7.4: Resolución de problemas

- Page ID

- 143177

Objetivos de aprendizaje

- Describir estrategias de resolución de problemas

- Definir algoritmo y heurística

- Explicar algunos bloqueos comunes para la resolución efectiva de problemas

Las personas enfrentan problemas todos los días, generalmente, múltiples problemas a lo largo del día. En ocasiones estos problemas son sencillos: Para duplicar una receta de masa de pizza, por ejemplo, todo lo que se requiere es que se duplique cada ingrediente de la receta. A veces, sin embargo, los problemas que encontramos son más complejos. Por ejemplo, digamos que tienes un plazo de trabajo, y debes enviar por correo una copia impresa de un reporte a tu supervisor antes del final del día hábil. El reporte es sensible al tiempo y debe ser enviado de la noche a la mañana. Anoche terminaste el reporte, pero tu impresora no funcionará hoy. ¿Qué debes hacer? Primero, es necesario identificar el problema y luego aplicar una estrategia para resolverlo.

Estrategias de resolución de problemas

Cuando se le presenta un problema, ya sea un problema matemático complejo o una impresora rota, ¿cómo lo resuelve? Antes de encontrar una solución al problema, primero se debe identificar claramente el problema. Después de eso, se puede aplicar una de las muchas estrategias de resolución de problemas, ojalá resulte en una solución.

Una estrategia de resolución de problemas es un plan de acción utilizado para encontrar una solución. Diferentes estrategias tienen diferentes planes de acción asociados a ellas (Ver Tabla\(\PageIndex{1}\) a continuación). Por ejemplo, una estrategia bien conocida es el ensayo y error. El viejo adagio, “Si al principio no tienes éxito, inténtalo, inténtalo de nuevo” describe el ensayo y error. En términos de su impresora rota, podría intentar verificar los niveles de tinta, y si eso no funciona, podría verificar para asegurarse de que la bandeja de papel no esté atascada. O tal vez la impresora no esté realmente conectada a su computadora portátil. Al usar prueba y error, seguirías probando diferentes soluciones hasta que resolvieras tu problema. Aunque el ensayo y error no suele ser una de las estrategias más eficientes en el tiempo, es una estrategia de uso común.

| Método | Descripción | Ejemplo |

|---|---|---|

| Prueba y error | Continuar probando diferentes soluciones hasta que se solucione el problema | Reiniciar el teléfono, apagar WiFi, apagar el bluetooth para determinar por qué tu teléfono está funcionando mal |

| Algorithm | Fórmula paso a paso para resolver problemas | Manual de instrucciones para instalar software nuevo en su computadora |

| Heurística | Marco general de resolución de problemas | Trabajando hacia atrás; dividiendo una tarea en pasos |

Otro tipo de estrategia es un algoritmo. Un algoritmo es una fórmula de resolución de problemas que le proporciona instrucciones paso a paso utilizadas para lograr el resultado deseado (Kahneman, 2011). Se puede pensar en un algoritmo como una receta con instrucciones muy detalladas que producen el mismo resultado cada vez que se realizan. Los algoritmos se utilizan con frecuencia en nuestra vida cotidiana, especialmente en la informática. Cuando ejecutas una búsqueda en Internet, los motores de búsqueda como Google utilizan algoritmos para decidir qué entradas aparecerán primero en tu lista de resultados. Facebook también utiliza algoritmos para decidir qué publicaciones mostrar en tu fuente de noticias. ¿Se pueden identificar otras situaciones en las que se utilizan algoritmos?

Una heurística es otro tipo de estrategia de resolución de problemas. Si bien se debe seguir un algoritmo exactamente para producir un resultado correcto, una heurística es un marco general de resolución de problemas (Tversky y Kahneman, 1974). Se puede pensar en estos como atajos mentales que se utilizan para resolver problemas. Una “regla general” es un ejemplo de una heurística. Tal regla le ahorra tiempo y energía a la persona a la hora de tomar una decisión, pero a pesar de sus características de ahorro de tiempo, no siempre es el mejor método para tomar una decisión racional. Se utilizan diferentes tipos de heurística en diferentes tipos de situaciones, pero el impulso de usar una heurística ocurre cuando se cumple una de las cinco condiciones (Pratkanis, 1989):

