6.1: Preludio al Conteo Pólya—Redfield

- Page ID

- 117072

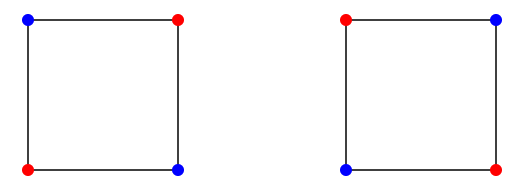

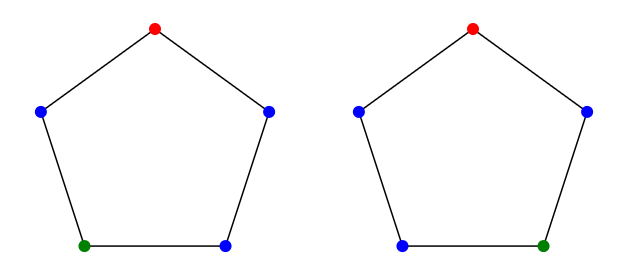

Hemos hablado de la cantidad de formas de colorear correctamente una gráfica con\(k\) colores, dada por el polinomio cromático. Por ejemplo, el polinomio cromático para la gráfica en la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) es\(k^4 - 4k^3 + 6k^2 - 3k\), y\(f(2)=2\). Los dos colorantes se muestran en la figura, pero en un sentido obvio son de la misma coloración, ya que uno se puede convertir en el otro simplemente girando la gráfica. Consideraremos un tipo de problema de coloración ligeramente diferente, en el que contamos los colores “verdaderamente diferentes” de los objetos.

Muchos de los “objetos” que coloreamos parecerán gráficos, pero generalmente nos interesarán como objetos geométricos en lugar de gráficos, y no requeriremos que los vértices adyacentes sean de colores diferentes. Esto simplificará los problemas; también se puede hacer contar el número de diferentes coloraciones adecuadas de las gráficas, pero es más complicado.

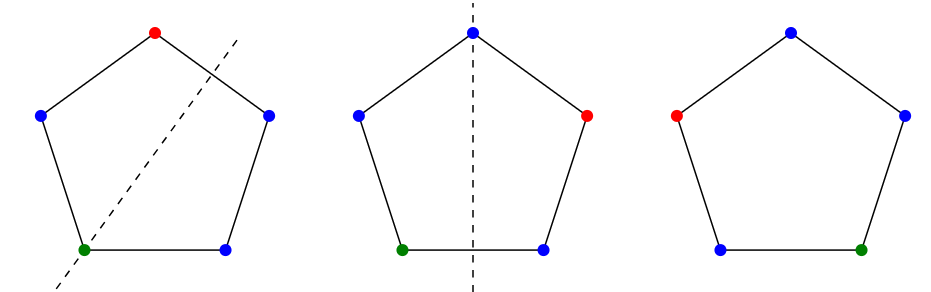

So consider this problem: How many different ways are there to color the vertices of a regular pentagon with \(k\) colors? The number of ways to color the vertices of a fixed pentagon is \(k^5\), but this includes many duplicates, that is, colorings that are really the same. But what do we mean by "the same'' in this case? We might mean that two colorings are the same if we can rotate one to get the other. But what about the colorings in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)? Are they the same? Neither can be rotated to produce the other, but either can be flipped or reflected through a vertical line to produce the other. In fact we are free to decide what "the same'' means, but we will need to make sure that our requirements are consistent.

As an example of what can go wrong if we're not careful, note that there are five lines through which the pentagon can be reflected onto itself. Suppose we want to consider colorings to be "the same'' if one can be produced from the other by a reflection, but not if one can be obtained from the other by rotation. Surely if one coloring can be obtained by two reflections in a row from another, then these colorings should also be the same. But two reflections in a row equal a rotation, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). So whenever we have some motions that identify two colorings, we are required to include all combinations of the motions as well. In addition, any time we include a motion, we must include the "inverse'' motion. For example, if we say a rotation by \(54^\circ\) degrees produces a coloring that we consider to be the same, a rotation by \(-54^\circ\) must be included as well (we may think of this as a rotation by \(306^\circ\)). Finally, since any coloring is the same as itself, we must always include the "trivial'' motion, namely, doing nothing, or rotation by \(0^\circ\) if you prefer.