5.10: Detalle- Seguro de Vida

- Page ID

- 82111

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Un ejemplo de estadística y probabilidad en la vida cotidiana es su uso en seguros de vida. Consideramos aquí solo el seguro a plazo de un año (las compañías de seguros son muy creativas en la comercialización de pólizas más complejas que combinan aspectos de seguros, ahorros, inversión, ingresos de jubilación y minimización de impuestos).

Al contratar una póliza de seguro de vida, pagas una prima de tantos dólares y, si mueres durante el año, a tus beneficiarios se les paga una cantidad mucho mayor. El seguro de vida puede pensarse de muchas maneras.

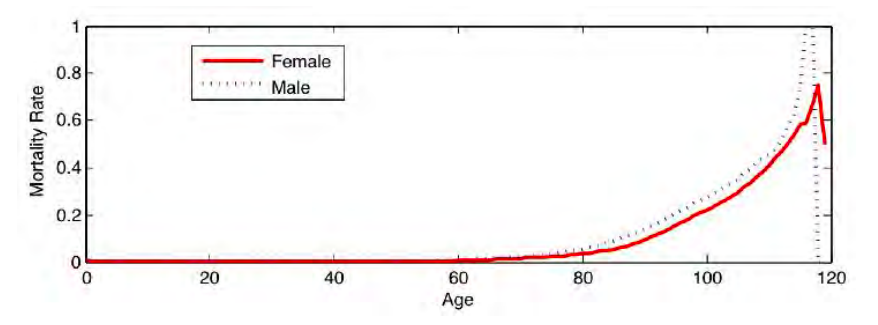

Desde la perspectiva de un jugador, estás apostando a que morirás y la compañía de seguros está apostando a que vivirás. Cada uno de ustedes puede estimar la probabilidad de que muera, y debido a que las probabilidades son subjetivas, pueden diferir lo suficiente como para hacer que tal apuesta parezca favorable para ambas partes (por ejemplo, suponga que conoce una situación médica amenazante y no la revele a la aseguradora). Las compañías de seguros utilizan tablas de mortalidad como la Tabla 5.2 (que se muestra también en la Figura 5.4) para establecer sus tasas. (Curiosamente, las compañías de seguros también venden anualidades, que desde la perspectiva de un jugador son apuestas al revés, la compañía está apostando a que morirás pronto y estás apostando a que vivirás mucho tiempo).

Otra forma de pensar sobre los seguros de vida es como inversión financiera. Dado que las compañías de seguros pagan en promedio menos de lo que cobran (de lo contrario irían a la quiebra), normalmente los inversionistas harían mejor invirtiendo su dinero de otra manera, por ejemplo poniéndolo en un banco.

La mayoría de las personas que compran seguros de vida, por supuesto, no lo consideran ni como una apuesta ni una inversión, sino como una red de seguridad. Saben que si mueren, sus ingresos cesarán y quieren proporcionar un reemplazo parcial para sus dependientes, generalmente hijos y cónyuges. La prima es pequeña porque la probabilidad de muerte es baja durante los años en que dicha red de seguridad es importante, pero el beneficio en el improbable caso de muerte puede ser muy importante para los beneficiarios. Tal red de seguridad puede no ser tan importante para las personas muy ricas (que pueden permitirse la pérdida de ingresos), las personas solteras sin dependientes o las personas mayores cuyos hijos han crecido.

La Figura 5.4 y la Tabla 5.2 muestran la probabilidad de muerte durante un año, en función de la edad, para la cohorte de residentes estadounidenses nacidos en 1988 (datos de The Berkeley Mortalidad Database\(^2\)).

| Edad | Hembra | Macho | Edad | Hembra | Macho | Edad | Hembra | Macho |

|

0 |

0.008969 | 0.011126 | 40 | 0.000945 | 0.002205 | 80 | 0.035107 | 0.055995 |

| 1 | 0.000727 | 0.000809 | 41 | 0.001007 | 0.002305 | 81 | 0.038323 | 0.061479 |

| 2 | 0.000384 | 0.000526 | 42 | 0.00107 | 0.002395 | 82 | 0.041973 | 0.067728 |

| 3 | 0.000323 | 0.000415 | 43 | 0.001144 | 0.002465 | 83 | 0.046087 | 0.074872 |

| 4 | 0.000222 | 0.000304 | 44 | 0.001238 | 0.002524 | 84 | 0.050745 | 0.082817 |

| 5 | 0.000212 | 0.000274 | 45 | 0.001343 | 0.002605 | 85 | 0.056048 | 0.091428 |

| 6 | 0.000182 | 0.000253 | 46 | 0.001469 | 0.002709 | 86 | 0.062068 | 0.100533 |

