1.5: Raíces de números complejos

- Page ID

- 114163

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Recordemos que si\(z=x+iy\) es un número complejo distinto de cero, entonces se puede escribir en forma polar como

\(z=r(cosθ+isinθ)\)

donde\(r=\sqrt{x^{2}+y^{2}}\) y\(\theta \) es el ángulo, en radianes, desde el eje x positivo hasta el rayo que conecta el origen con el punto\(z\).

Ahora bien, la fórmula de de Moivre establece que si\(z=r(cosθ+isinθ)\) y\(n\) es un entero positivo, entonces

\(z^{n}=r^{n}(cosn\theta +isinn\theta )\)

Dejar\(w\) ser un número complejo. Usar la fórmula de Moivre nos ayudará a resolver la ecuación

\(z^{n}=w\)

para\(z\) cuando\(w\) se da.

Supongamos que\(w=r(cosθ+isinθ)\) y\(z=\rho(cos\psi +isin\psi )\) Entonces la fórmula de Moivre da

\(z^{n}=\rho ^{n}(cosn\psi +isinn\psi )\)

De ello se deduce que

\(\rho ^{n}=r=\left | w \right |\)

por la singularidad de la representación polar y

\(n\Psi =\theta +k(2\pi )\),

donde\(k\) es algún número entero. Así

\(z=\sqrt[n]{r}[cos(\frac{\theta }{n}+\frac{2k\pi }{n})+isin(\frac{\theta }{n}+\frac{2k\pi }{n})]\).

Cada valor de\(k=0,1,2,…,n−1\) da un valor diferente de\(z\). Cualquier otro valor de\(k\) simplemente repite uno de los valores de\(z\) correspondiente a\(k=0,1,2,…,n−1\). Por lo tanto, hay\(n\) exactamente las raíces de un número complejo distinto de cero.

Usando la fórmula de Euler:

\(e^{i\theta }=cos\theta +isin\theta \),

el número complejo también se\(z=r(cos\theta +isin\theta) \\) puede escribir en forma exponencial como

\(z=re^{i\theta }\)

Por lo tanto, las raíces\(n\) th de un número complejo distinto de cero también se\(z≠0\) pueden expresar como

\ (\ begin {eqnarray}\ label {expform}

z=\ sqrt [n] {r}\;\ mbox {exp}\ izquierda [i\ left (\ frac {\ theta} {n} +\ frac {2k\ pi} {n}\ derecha)\ derecha]

\ end {eqnarray}\)

donde\(k=0,1,2,...,n-1\).

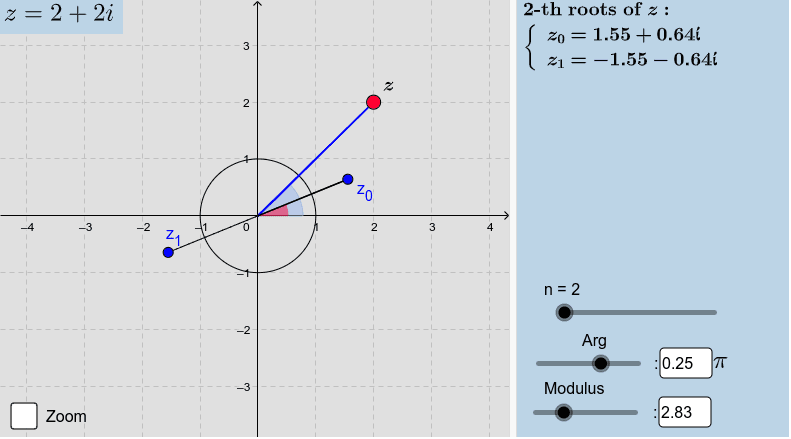

El applet a continuación muestra una representación geométrica de las raíces\(n\) th de un número complejo, hasta\(n=10\). Arrastre el punto rojo alrededor para cambiar el valor de\(z\) o arrastre los controles deslizantes.

- Código

-

Ingresa el siguiente script en GeoGebra para explorarlo tú mismo y hacer tu propia versión. El símbolo # indica comentarios.

#Complex number Z = 1 + ί #Modulus of Z r = abs(Z) #Angle of Z theta = atan2(y(Z), x(Z)) #Number of roots n = Slider(2, 10, 1, 1, 150, false, true, false, false) #Plot n-roots nRoots = Sequence(r^(1 / n) * exp( ί * ( theta / n + 2 * pi * k / n ) ), k, 0, n-1)

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{1}\)

A partir de la forma exponencial (1) de las raíces, muestran que todas las raíces\(n\) th se encuentran en el círculo\(\left | z \right |=\sqrt[n]{r}\) alrededor del origen y están igualmente espaciadas cada\(\frac{2\pi }{n}\) radianes, comenzando por el argumento\(\frac{\theta }{n}\).