1.4: Curvas Planas

- Page ID

- 131057

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Curvas Planas Expresadas en\( x-y\) Coordenadas

La Figura I.7 muestra cómo una longitud elemental\( \delta s \) is related to the corresponding increments in \( x \) and \( y \):

\[ \delta s = \sqrt{\delta x^{2} + \delta y^{2}} = \sqrt{1+\left(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\right)^{2}} \delta x = \sqrt{ \left(\dfrac{dx}{dy}\right)^{2} + 1} \, dy \label{eq:1.4.1} \]

Considere un alambre de masa por unidad de longitud (densidad lineal)\( \lambda \) bent into the shape \( y = y(x) \) between \( x = a \) and \( x=b \). The mass of an element \( ds \) is \( \lambda \delta s \) , por lo que la masa total es

\[ \int \lambda \,ds = \int_a^b \lambda \sqrt{1 + \left(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\right)^{2}} \, dx \label{eq:1.4.2} \]

Los primeros momentos de misa sobre la\( y \) - and \( x \) -axes are respectively

\[ \int_a^b \lambda x \sqrt{ 1+ \left(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\right)^2} \, dx \label{eq:1.4.3A} \]

y

\[ \int_a^b \lambda y \sqrt{ 1+ \left(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\right)^2} \, dx \label{eq:1.4.3B} \]

Si el cable es uniforme y\( \lambda \) is therefore not a function of \( x \) or \( y \), \( \lambda \) can come outside the integral signs in Equations \( \ref{eq:1.4.2}\) - \( \ref{eq:1.4.3B}\), and we hence obtain

\[ \overline{x} = \dfrac{\displaystyle \int_a^b x \sqrt{ 1+\left( \dfrac{dy}{dx} \right)^2} dx } { \displaystyle \int_a^b \sqrt{ 1+ \left(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\right)^2} dx} \label{eq:1.4.4A} \]

y

\[ \overline{y} = \dfrac{\displaystyle \int_a^b y \sqrt{ 1+\left( \dfrac{dy}{dx} \right)^2} dx } { \displaystyle \int_a^b \sqrt{ 1+ \left(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\right)^2} dx} \label{eq:1.4.4B} \]

siendo el denominador en cada una de estas expresiones simplemente la longitud total del cable.

Considera un alambre uniforme doblado en la forma del semicírculo\( x^{2} + y^{2} = a^{2} \), \( x >0 \).

En primer lugar, cabe señalar que uno esperaría\( \overline{x} > 0.4244a \) (el valor para una lámina semicircular plana).

La longitud (es decir, los denominadores en Ecuaciones\( \ref{eq:1.4.4A}\) and \( \ref{eq:1.4.4B}\)) is just \( \pi a \). Since there are, between \( x \) and \( x + \delta x \), two elemental lengths to account for, one above and one below the \( x \) axis, the numerator of Equation \( \ref{eq:1.4.4A}\) must be

\[2 \int_0^a x \sqrt{1+ \left(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\right)^{2}} dx \nonumber \]

En este caso

\[y = \sqrt{a^2 - x^2} \nonumber \]

y

\[ \dfrac{dy}{dx} = \dfrac{-x}{ \sqrt{a^2 - x^2} } \nonumber \]

El primer momento de longitud de todo el semicírculo es

\[\overline{x} = 2 \int_0^a x \sqrt{ 1 + \dfrac{x^2}{a^2-x^2} } dx = 2a \int_0^a \dfrac{x\,dx}{ \sqrt{ a^2-x^2 }} \nonumber \]

A partir de este punto el alumno se deja a sus propios dispositivos para resolver esta integral y derivar\( \overline{x} = \dfrac{2a}{\pi} = 0.6366a \).

Curvas Planas Expresadas en Coordenadas Polares

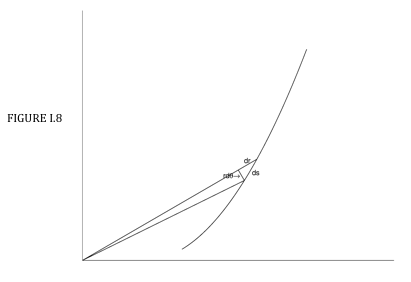

La Figura I.8 muestra cómo una longitud elemental\( \delta s \) is related to the corresponding increments in \( r \) and \( \theta \) :

\[ \delta s = \sqrt{( \delta r)^{2} + (r \delta \theta )^{2}} = \sqrt{\left( \dfrac{dr}{d \theta }\right)^{2} + r^{2}} \, \delta \theta = \sqrt{1+\left(r \dfrac{d \theta }{dr}\right)^{2}} \,\delta r. \label{eq:1.4.5} \]

La masa de la curva (entre\( \theta = a \) y\( \theta = b \) ) es

\[ \int_ \alpha ^ \beta \lambda \sqrt{ \left(\dfrac{dr}{d \theta }\right) ^{2} + r^{2}} \, d \theta. \nonumber \]

Los primeros momentos sobre el\( y \) - and \( x \) -axes are (recalling that \( x = r \cos \theta \) and \( y = r \sin \theta \) )

\[ \int_ \alpha ^ \beta \lambda r \cos \theta \sqrt{ \left(\dfrac{dr}{d \theta }\right) ^{2} + r^{2}} \, d \theta \nonumber \]

y

\[ \int_ \alpha ^ \beta \lambda r \sin \theta \sqrt{ \left(\dfrac{dr}{d \theta }\right) ^{2} + r^{2}} \, d \theta. \nonumber \]

Si no\( \lambda \) es una función de\( r \) or \( \theta \) , obtenemos

\[ \overline{x} = \dfrac{1}{L} \int_ \alpha ^ \beta r \cos \theta \sqrt{ \left(\dfrac{dr}{d \theta }\right) ^{2} + r^{2}} \, d \theta \label{eq:1.4.6A} \]

y

\[ \overline{y} = \dfrac{1}{L} \int_ \alpha ^ \beta r \sin \theta \sqrt{ \left(\dfrac{dr}{d \theta }\right) ^{2} + r^{2}} d \theta \label{eq:1.4.6B} \]

donde e\(L\) es la longitud del cable.

Consideremos nuevamente el alambre uniforme de la Figura I.8 doblado en forma de semicírculo. La ecuación en coordenadas polares es simple\( r = a \), and the integration limits are \( \theta = \dfrac{- \pi}{2} \) to \( \theta = \dfrac{+ \pi}{2} \) y la longitud es\( \pi a \) .

Así

\[ \overline{x} = \dfrac{1}{ \pi a} \int_{- \pi/2} ^{+ \pi/2} acos \theta [ 0 - a^{2}]^ \frac{1}{2} d \theta = \dfrac{2a}{ \pi } . \nonumber \]

El lector debería ahora encontrar la posición del centro de masa de un alambre doblado en el arco de un círculo de ángulo a\( 2 \alpha \). The expression obtained should go to \( \dfrac{2 a }{\pi} \) medida que\( \alpha \) va a\( \dfrac{\pi}{2} \), and to \( a \) as \( \alpha \) va a cero.