14.6: Superposición de ondas e interferencia

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

En esta sección, consideramos lo que sucede cuando dos (o más) ondas diferentes se propagan en un medio e interfieren entre sí. El principio de superposición establece que siD1(x,t),D2(x,t), etc, son funciones que satisfacen la ecuación de onda, entonces cualquier combinación lineal de estas funciones,D(x,t): tambiénD(x,t)=a1D1(x,t)+a2D2(x,t)+a3D3(x,t)+… satisfará la ecuación de onda.

Supongamos que sostienes un extremo de una cuerda y la sacudes con una frecuencia específica, creando ondas que son descritas por:D1(x,t)=A1sin(k1x−ω1t+ϕ1) Tu amigo, en el otro extremo de la cuerda sacude la cuerda con una frecuencia diferente, creando ondas que se propagan en sentido contrario y que son descritas por:D2(x,t)=A2sin(k2x+ω2t+ϕ2) La principio de superposición establece que el desplazamiento neto en cualquier posiciónx en algún momento set puede encontrar sumando el desplazamiento de las dos ondas juntas:D(x,t)=A1sin(k1x−ω1t+ϕ1)+A2sin(k2x+ω2t+ϕ2)

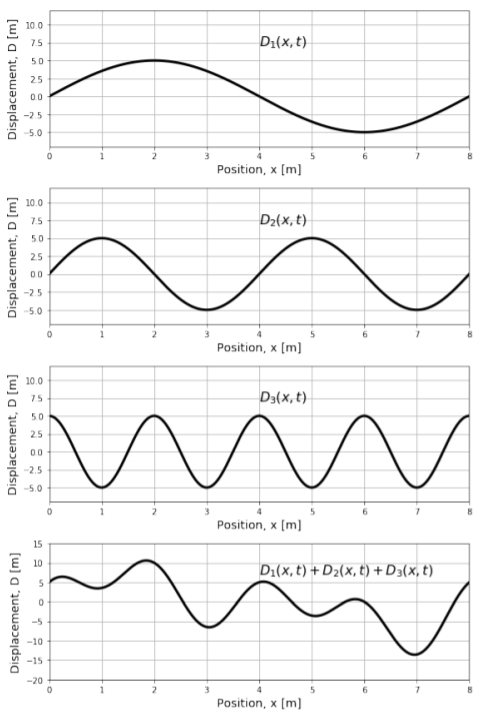

La superposición de ondas se ilustra en la Figura14.6.1, que muestra tres ondas, y su suma resultante en el panel más inferior.

La onda resultante es creada por la “interferencia” de las tres ondas, y matemáticamente es simplemente una suma de las tres ondas individuales en cada posición (e instante en el tiempo). La onda resultante en este ejemplo tiene una forma bastante complicada, que ya no es descrita por una función sinusoidal. Sin embargo, por el principio de superposición, es una solución válida a la ecuación de onda 1.

Las ondas individuales en los tres paneles superiores de la Figura tienen14.6.1 todas una amplitud de5m. La onda resultante, en algunos puntos (por ejemplo, atx=2m), tiene una amplitud que es mayor que cualquiera de las ondas individuales; decimos que, en esas posiciones, las ondas individuales han “interferido constructivamente”. En otras ubicaciones (por ejemplo, atx=6m), la onda resultante tiene una amplitud menor que las ondas individuales, y decimos que las ondas individuales han “interferido destructivamente”. La interferencia entre las olas se puede observar fácilmente en la superficie del agua, por ejemplo, observando el patrón de interferencia constructivo y destructivo de las olas que se originan a partir de dos guijarros que se caen al mismo tiempo a cierta distancia. También se cree que la interferencia constructiva entre las olas está detrás de algunos reportes de olas gigantescas observadas en el mar.

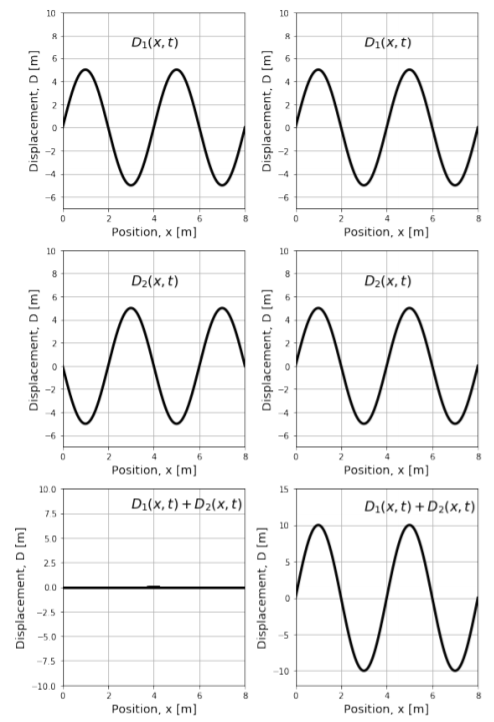

Si dos ondas tienen la misma longitud de onda y amplitud, es posible que interfieran completamente destructivamente, resultando en ninguna onda neta. De igual manera, también pueden interferir completamente constructivamente, dando como resultado una onda con una amplitud mayor. Las interferencias destructivas y constructivas completas se ilustran en el panel izquierdo y derecho de la Figura14.6.2, respectivamente.

Notas al pie

1. El teorema de Fourier establece que cualquier función periódica puede describirse como la combinación lineal de funciones sinusoidales (o coseno). Esta es la razón por la que nos enfocamos en usar una función sinusoidal para describir una onda.