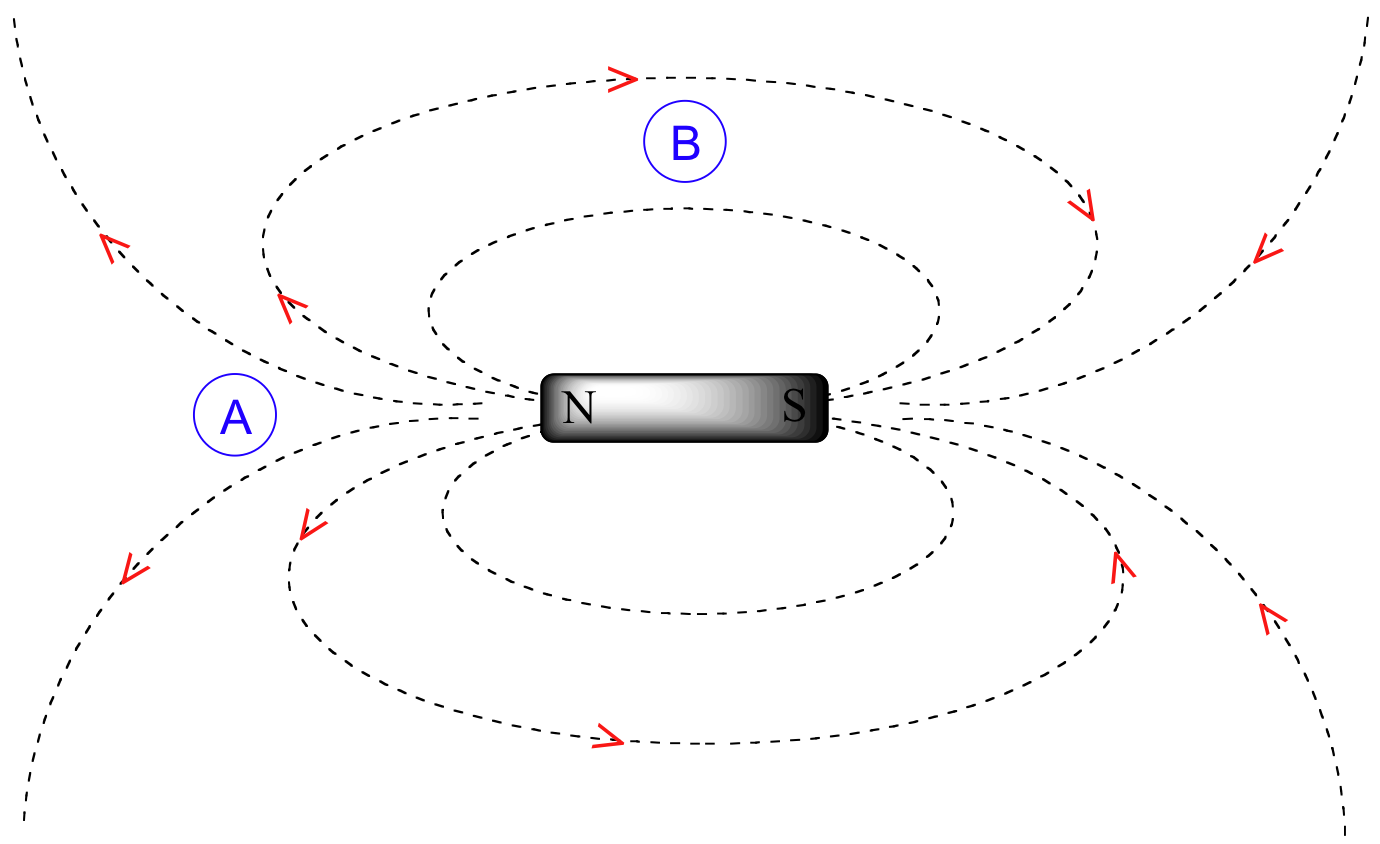

To understand how this happens, we need to understand the concept of diamagnetic anisotropy (anisotropy means `non-uniformity`). So far, we have been picturing magnetic fields as being oriented in a uniform direction. This is only true over a small area. If we step back and take a wider view, however, we see that the lines of force in a magnetic field are actually anisotropic. They start in the 'north' direction, then loop around like a snake biting its own tail.

If we are at point A in the figure above, we feel a magnetic field pointing in a northerly direction. If we are at point B, however, we feel a field pointing to the south.

In the induced field generated by the aromatic ring current, the benzylic protons are at the equivalent of ‘point B’ – this means that the induced current in this region of space is oriented in the same direction as B0.

In total, the benzylic protons are subjected to three magnetic fields: the applied field (B0) and the induced field from the pelectrons pointing in one direction, and the induced field of the non-aromatic electrons pointing in the opposite (shielding) direction. The end result is that benzylic protons, due to the anisotropy of the induced field generated by the pring current, appear to be highly deshielded. Their chemical shift is far downfield, in the 6.5-8 ppm region.

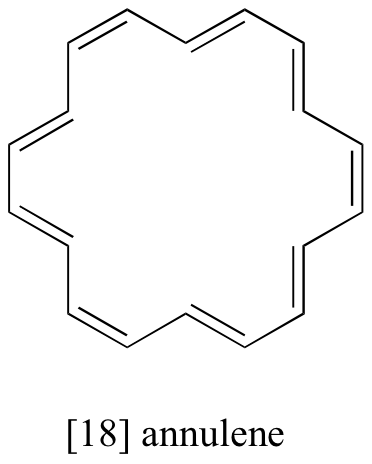

Exercise 5.5: The 1H-NMR spectrum of [18] annulene has two peaks, at 8.9 ppm and -1.8 ppm (upfield of TMS!) with an integration ratio of 2:1. Explain the unusual chemical shift of the latter peak.

Diamagnetic anisotropy is also responsible for the downfield chemical shifts of vinylic protons and aldehyde protons (4.5-6.5 ppm and 9-10 ppm, respectively). These groups are not aromatic and thus do not generate ring currents as does benzene, but the pelectrons circulate in such a way as to generate a magnetic field that adds to B0in the regions of space occupied by the protons.

5.4C: Hydrogen-bonded protons

Protons that are directly bonded to oxygen and nitrogen have chemical shifts that can vary widely depending on solvent and concentration. This is because these protons can participate to varying degrees in hydrogen-bonding interactions, and hydrogen bonding greatly influences the electron density around the proton. Signals for hydrogen-bonding protons also tend to be broader than those of hydrogens bonded to carbon, a phenomenon that is also due to hydrogen bonding.