20.7: Área de triángulos sólidos

- Page ID

- 114529

Dejar\(a=BC\) y\(h_A\) ser la altitud desde\(A\) adentro\(\triangle ABC\). Entonces

\(\text{area }(\blacktriangle ABC)=\tfrac12\cdot a\cdot h_A.\)

- Prueba

-

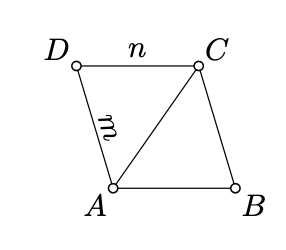

Dibuja la línea\(m\) a través\(A\) que es paralela\((BC)\) y la línea a\(n\) través de\(C\) paralela a\((AB)\). Tenga en cuenta que las líneas\(m\) y no\(n\) son paralelas; denotan por\(D\) su punto de intersección. Por construcción,\(\square ABCD\) es un paralelogramo.

Tenga en cuenta que\(\blacksquare ABCD\) admite una subdivisión en\(\blacktriangle ABC\) y\(\blacktriangle CDA\). Por lo tanto,\[\text{area }(\blacksquare ABCD) = \text{area }(\blacktriangle ABC) + \text{area }(\blacktriangle CDA)\]

Dado que\(\square ABCD\) es un paralelogramo, Lemma 7.5.1 implica que

\(AB=CD \quad \text{and} \quad BC=DA.\)

Por lo tanto, por la condición de congruencia SSS, tenemos\(\triangle ABC\cong\triangle CDA\). En particular

\(\text{area }(\blacktriangle ABC) = \text{area }(\blacktriangle CDA).\)

De arriba y de la Proposición 20.6.1, obtenemos que

\(\begin{aligned} \text{area }(\blacktriangle ABC) &=\tfrac12\cdot\text{area }(\blacksquare ABCD)= \\ &=\tfrac12\cdot h_A\cdot a\end{aligned}\)

Dejar\(h_A\),\(h_B\), y\(h_C\) denotar las altitudes de\(\triangle ABC\) desde vértices\(A\),\(B\) y\(C\) respectivamente. Tenga en cuenta que del teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\), se deduce que

\(h_A\cdot BC=h_B\cdot CA=h_C\cdot AB.\)

Dar una prueba de esta declaración sin usar área.

- Insinuación

-

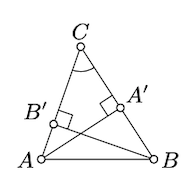

Sin pérdida de generalidad, podemos suponer que los ángulos\(ABC\) y\(BCA\) son agudos.

Dejar\(A'\) y\(B'\) denotar los puntos del pie de\(A\) y\(B\) sobre\((BC)\) y\((AC)\) respectivamente. Tenga en cuenta que\(h_A = AA'\) y\(h_B = BB'\).

Tenga en cuenta que\(\triangle AA'C \sim \triangle BB'C\); de hecho el ángulo a\(C\) es compartido y los ángulos en\(A'\) y\(B'\) son correctos. En particular\(\dfrac{AA'}{BB'} = \dfrac{AC}{BC}\) o, de manera equivalente,\(h_A \cdot BC = h_B \cdot AC\).

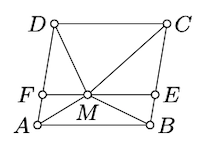

Supongamos que\(M\) se encuentra dentro del paralelogramo\(ABCD\); es decir,\(M\) pertenece al paralelogramo sólido\(\blacksquare ABCD\), pero no se encuentra en sus lados. Demostrar que

\(\text{area }(\blacktriangle ABM)+\text{area }(\blacktriangle CDM) =\tfrac12\cdot \text{area }(\blacksquare ABCD).\)

- Insinuación

-

Dibuja la\(\ell\) línea\(M\) paralela a\([AB]\) y\([CD]\); se\(\blacksquare ABCD\) subdivide en dos paralelogramos sólidos que se denotarán por\(\blacksquare ABEF\) y\(\blacksquare CDFE\). En particular,

\(\text{area } (\blacksquare ABCD) = \text{area } (\blacksquare ABEF) + \text{area } (\blacksquare CDFE)\).

Por la Proposición 20.6.1 y Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) obtenemos que

\(\begin{array} {l} {\text{area } (\blacktriangle ABM) = \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \text{area } (\blacksquare ABEF),} \\ {\text{area } (\blacktriangle CDM) = \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \text{area } (\blacksquare CDFE)} \end{array}\)

y de ahí el resultado.

Supongamos que las diagonales de un cuadriángulo no degenerado se\(ABCD\) cruzan en el punto\(M\). Demostrar que

\(\text{area }(\blacktriangle ABM)\cdot\text{area }(\blacktriangle CDM) = \text{area }(\blacktriangle BCM)\cdot\text{area }(\blacktriangle DAM).\)

- Insinuación

-

Dejar\(h_A\) y\(h_C\) denotar las distancias desde\(A\) y\(C\) hacia la línea\((BD)\) respectivamente. Según el teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\),

\(\text{area }(\blacktriangle ABM) = \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot h_A \cdot BM\);\(\text{area }(\blacktriangle BCM) = \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot h_C \cdot BM\);

\(\text{area }(\blacktriangle CDM) = \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot h_C \cdot DM\);\(\text{area }(\blacktriangle ABM) = \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot h_A \cdot DM\).Por lo tanto

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {\text{area } (\blacktriangle ABM) \cdot \text{area } (\blacktriangle CDM)} & = & {\dfrac{1}{4} \cdot h_A \cdot h_C \cdot DM \cdot BM =} \\ {} & = & {\text{area } (\blacktriangle BCM) \cdot \text{area } (\blacktriangle DAM)} \end{array}\)

\(r\)Sea el inradio de\(\triangle ABC\) y\(p\) sea su semiperímetro; es decir,\(p=\tfrac12\cdot(AB+BC+CA)\). Demostrar que

\(\text{area }(\blacktriangle ABC)=p\cdot r.\)

- Insinuación

-

\(I\)Déjese ser el incenter de\(\triangle ABC\). Tenga en cuenta que se\(\blacktriangle ABC\) puede subdividir en\(\blacktriangle IAB, \blacktriangle IBC\) y\(\blacktriangle ICA\).

Queda por aplicar el Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) a cada uno de estos triángulos y resumir los resultados.

Mostrar que cualquier conjunto poligonal admite una subdivisión en una colección finita de triángulos sólidos y un conjunto degenerado. Concluimos que para cualquier conjunto poligonal, su área está definida de manera única.

- Insinuación

-

Fijar un conjunto poligonal\(\mathcal{P}\). Sin pérdida de generalidad podemos suponer que\(\mathcal{P}\) es una unión de una colección finita de triángulos sólidos. Corta\(\mathcal{P}\) a lo largo de las extensiones de los lados de todos los triángulos, se\(\mathcal{P}\) subdivide en polígonos convexos. Cortar cada polígono por diagonales de un vértice produce una subdivisión en triángulos sólidos.