23.14: Universo

- Page ID

- 109487

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)¿Qué hay al borde del Universo?

Esta imagen es de los objetos más lejanos del Universo. Fue tomada por el Telescopio Espacial Hubble. La imagen mira hacia atrás alrededor de 13 mil millones de años. Las galaxias en esta imagen eran todas muy jóvenes. Han tardado 13 mil millones de años para que su luz llegue a nosotros.

El Universo

El estudio del Universo se llama cosmología. Los cosmólogos estudian la estructura y los cambios en el Universo actual. El Universo contiene todos los sistemas estelares, galaxias, gas y polvo. También estudian toda la materia y la energía que existe ahora, existió en el pasado, existirá en el futuro. El Universo incluye todo el espacio y el tiempo.

Comprensión Humana del Universo

¿Qué reconocían los antiguos griegos como el Universo? Su Universo tenía la Tierra en el centro, el Sol, la Luna, cinco planetas, y una esfera a la que estaban unidas todas las estrellas. Esta idea se mantuvo durante muchos siglos. Galileo y su telescopio ayudaron a la gente a reconocer que la Tierra no es el centro del Universo. También descubrieron que hay muchas más estrellas de las que eran visibles a simple vista. Todas esas estrellas estaban en la Vía Láctea.

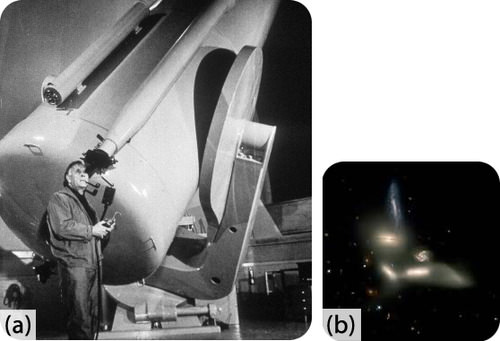

A principios del siglo XX, un astrónomo llamado Edwin Hubble (Figura abajo) descubrió algo increíble. Mostró que la Nebulosa de Andrómeda estaba a más de 2 millones de años luz de distancia. Esto fue muchas veces más lejos que las distancias más lejanas que jamás se habían medido. Hubble se dio cuenta de que muchos de los objetos que los astrónomos llamaban nebulosas no eran en realidad nubes de gas. Eran colecciones de millones o miles de millones de estrellas. Ahora llamamos a estas características galaxias.

(a) Edwin Hubble utilizó el telescopio reflectante de 100 pulgadas en el Observatorio Mount Wilson en California para mostrar que algunas motas distantes de luz eran galaxias. (b) El telescopio espacial homónimo del Hubble detectó este grupo de seis galaxias. Edwin Hubble demostró la existencia de galaxias.

Hubble demostró que el Universo era mucho más grande que nuestra propia galaxia. Hoy, sabemos que el Universo contiene alrededor de cien mil millones de galaxias. Esto es aproximadamente el mismo número de galaxias que hay estrellas en la Vía Láctea.

Resumen

- El Universo contiene alrededor de cien mil millones de galaxias.

- La idea de un Universo ha cambiado a través de la historia humana.

- Edwin Hubble determinó que había mucho más en el espacio que nuestra propia galaxia.

Revisar

- ¿Qué estudian los cosmólogos?

- ¿Cuál era la importancia de que Edwin Hubble viera que la nebulosa de Andrómeda era en realidad una galaxia?

- ¿Qué es lo que conforma el Universo?

Referencias

| Imagen | Referencia | Atribuciones |

|---|---|---|

|

[Figura 1] |

Crédito: a) Cortesía de la NASA; (b) Cortesía de NASA, J. English (U. Manitoba), S. Hunsberger, S. Zonak, J. Charlton, S. Gallagher (PSU), y L. Frattare (STSCi) Fuente: (a) quest.arc.nasa.gov/hst/about/edwin.html; (b) http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/arc...02/22/image/a/ Licencia: Dominio público |

|

[Figura 2] |

Crédito: a) Cortesía de la NASA; (b) Cortesía de NASA, J. English (U. Manitoba), S. Hunsberger, S. Zonak, J. Charlton, S. Gallagher (PSU), y L. Frattare (STSCi) Fuente: (a) quest.arc.nasa.gov/hst/about/edwin.html; (b) http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/arc...02/22/image/a/ Licencia: Dominio público |