3.7: Uso de la búsqueda inversa de imágenes de Google

- Page ID

- 100977

Using Google Reverse Image Search

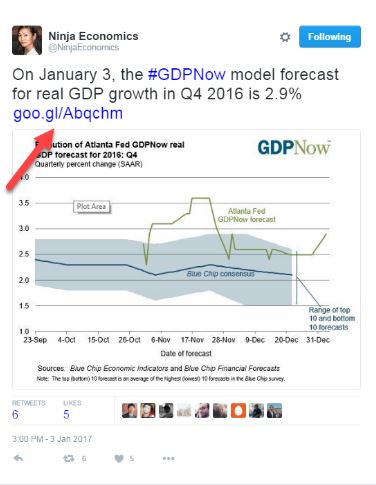

Most of the time finding the origin of an image on Twitter is easy. Just follow the links. For instance, take the chart in this tweet from Twitter user @NinjaEconomics. Should you evaluate it it by figuring out who @NinjaEconomics is?

Nope. Just follow that link to the source. It’s usually the last part of a tweet.

If you do follow that link, the chart is there, with a bunch more information about the data behind it and how it was produced. It’s from the Atlanta Federal Reserve, and it’s the Fed — not @NinjaEconomics — that you want to evaluate.

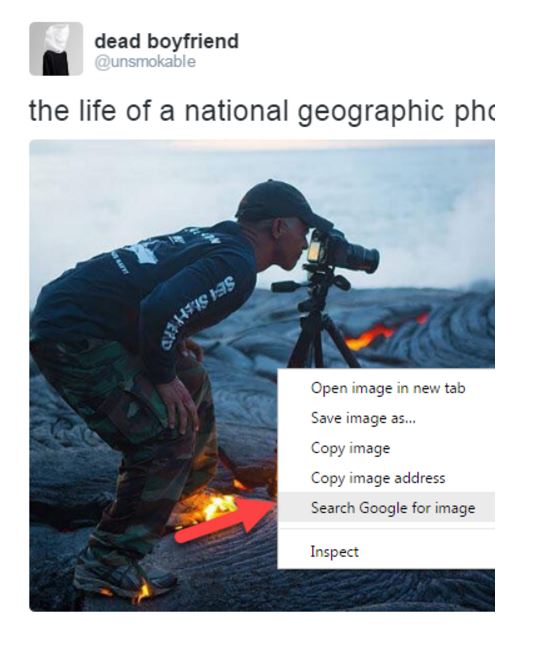

But sometimes people will post a photo that has no source, as this person does here:

So we have questions.

First, is this actually a National Geographic photographer?

More importantly, is this real? Is that lava so hot that it will literally set a metal tripod on fire? That seems weird, but we’re not lava experts.

There’s no link here, so we’re going to use reverse image search. If you’re using Google Chrome as a browser (which you should be for this class) put the cursor over the photo and right-click (control-click on a Mac). A “context menu” will pop up and one of the options will be “Search Google for image.”

(For the sake of narrative simplicity we will show solutions in this text as they would be implemented in Chrome. Classes using this text are advised to use Chrome where possible. The appendix contains notes about translating these tactics to other browsers, and you can of course search the web for the Firefox and Safari corollaries.)

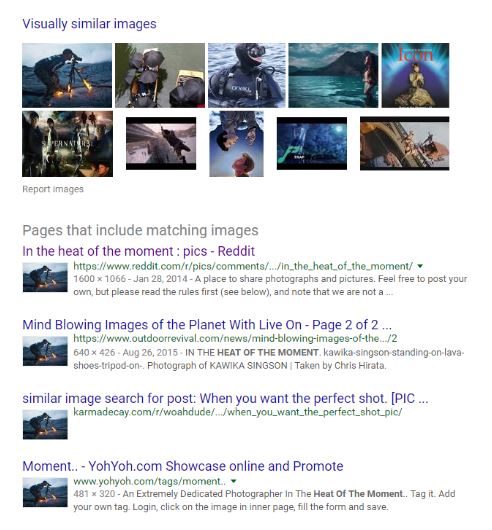

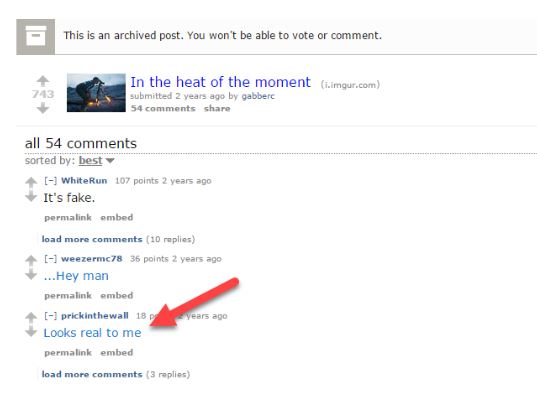

When we reverse search this image we find a bunch of pages that contain the photo, from a variety of sites. One of the sites returned is Reddit. Reddit is a site that is famous for sharing these sorts of photos, but it also has a reputation for having a user base that is very good at spotting fake photos.

