6.2: La irracionalidad de √2

- Page ID

- 117911

En esta sección probaremos uno de los teoremas más antiguos e importantes en matemáticas:\(\sqrt{2}\) es irracional (ver Teorema 6.19). Primero, necesitamos saber qué significa esto.

Definición 6.18. Vamos\(r\in\mathbb{R}\).

- Decimos que\(r\) es racional si\(r=\frac{m}{n}\), donde\(m,n\in\mathbb{Z}\) y\(n\neq 0\).

- En contraste, decimos que\(r\) es irracional si no es racional.

Los pitagóricos eran una antigua sociedad secreta que seguía a su líder espiritual: Pitágoras de Samos (c. 570—495 a. C.). Los pitagóricos creían que el camino hacia la realización espiritual y hacia una comprensión del universo era a través del estudio de las matemáticas. Creían que todas las matemáticas, la música y la astronomía podían describirse a través de números enteros y sus proporciones. En términos matemáticos modernos creían que todos los números son racionales. A Pitágoras se le atribuye el dicho: “La beatitud es el conocimiento de la perfección de los números del alma”. Y su lema era “Todo es número”.

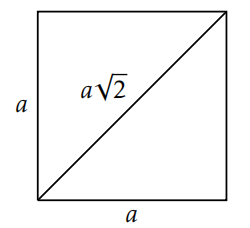

Así quedaron atónitos cuando uno de los suyos —Hippasus of Metapontum (c. siglo V a. C.) —descubrió que el lado y la diagonal de un cuadrado son inconmensurables. Es decir, la relación entre la longitud de la diagonal y la longitud del lado es irracional. En efecto, si el lado del cuadrado tiene longitud\(a\), entonces la diagonal tendrá longitud\(a\sqrt{2}\); la relación es\(\sqrt{2}\) (ver Figura 6.1).

En la Sección 5.1, dimos por sentado que eso\(\sqrt{2}\) era irracional. Ahora demostramos este hecho. Considera usar una prueba por contradicción. Supongamos que existen\(m,n\in\mathbb{Z}\) tal que\(n\ne 0\) y\(\sqrt{2}=\frac{m}{n}\). ¿Hay un número impar o par de factores de 2 en cada lado de esta ecuación? ¿Su conclusión viola el Teorema Fundamental de la Aritmética (Teorema 6.17)?

Teorema 6.19. El número real\(\sqrt{2}\) es irracional.

Como cabría esperar, los pitagóricos no estaban contentos con este descubrimiento. Cuenta la leyenda que Hipasus fue expulsado de los pitagóricos y quizás fue ahogado en el mar. Irónicamente, este resultado, que tanto enfureció a los pitagóricos, es probablemente su mayor contribución a las matemáticas: el descubrimiento de números irracionales.

A ver si se puede generalizar la técnica en la prueba del Teorema 6.19 para probar los dos teoremas siguientes.

Teorema 6.20. Dejar\(p\) ser un número primo. Entonces\(\sqrt{p}\) es irracional.

Teorema 6.21. Dejar\(p\) y\(q\) ser primos distintos. Entonces\(\sqrt{pq}\) es irracional.

Problema 6.22. Afirma una generalización del Teorema 6.21 y describe brevemente cómo iría su prueba. Ser lo más general posible.

Es importante señalar que no todos los números irracionales positivos son iguales a la raíz cuadrada de algún número natural. Por ejemplo,\(\pi\) es irracional, pero no es igual a la raíz cuadrada de un número natural.