2.4: Ejemplo- Respuesta de segundo orden para un sistema de tres niveles

- Page ID

- 73713

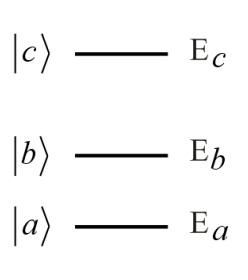

La respuesta de segundo orden es el caso no lineal más simple, pero en la espectroscopia molecular se usa menos comúnmente que las mediciones de tercer orden. La generación de señal requiere una falta de simetría de inversión, lo que la hace útil para estudios de interfaces y sistemas quirales. Sin embargo, mostremos cómo se evaluaría diagramáticamente la respuesta de segundo orden para un sistema muy específico que se muestra a continuación.

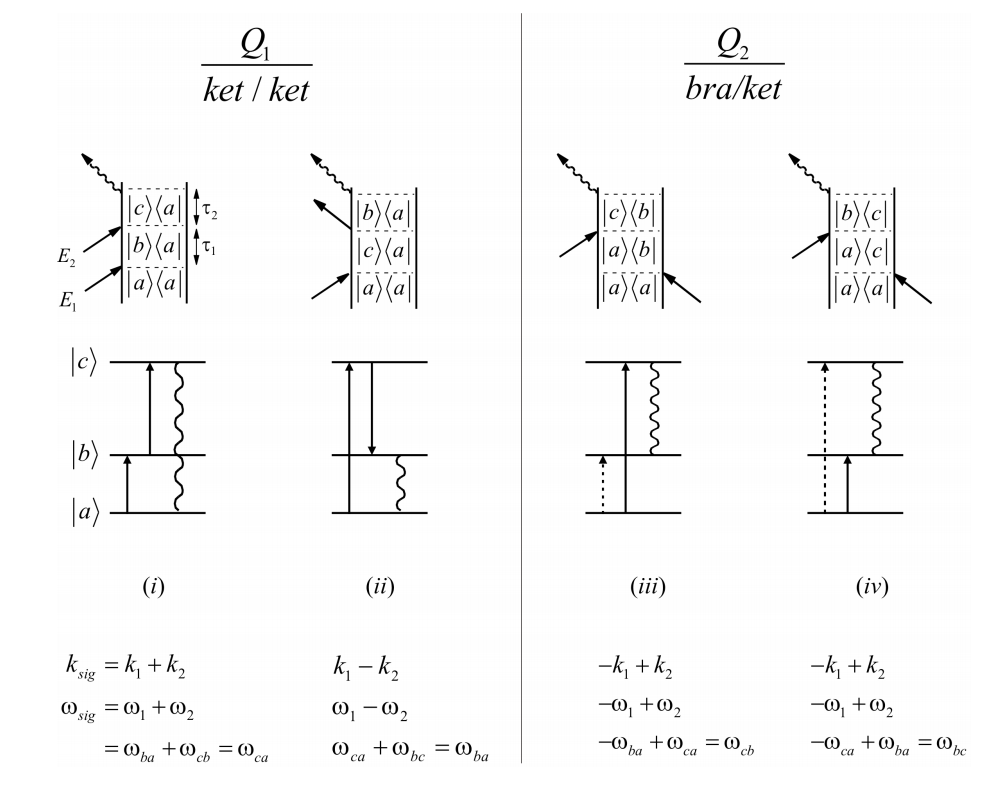

Si solo tenemos población en el estado fundamental en equilibrio y si solo se permiten interacciones resonantes, las permutaciones de diagramas únicos son las siguientes:

A partir de las condiciones de conservación de frecuencia, debe quedar claro que el proceso i es una señal de suma-frecuencia para los campos incidentes, mientras que los diagramas ii - iv se refieren a esquemas de frecuencia de diferencia. Para interpretar mejor a qué se refieren estos diagramas veamos iii. Leyendo de manera ordenada por tiempo, podemos escribir la función de correlación correspondiente a este diagrama como

\[\begin{aligned} C_{2} &=\operatorname{Tr}\left[\mu(\tau) \rho_{e q} \mu(0)\right] \\[4pt] &=(-1)^{1} \mu_{b c} \hat{G}_{c b}\left(\tau_{2}\right) \mu_{c a} \hat{G}_{a b}\left(\tau_{1}\right) \rho_{a a} \mu_{b a}^{*} \\[4pt] &=-p_{a} \mu_{a b} \mu_{b c} \mu_{c a} e^{-i \omega_{a b} \tau_{1}-\Gamma_{a b} \tau_{1}} e^{-i \omega_{c b} \tau_{2}-\Gamma_{c b} \tau_{2}} \end{aligned} \label{3.4.1}\]

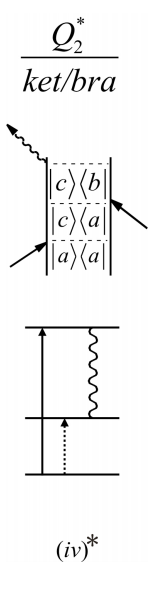

Tenga en cuenta que una interpretación literal de la traza final en el diagrama iv implicaría un evento de absorción, una transición ascendente de b a c. ¿Qué tiene que ver esto con irradiar una señal? Por un lado es importante recordar que un diagrama es solo una taquigrafía matemática, y que no se puede distinguir la absorción y la emisión en la acción final del operador dipolo antes de realizar una traza. La otra cosa a recordar es que un diagrama de este tipo siempre tiene un conjugado complejo asociado a él en la función de respuesta. El complejo conjugado de iv, un término\(Q_2^*\) ket/bra, que se muestra a continuación tiene una transición descendente —emisión— como interacción final. La combinación\(Q_2 − Q_2^*\) finalmente describe lo observable.

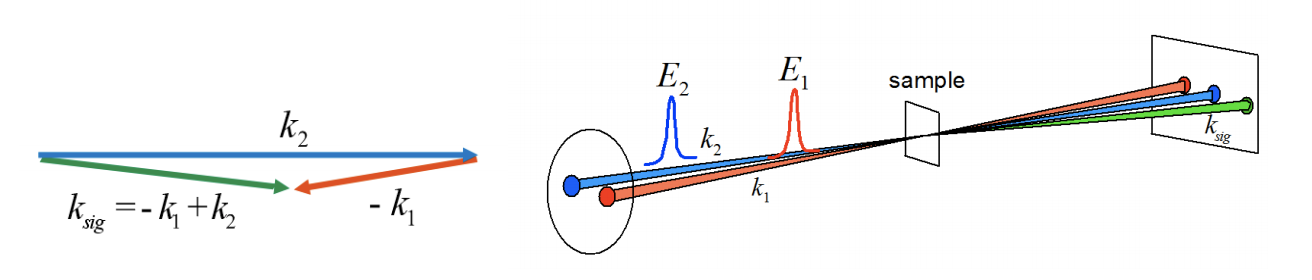

Ahora, considere las condiciones de coincidencia del evector de onda para la señal de segundo orden iii. Recordando que la magnitud del vector de ondas es\(|\bar k| = \omega/c = 2\pi / \lambda\), la longitud de los vectores será escalada por las frecuencias de resonancia. Cuando los dos campos incidentes se cruzan como un ligero ángulo, la señal se emparejaría en fase de tal manera que la señal se radiara más cerca del haz 2. Tenga en cuenta que la coincidencia de ondas más eficiente aquí sería cuando los campos 1 y 2 son colineales.