7.14: Reproducción de bacterias

- Page ID

- 108617

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

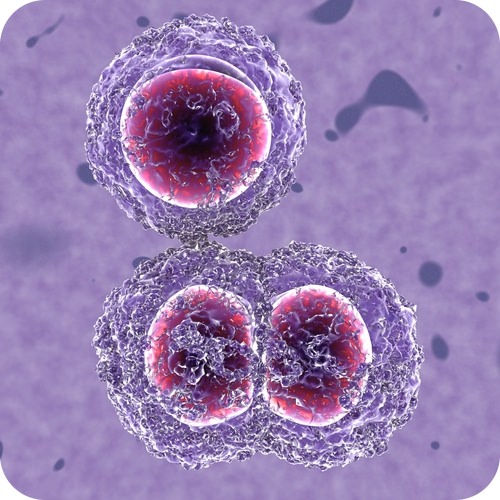

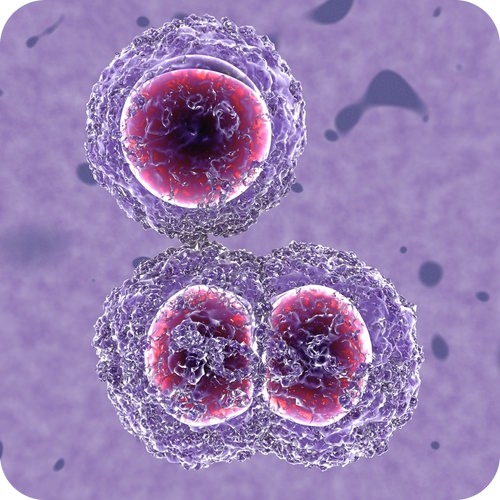

¿Cómo se reproducen las bacterias?

Esencialmente, crecen y se dividen. Mostrar aquí un ejemplo de bacterias Staphylococcus aureus resistentes a meticilina, o MRSA. Observe cómo una bacteria se está dividiendo en dos.

Reproducción en Procariotas

A diferencia de los organismos multicelulares, los aumentos en el tamaño de los procariotas (crecimiento celular) y su reproducción por división celular están estrechamente vinculados. Los procariotas crecen a un tamaño fijo y luego se reproducen a través de la fisión binaria.

Fsión binaria

La fisión binaria es un tipo de reproducción asexual. Ocurre cuando una celda padre se divide en dos celdas hijas idénticas. Esto puede resultar en un crecimiento demográfico muy rápido. Por ejemplo, en condiciones ideales, las poblaciones bacterianas pueden duplicarse cada 20 minutos. Este rápido crecimiento poblacional es una adaptación a un ambiente inestable. ¿Puedes explicar por qué?

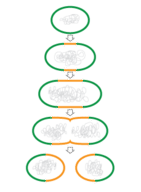

Diagrama esquemático de crecimiento celular (elongación) y fisión binaria de bacilos. Las líneas azules y rojas indican pared celular bacteriana antigua y recién sintetizada, respectivamente. Se copia el ADN dentro de la bacteria y las células hijas reciben una copia exacta del ADN parental. La fisión involucra una proteína citoesquelética FtsZ que forma un anillo en el sitio de división celular.

Diagrama esquemático de crecimiento celular (elongación) y fisión binaria de bacilos. Las líneas azules y rojas indican pared celular bacteriana antigua y recién sintetizada, respectivamente. Se copia el ADN dentro de la bacteria y las células hijas reciben una copia exacta del ADN parental. La fisión involucra una proteína citoesquelética FtsZ que forma un anillo en el sitio de división celular. Transferencia Genética

En la reproducción asexual, todas las crías son exactamente iguales. Este es el mayor inconveniente de este tipo de reproducción. ¿Por qué? La falta de variación genética aumenta el riesgo de extinción. Sin variedad, puede que no haya organismos que puedan sobrevivir a un cambio importante en el medio ambiente.

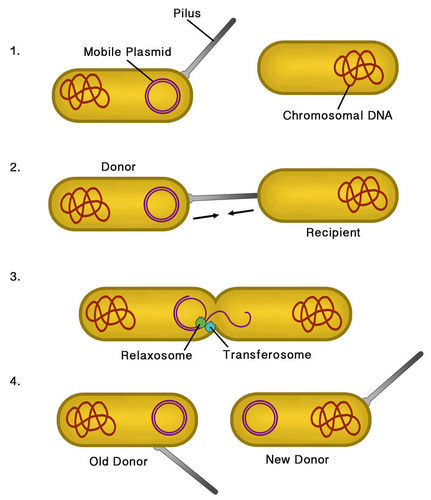

Los procariotas tienen una forma diferente de aumentar la variación genética. Se llama transferencia genética o conjugación bacteriana. Puede ocurrir de dos maneras. Una forma es cuando las células “agarran” trozos de ADN extraviados de su entorno. La otra forma es cuando las células intercambian directamente ADN (generalmente plásmidos) con otras células. Por ejemplo, como se muestra en la Figura a continuación, la célula donante fabrica una estructura llamada F pilus, o pilus sexual. El pilus F une una célula a otra célula. Las membranas de las dos células se fusionan y el material genético, generalmente un plásmido, se mueve hacia la célula receptora. La transferencia genética hace que las bacterias sean muy útiles en biotecnología. Se puede utilizar para crear células bacterianas que porten nuevos genes.

Un diagrama de flujo que muestra conjugación bacteriana. La célula donante forma una estructura llamada F pilus, o pilus sexual. El pilus F une una célula a otra célula. Las membranas de las dos células se fusionan y el material genético, generalmente un plásmido, se mueve hacia la célula receptora.

Un diagrama de flujo que muestra conjugación bacteriana. La célula donante forma una estructura llamada F pilus, o pilus sexual. El pilus F une una célula a otra célula. Las membranas de las dos células se fusionan y el material genético, generalmente un plásmido, se mueve hacia la célula receptora. Resumen

- Las células procariotas crecen hasta cierto tamaño. Entonces se dividen por fisión binaria. Se trata de un tipo de reproducción asexual.

- La fisión binaria produce descendencia genéticamente idéntica.

- La transferencia genética aumenta la variación genética en procariotas.

Revisar

- Describir la fisión binaria.

- ¿Por qué la transferencia genética podría ser importante para la supervivencia de especies procariotas?

- En condiciones ideales, en 2 horas ¿cuántas bacterias pueden resultar de una sola bacteria? ¿5 horas?

| Imagen | Referencia | Atribuciones |

|

[Figura 1] | Licencia: CC BY-NC |

|

[Figura 2] | Crédito: Zachary Wilson Fuente: Fundación CK-12 Licencia: CC BY-NC 3.0 |

|

[Figura 3] | Crédito: Laura Guerin Fuente: Fundación CK-12 Licencia: CC BY-NC 3.0 |