8.2: Las relaciones trigonométricas

- Page ID

- 111969

Hay seis relaciones trigonométricas comunes que relacionan los lados de un triángulo rectángulo con los ángulos dentro del triángulo. Las tres relaciones estándar son el seno, el coseno y la tangente. Estos suelen abreviarse pecado, cos y bronceado. Los otros tres (cosecante, secante y cotangente) son los recíprocos del seno, coseno y tangente y a menudo se abrevian csc, sec y cot.

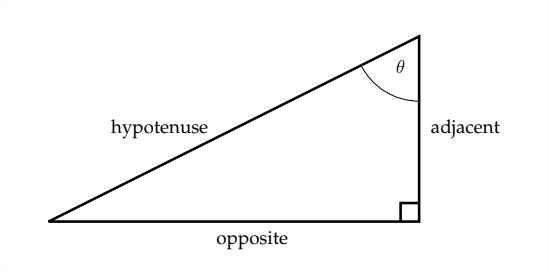

Dado un ángulo situado en un triángulo rectángulo, la función sinusoidal se define como la relación del lado opuesto al ángulo a la hipotenusa, el coseno se define como la relación del lado adyacente al ángulo a la hipotenusa y la tangente se define como la relación del lado opuesto al ángulo al lado adyacente al ángulo.

\ [

\ begin {aligned}

\ sin\ theta &=\ frac {o p p} {h y p}\\

\ cos\ theta &=\ frac {a d j} {h y p}\\

\ tan\ theta &=\ frac {o p p} {a d j}

\ end {alineado}

\]

Un dispositivo monumónico común para ayudar a recordar estos relaciones es

-Sohcahtoa-que identifica el pecado como Opp sobre Hyp Cos como Adj sobre Hyp y el Tan como Opp sobre Adj.

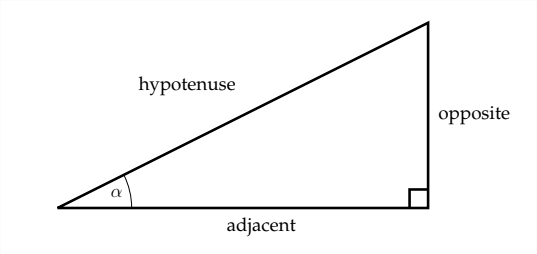

Un ángulo agudo colocado en la otra posición de un triángulo rectángulo tendría diferentes lados oppositos y adyacentes aunque la hipotenusa permanecería igual.

Ejemplos: Ratios trigonométricos

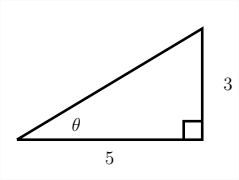

Encontrar\(\sin \theta, \cos \theta\) y\(\tan \theta\) para el ángulo\(\theta\)

dado Para encontrar el pecado y cos del ángulo\(\theta\), primero debemos encontrar la hipotenusa usando el Teorema de Pitágoras \(\left(a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}\right)\)

ya que conocemos las patas del triángulo, podemos sustituir estos valores por\(a\) y\(b\) en el Teorema de Pitágoras:

\ [

\ begin {array} {c}

3^ {2} +5^ {2} =c^ {2}\\

9+25=c^ {2}\\

34=c^ {2}\

\ sqrt {34} =c

\ end {array }

\]

Ahora que conocemos la hipotenusa\((\sqrt{34}),\) podemos determinar el pecado, cos y bronceado para el ángulo\(\theta\)

\ [

\ begin {alineado}

\ sin\ theta &=\ frac {3} {\ sqrt {34}}\\

\ cos\ theta &=\ frac {5} {\ sqrt {34}}\\

\ tan\ theta &=\ frac {3} {5}

\ end {alineado}

\]

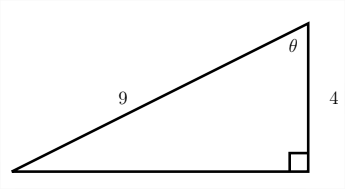

Buscar\(\sin \theta, \cos \theta\) y\(\tan \theta\) para el ángulo dado\(\theta\)

Nuevamente, para encontrar el pecado, cos y tan del ángulo\(\theta,\) debemos encontrar el lado faltante del triángulo usando el Teoreoreas de Pitágoras. ya que, en este caso, conocemos la hipotenusa y una de las piernas, se debe sustituir el valor de la hipotenusa\(c\) y la longitud de la pierna estamos dado puede ser sustituido por cualquiera

\(a\) o\(b\)

\ [

\ begin {array} {c}

4^ {2} +b^ {2} =9^ {2}\\

16+b^ {2} =81\\

b^ {2} =65\\

b=\ sqrt {65}

\ end {array}

\]

Ahora que conocemos la longitud de la otra pata del triángulo\((\sqrt{65}),\) podemos determinar el pecado, cos y para el bronceado angle\(\theta\)

\ [

\ begin {aligned}

\ sin\ theta &=\ frac {\ sqrt {65}} {9}\

\\ cos\ theta &=\ frac {4} {9}\

\\ tan\ theta &=\ frac {\ sqrt {65}} {4}

\ end {alineado}

\]

Además de los ejemplos anteriores, si estamos dado el valor de una de las relaciones trigonométricas, podemos encontrar el valor de las otras dos.

