8.7: Elaboración de radioisótopos para usos médicos

- Page ID

- 77321

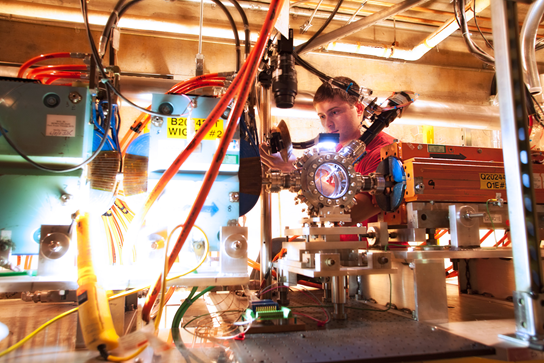

Los radioisótopos naturales suelen tener una vida media larga y no son los más adecuados para aplicaciones médicas. La aplicación médica suele requerir radioisótopos de corta duración. Los radioisótopos se producen generalmente en reactores nucleares donde\(\ce{\alpha}\) abundan las partículas, como\(\ce{\beta}\) partículas, partículas y neutrones. Los aceleradores de partículas, como el que se muestra en la Fig. 8.7.1, también aceleran y dirigen las partículas nucleares hacia las dianas. Las partículas nucleares de alta energía pueden ser absorbidas por y transmutar los núcleos diana a radioisótopos en una reacción nuclear.

Los radioisótopos en aplicaciones médicas generalmente se producen mediante el método de bombardeo de partículas. Una reacción que ocurre naturalmente por el bombardeo de neutrones de los rayos cósmicos sobre el nitrógeno-14 es la siguiente.

\[\ce{_7^14N + _{0}^{1}{n} -> _6^14C + _{1}^{1}{p}}\nonumber\]

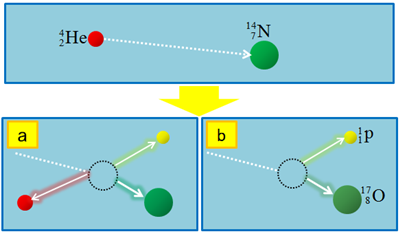

Un ejemplo de una reacción nuclear artificial iniciada por bombardeo de\(\ce{\alpha}\) partículas sobre nitrógeno, observada por Rutherford que condujo al descubrimiento de protones, se ilustra en la Fig. 8.7.2.

\[\ce{_2^4He + _{7}^{14}{N} -> _8^17O + _{1}^{1}{p}}\nonumber\]

Otro ejemplo es la reacción nuclear iniciada por\(\ce{\alpha}\) -partículas sobre berilio, observada por James Chadwick, que llevaron al descubrimiento del neutrón.

\[\ce{_2^4He + _{4}^{9}{Be} -> _6^12C + _{0}^{1}{n}}\nonumber\]

Un ejemplo de producción de radioisótopos para usos médicos es el siguiente. El oro-198, utilizado como trazador en el hígado, es producido por bombardeo de neutrones sobre oro-197.

\[\ce{_79^197Au + _{0}^{1}{n} -> _79^198Au}\nonumber\]

De igual manera, el galio-67 utilizado en diagnósticos médicos es producido por bombardeo de protones sobre zinc-66.

\[\ce{_30^66Zn + _{1}^{1}{p} -> _31^67Ga}\nonumber\]

El molibdeno-99 es un isótopo radiactivo producido en un reactor nuclear por bombardeo de neutrones de molibdeno-98.

\[\ce{_42^98Mo + _{0}^{1}{n} -> _42^99Mo} + \gamma\nonumber\]

El molibdeno-99 también se produce como producto de fisión del uranio-235. El molibdeno-99 se desintegró a tecnecio-99m que tiene varios usos en imágenes y tratamiento médico nuclear.

\[\ce{_42^99Mo -> _43^{99m}{Tc} + _{-1}^{0}{e}}\nonumber\]

El tecnecio-99m es de corta duración (semivida 6 h) y necesita ser producido en el hospital para minimizar su descomposición durante el transporte. Su origen molibdeno-99 tiene una vida media de 66h y puede transportarse sin decaimiento significativo durante el transporte. Los generadores de molibdeno-99/tecnecio-99m se suministran a los hospitales en un contenedor blindado. La Fig. 8.7.3 ilustra el primer generador de molibdeno-99/tecnecio-99m desarrollado en el Laboratorio Nacional Brookhaven. El ion molibdato (MoO 4 2) se adsorbe sobre adsorbente de alúmina en una columna. Cuando molibdeno-99 decae a tecnecio-99m, el ion cambia a pertecnetato (TCo 4 ‑), que está menos unido a la alúmina. Al verter una solución salina a través de la columna se eluye el tecnecio-99m como ion TCo 4 ‑, que luego se utiliza con fines médicos en los hospitales.

También se ha probado la destrucción de un tumor inoperable por\(\ce{\alpha}\) emisión de boro-10 tras bombardeo de neutrones.

\[\ce{_{0}^{1}{n} + _5^10B -> _4^7Li + _2^4He}\nonumber\]