4.1: Introducción

- Page ID

- 127943

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Newton y sus leyes

Hay tres leyes del movimiento que describen la relación entre fuerzas, masa y aceleración.

objetivos de aprendizaje

- Aplicar tres leyes del movimiento de Newton para relacionar fuerzas, masa y aceleración

Las leyes del movimiento de Newton describen la relación entre las fuerzas que actúan sobre un cuerpo y su movimiento debido a esas fuerzas. Por ejemplo, si tu auto se descompone y necesitas empujarlo, debes ejercer una fuerza con las manos sobre el auto para que se mueva. Las leyes del movimiento te dirán qué tan rápido se moverá el auto de tu empuje. Hay tres leyes de movimiento:

Primera ley: Si un objeto no experimenta fuerza neta, entonces su velocidad es constante: el objeto está en reposo (si su velocidad es cero), o se mueve en línea recta con velocidad constante (si su velocidad es distinta de cero). Por ejemplo, si no empujas el auto (sin fuerza), entonces no se mueve.

Segunda ley: La aceleración aa de un cuerpo es paralela y directamente proporcional a la fuerza neta\(\mathrm{F}\) que actúa sobre el cuerpo, está en la dirección de la fuerza neta, y es inversamente proporcional a la masa mm del cuerpo:

\[\mathrm{F=m⋅a \text{ or } a=\dfrac{F}{m}}\]

Por ejemplo, si empujas el auto con mayor fuerza se acelerará más. Pero, si el auto es más masivo (mm es más grande) entonces no acelerará tanto de la misma fuerza de tamaño que un automóvil más ligero.

Tercera ley: Cuando un primer cuerpo ejerce una fuerza\(\mathrm{F_1}\) sobre un segundo cuerpo, el segundo cuerpo ejerce simultáneamente una fuerza\(\mathrm{F_2=−F_1}\) sobre el primer cuerpo. Esto significa que\(\mathrm{F_1}\) y\(\mathrm{F_2}\) son iguales en magnitud y opuestos en dirección. Por ejemplo, cuando empujas un auto, si te está ejerciendo la misma fuerza que estás ejerciendo sobre él, tal vez te preguntes ¿por qué no te mueves hacia atrás? La respuesta es que también hay fuerzas del suelo en tus pies empujándote hacia adelante. Entonces, de hecho, el auto te está empujando una fuerza que es de la misma magnitud que estás usando para empujarlo hacia adelante.

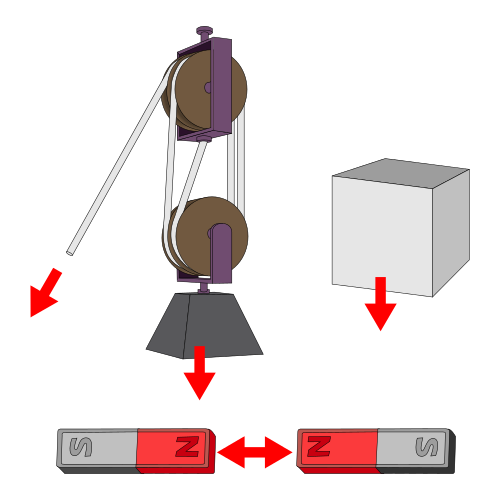

En la siguiente figura hay algunos ejemplos prácticos que ilustran el concepto de fuerza:

- Cepa: mediante el uso de una máquina conocida como polea se puede subir o bajar fácilmente un cuerpo masivo

- Fuerza Gravitacional: un cuerpo masivo es atraído hacia abajo por la fuerza gravitacional practicada por la Tierra

- Fuerza magnética: dos imanes se repelen entre sí cuando los mismos polos se acercan

Ejemplos de Fuerza: Algunas situaciones en las que las fuerzas están en juego.

Puntos Clave

- La aceleración de un objeto es proporcional a la fuerza sobre él.

- La fuerza hace que un objeto se mueva.

- Los objetos con más masa requieren más fuerza para moverse.

Términos Clave

- fuerza: Cualquier influencia que haga que un objeto sufra un cierto cambio, ya sea en lo que respecta a su movimiento, dirección o construcción geométrica.

LICENCIAS Y ATRIBUCIONES

CONTENIDO CON LICENCIA CC, COMPARTIDO PREVIAMENTE

- Curación y Revisión. Proporcionado por: Boundless.com. Licencia: CC BY-SA: Atribución-CompartirIgual

CC CONTENIDO LICENCIADO, ATRIBUCIÓN ESPECÍFICA

- Las leyes del movimiento de Newton. Proporcionado por: Wikipedia. Ubicado en: es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newton's_laws_of_motion. Licencia: CC BY-SA: Atribución-CompartirIgual

- fuerza. Proporcionado por: Wikcionario. Ubicado en: es.wiktionary.org/wiki/force. Licencia: CC BY-SA: Atribución-CompartirIgual

- Archivo:Fuerza examples.svg - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre. Proporcionado por: Wikipedia. Ubicado en: es.wikipedia.org/w/index. php*title=file:force_examples.svg&page=1. Licencia: CC BY-SA: Atribución-CompartirIgual