- Cuando uno se enfrenta a demasiada información

- Cuando el tiempo para tomar una decisión es limitado

- Cuando la decisión a tomar no es importante

- Cuando hay acceso a muy poca información para usar en la toma de la decisión

- Cuando una heurística apropiada pasa a venir a la mente en un mismo momento

Trabajar al revés es una heurística útil en la que comienzas a resolver el problema enfocándote en el resultado final. Considera este ejemplo: Vives en Washington, D.C. y has sido invitado a una boda\(\text{4 PM}\) el sábado en Filadelfia. Sabiendo que Interstate\(95\) tiende a retroceder cualquier día de la semana, debes planificar tu ruta y cronometrar tu salida en consecuencia. Si quieres estar en el servicio de bodas\(\text{3:30 PM}\), y lleva\(2.5\) horas llegar a Filadelfia sin tránsito, ¿a qué hora deberías salir de tu casa? Usas la heurística de trabajo al revés para planificar los eventos de tu día de forma regular, probablemente sin siquiera pensarlo.

Otra heurística útil es la práctica de lograr una meta o tarea grande dividiéndola en una serie de pasos más pequeños. Los estudiantes suelen utilizar este método común para completar un gran proyecto de investigación o ensayo largo para la escuela. Por ejemplo, los estudiantes suelen hacer una lluvia de ideas, desarrollar una tesis o tema principal, investigar el tema elegido, organizar su información en un esquema, escribir un borrador aproximado, revisar y editar el borrador aproximado, desarrollar un borrador final, organizar la lista de referencias y revisar su trabajo antes de entregar el proyecto. La gran tarea se vuelve menos abrumadora cuando se descompone en una serie de pequeños pasos.

EVERYDAY CONNECTION: Solving Puzzles

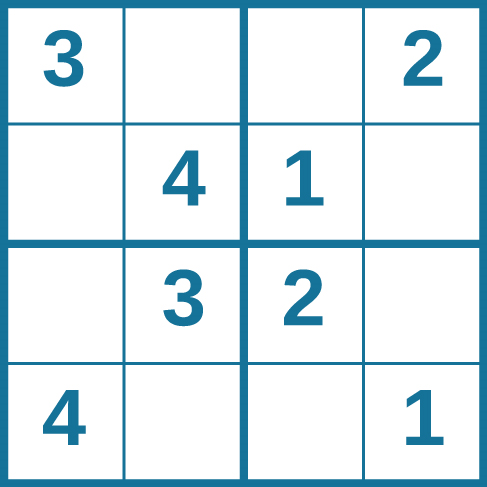

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. Sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a \(9\times 9\) grid. The simple sudoku below is a \(4\times 4\) grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: \(1\), \(2\), \(3\), or \(4\). Here are the rules: The numbers must total \(10\) in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Time yourself as you solve this puzzle and compare your time with a classmate.

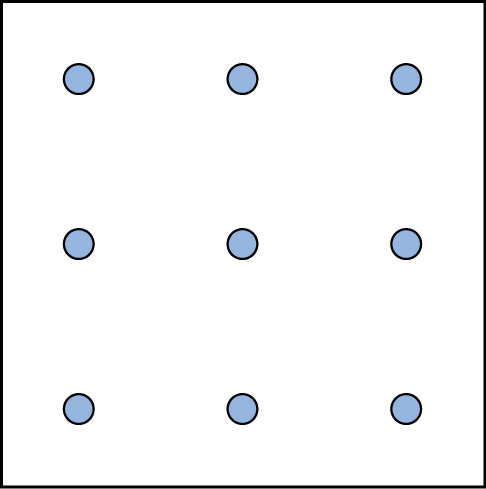

Here is another popular type of puzzle that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper:

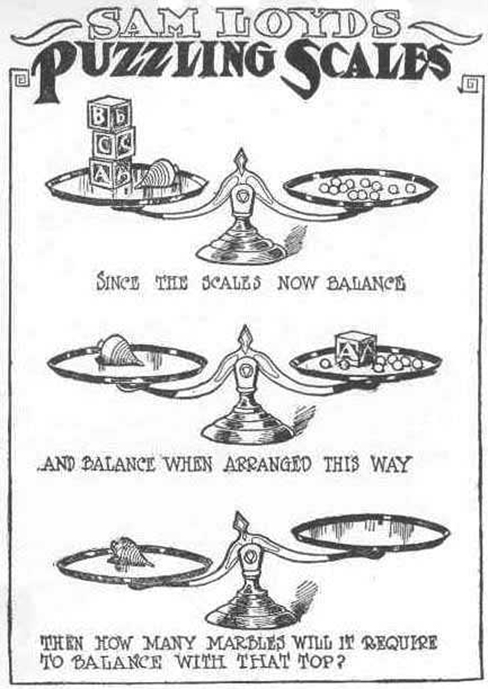

Take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below. Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime (Cyclopedia of Puzzles, n.d.).