Ejemplo

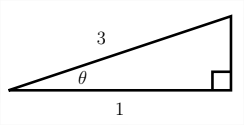

Dado que\(\cos \theta=\frac{1}{3},\) encontrar\(\sin \theta\) y\(\tan \theta\)

Dada la información sobre el coseno del ángulo\(\theta,\) podemos crear un triángulo que nos permitirá encontrar\(\sin \theta\) y\(\tan \theta\)

Usando el Teorema de Pitágoras, podemos encontrar el lado faltante del triángulo:

\ [

\ begin {array} {c}

a^ {2} +1^ {2} =3^ {2}\\

a^ {2} +1=9

\ end {array}

\]

\(a^{2}=8\)

\(a=\sqrt{8}=2 \sqrt{2}\)

Entonces\(\sin \theta=\frac{\sqrt{8}}{3}\) y\(\tan \theta=\frac{\sqrt{8}}{1}=\sqrt{8}\)

Podrías decirte a ti mismo: “Espera un minuto, solo porque el coseno del ángulo\(\theta\) es\(\frac{1}{3},\) eso no significa necesariamente que los lados del triángulo sean 1 y\(3,\) podrían ser 2 y\(6,\) o 3 y 9 o cualquier valor\(n\) y\(3 n . "\)

Esto es cierto, y si los lados se expresan como\(n\) y\(3 n,\) entonces el lado faltante sería\(n \sqrt{8},\) para que cada vez que encontremos una relación trigonométrica, el\(n^{\prime}\) s se cancelará, así que simplemente los dejamos afuera para empezar y llamar a los lados 1 y 3

Ejemplo

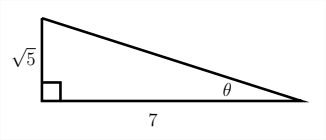

Dado ese\(\tan \theta=\frac{\sqrt{5}}{7},\) hallazgo\(\sin \theta\) y\(\cos \theta\)

Primero tomaremos la información sobre la tangente y usaremos esta para dibujar un triángulo.

Luego usa el Teorema de Pitágoras para encontrar el lado faltante del triángulo:

\ [\ begin {array} {c}

\ sqrt {5} ^ {2} +7^ {2} =c^ {2}\\

5+49=c^ {2}\\

54=c^ {2}

\\ sqrt {54} =3\ sqrt {6} =c

\ end {array}

\]

Entonces:

\ [

\ sin\ theta=\ frac {\ sqrt {5}} {\ sqrt {54}} =\ sqrt {\ frac {5} {54}}

\]

\ [

\ cos\ theta=\ frac {7} {\ sqrt {54}} =\ frac {7} {3\ sqrt {6}}

\]

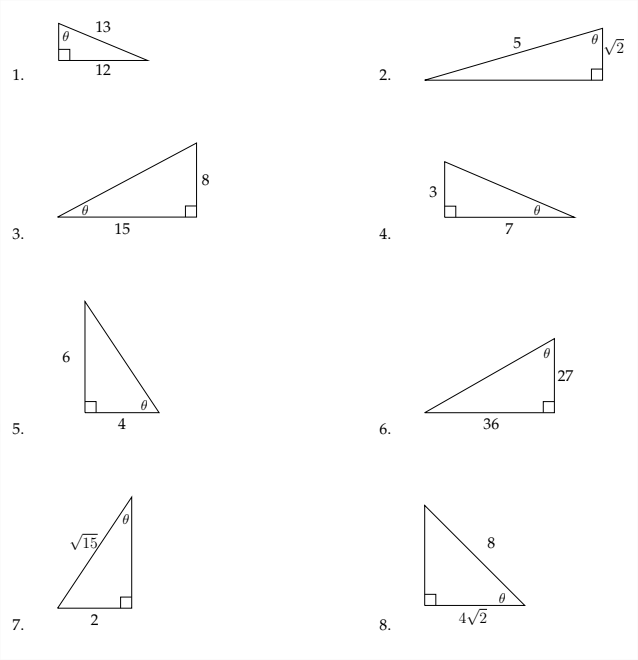

Ejercicios 1.2

Encontrar\(\sin \theta, \cos \theta\) y\(\tan \theta\) para los triángulos dados.

Utilice la información proporcionada para encontrar las otras dos relaciones trigonométricas.

11. \(\quad \tan \theta=\frac{1}{2}\)

12. \(\quad \sin \theta=\frac{3}{4}\)

13. \(\quad \cos \theta=\frac{3}{\sqrt{20}}\)

14. \(\quad \tan \theta=2\)

15. \(\sin \theta=\frac{5}{\sqrt{40}}\)

16. \(\sin \theta=\frac{7}{10}\)

17. \(\cos \theta=\frac{9}{40}\)

18. \(\quad \tan \theta=\sqrt{3}\)

19. \(\cos \theta=\frac{1}{2}\)

20. \(\cos \theta=\frac{3}{7}\)

21. \(\sin \theta=\frac{\sqrt{5}}{7}\)

22. \(\quad \tan \theta=1.5\)