When we go to the Reddit page we find there is an argument there over whether the photo is fake or not. But again, Reddit is not our source here — we need to go further upstream. So we click the link in the Reddit forum that says it’s real and get taken to an article where they actually talk to the photographer:

That brings us to one of the original stories about this photo:

Now we could stop here, and just read the headline. But all good fact-checkers know that headlines lie. So we read the article down to the bottom:

For this particular shot, Singson says, “Always trying to be creative, I thought it would be pretty cool (hot!) to take a lava pic with my shoes and tripod on fire while photographing lava.”

This may be a bit pedantic — but I still don’t know if this was staged. Contrary to the headline the photographer doesn’t say lava made his shoes catch on fire. He says he wanted to take a picture of himself with his shoes on fire while standing on lava

So did his shoes catch on fire, or did he set them on fire? I do notice at the bottom of this page though that this is just a retelling of an article published elsewhere — it’s not this publication who talked to the photographer! It’s a similar situation to what we saw in an earlier chapter, where The Blaze was simply retelling a story that was investigated by The Daily Dot.

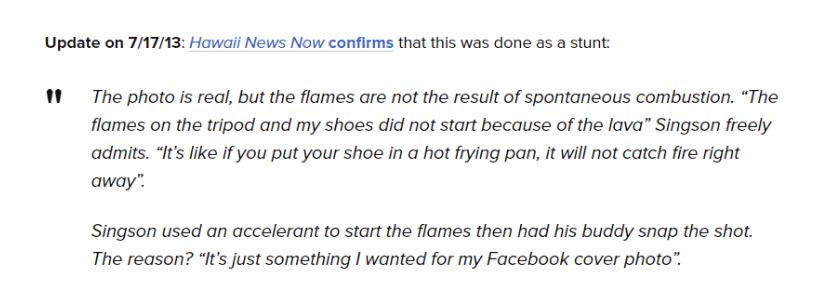

In webspeak, “via” means you learned of a story or photo from someone else. In other words, we still haven’t gotten to the source. So we lumber upstream once again, to the PetaPixel site from whence this came.. When we go upstream to that site, we find an addendum on the original article:

So a local news outfit has confirmed the photographer did use an accelerant. The photograph was staged. Are we done now?

Not quite. You know what the next step is, right?

Go upstream to Hawaii News Now!

So we do that, we click the link, and we find the quote is good. And I like Hawaii News Now for another reason — they are a local news service, and so they know a bit about lava fields. That’s probably why they asked the question no one else seemed to ask: “Is that really possible?”

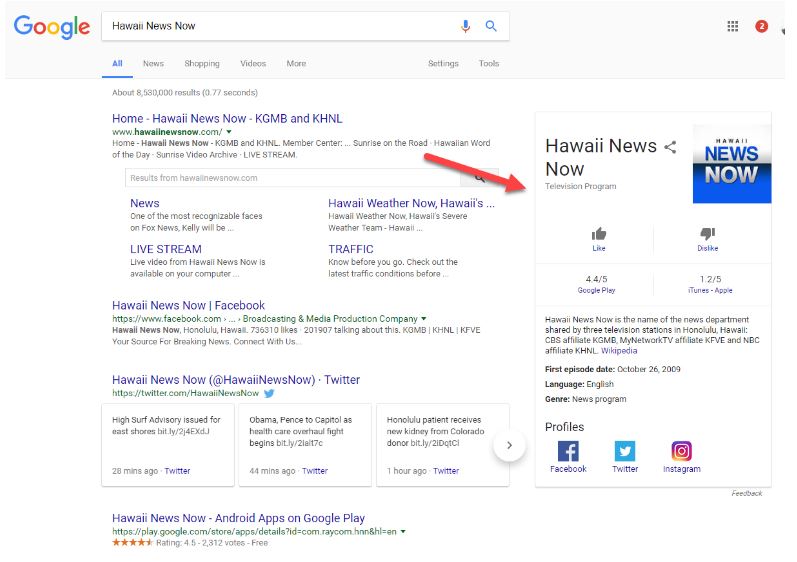

Finally, let’s find out about Hawaii News Now. We start by selecting Hawaii News Now and using our Google search option:

And what we get back is pretty promising: there’s a Google Card that comes up that tells us it’s bona fide local news program from a CBS affiliate in Hawaii.

And honestly, you could stop there. We’ve solved this riddle. The photographer was really on hot lava, which is impressive in itself, but used some accelerant (such as lighter fluid) to set his shoes and tripod on fire. Additionally, the photo was a stunt, and not part of any naturally occurring National Geographic shoot. We’ve traced the story back to its source, found the answer, and got confirmation on the authoritative nature of the source.

We’re sticklers for making absolutely sure of this, so we’re going to go upstream one more time, and click on the Wikipedia link to the article on the Google card to make sure we aren’t missing anything, but we don’t have to make you watch that. We’ll tell you right now it will turn out fine.

In this case at least.