Pitfalls to Problem Solving

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. For example, let’s say you and three friends wanted to rent a house and had a combined target budget of \(\$1,600\). The realtor shows you only very run-down houses for \(\$1,600\) and then shows you a very nice house for \(\$2,000\). Might you ask each person to pay more in rent to get the \(\$2,000\) home? Why would the realtor show you the run-down houses and the nice house? The realtor may be challenging your anchoring bias. An anchoring bias occurs when you focus on one piece of information when making a decision or solving a problem. In this case, you’re so focused on the amount of money you are willing to spend that you may not recognize what kinds of houses are available at that price point.

The confirmation bias is the tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs. For example, if you think that your professor is not very nice, you notice all of the instances of rude behavior exhibited by the professor while ignoring the countless pleasant interactions he is involved in on a daily basis. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that the event you just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t. In other words, you knew all along that things would turn out the way they did. Representative bias describes a faulty way of thinking, in which you unintentionally stereotype someone or something; for example, you may assume that your professors spend their free time reading books and engaging in intellectual conversation, because the idea of them spending their time playing volleyball or visiting an amusement park does not fit in with your stereotypes of professors.

Finally, the availability heuristic is a heuristic in which you make a decision based on an example, information, or recent experience that is that readily available to you, even though it may not be the best example to inform your decision. Biases tend to “preserve that which is already established—to maintain our preexisting knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and hypotheses” (Aronson, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). These biases are summarized in the Table \(\PageIndex{2}\) below.

| Bias | Description |

|---|---|

| Anchoring | Tendency to focus on one particular piece of information when making decisions or problem-solving |

| Confirmation | Focuses on information that confirms existing beliefs |

| Hindsight | Belief that the event just experienced was predictable |

| Representative | Unintentional stereotyping of someone or something |

| Availability | Decision is based upon either an available precedent or an example that may be faulty |

Were you able to determine how many marbles are needed to balance the scales in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)? You need nine.

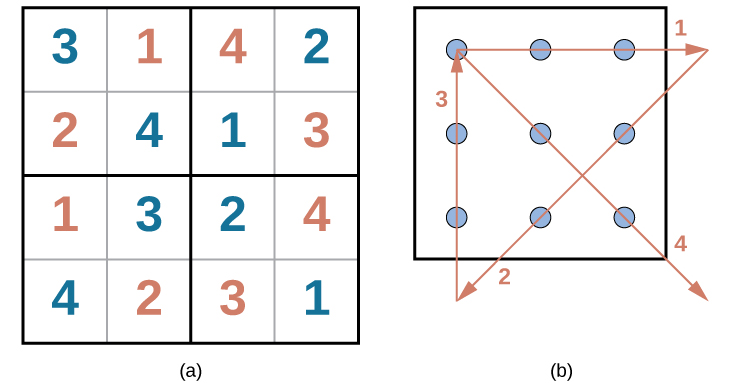

Were you able to solve the problems in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) and Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)? Here are the answers:

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Solutions to the puzzles in Everyday Connection

Summary

Many different strategies exist for solving problems. Typical strategies include trial and error, applying algorithms, and using heuristics. To solve a large, complicated problem, it often helps to break the problem into smaller steps that can be accomplished individually, leading to an overall solution. Roadblocks to problem solving include a mental set, functional fixedness, and various biases that can cloud decision making skills.

Glossary

- algorithm

- problem-solving strategy characterized by a specific set of instructions

- anchoring bias

- faulty heuristic in which you fixate on a single aspect of a problem to find a solution

- availability heuristic

- faulty heuristic in which you make a decision based on information readily available to you

- confirmation bias

- faulty heuristic in which you focus on information that confirms your beliefs

- functional fixedness

- inability to see an object as useful for any other use other than the one for which it was intended

- heuristic

- mental shortcut that saves time when solving a problem

- hindsight bias

- belief that the event just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t

- mental set

- continually using an old solution to a problem without results

- problem-solving strategy

- method for solving problems

- representative bias

- faulty heuristic in which you stereotype someone or something without a valid basis for your judgment

- trial and error

- problem-solving strategy in which multiple solutions are attempted until the correct one is found

- working backwards

- heuristic in which you begin to solve a problem by focusing on the end result