| 7 | 0.000162 | 0.000233 | 47 | 0.001616 | 0.002856 | 87 | 0.06888 | 0.110117 |

| 8 | 0.000172 | 0.000213 | 48 | 0.001785 | 0.003047 | 88 | 0.076551 | 0.120177 |

| 9 | 0.000152 | 0.000162 | 49 | 0.001975 | 0.003295 | 89 | 0.085096 | 0.130677 |

| 10 | 0.000142 | 0.000132 | 50 | 0.002198 | 0.003566 | 90 | 0.094583 | 0.141746 |

| 11 | 0.000142 | 0.000132 | 51 | 0.002454 | 0.003895 | 91 | 0.105042 | 0.153466 |

| 12 | 0.000162 | 0.000203 | 52 | 0.002743 | 0.004239 | 92 | 0.116464 | 0.165847 |

| 13 | 0.000202 | 0.000355 | 53 | 0.003055 | 0.00463 | 93 | 0.128961 | 0.179017 |

| 14 | 0.000263 | 0.000559 | 54 | 0.003402 | 0.00505 | 94 | 0.142521 | 0.193042 |

| 15 | 0.000324 | 0.000793 | 55 | 0.003795 | 0.005553 | 95 | 0.156269 | 0.207063 |

| 16 | 0.000395 | 0.001007 | 56 | 0.004245 | 0.006132 | 96 | 0.169964 | 0.221088 |

| 17 | 0.000426 | 0.001161 | 57 | 0.004701 | 0.006733 | 97 | 0.183378 | 0.234885 |

| 18 | 0.000436 | 0.001254 | 58 | 0.005153 | 0.007357 | 98 | 0.196114 | 0.248308 |

| 19 | 0.000426 | 0.001276 | 59 | 0.005644 | 0.008028 | 99 | 0.208034 | 0.261145 |

| 20 | 0.000406 | 0.001288 | 60 | 0.006133 | 0.008728 | 100 | 0.220629 | 0.274626 |

| 21 | 0.000386 | 0.00131 | 61 | 0.006706 | 0.009549 | 101 | 0.234167 | 0.289075 |

| 22 | 0.000386 | 0.001312 | 62 | 0.007479 | 0.010629 | 102 | 0.248567 | 0.304011 |

| 23 | 0.000396 | 0.001293 | 63 | 0.008491 | 0.012065 | 103 | 0.263996 | 0.319538 |

| 24 | 0.000417 | 0.001274 | 64 | 0.009686 | 0.013769 | 104 | 0.280461 | 0.337802 |

| 25 | 0.000447 | 0.001245 | 65 | 0.011028 | 0.015702 | 105 | 0.298313 | 0.354839 |

| 26 | 0.000468 | 0.001226 | 66 | 0.012368 | 0.017649 | 106 | 0.317585 | 0.375342 |

| 27 | 0.000488 | 0.001237 | 67 | 0.013559 | 0.019403 | 107 | 0.337284 | 0.395161 |

| 28 | 0.000519 | 0.001301 | 68 | 0.014525 | 0.020813 | 108 | 0.359638 | 0.420732 |

| 29 | 0.00055 | 0.001406 | 69 | 0.015363 | 0.022053 | 109 | 0.383459 | 0.439252 |

| 30 | 0.000581 | 0.001532 | 70 | 0.016237 | 0.023393 | 110 | 0.408964 | 0.455882 |

| 31 | 0.000612 | 0.001649 | 71 | 0.017299 | 0.025054 | 111 | 0.437768 | 0.47619 |

| 32 | 0.000643 | 0.001735 | 72 | 0.018526 | 0.027029 | 112 | 0.466216 | 0.52 |

| 33 | 0.000674 | 0.00179 | 73 | 0.019972 | 0.029387 | 113 | 0.494505 | 0.571429 |

| 34 | 0.000705 | 0.001824 | 74 | 0.02163 | 0.032149 | 114 | 0.537037 | 0.625 |

| 35 | 0.000747 | 0.001859 | 75 | 0.023551 | 0.035267 | 115 | 0.580645 | 0.75 |

| 36 | 0.000788 | 0.001904 | 76 | 0.02564 | 0.038735 | 116 | 0.588235 | 1 |

| 37 | 0.00083 | 0.001961 | 77 | 0.027809 | 0.042502 | 117 | 0.666667 | 1 |

| 38 | 0.000861 | 0.002028 | 78 | 0.030011 | 0.046592 | 118 | 0.75 | 0 |

| 39 | 0.000903 | 0.002105 | 79 | 0.032378 | 0.051093 | 119 | 0.5 | 0 |

\(^2\)The Berkeley Mortality Database can be accessed online: http://www.demog.berkeley.edu/ bmd/states.html