26.4: A.4- Graficar una función definida por partes

- Page ID

- 117813

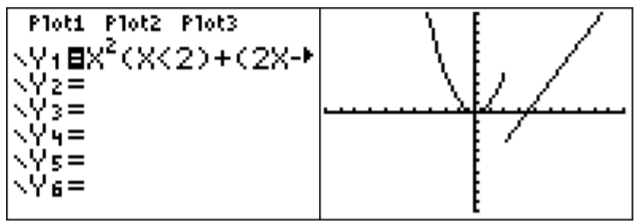

Supongamos que desea graficar la función definida por partes

\[f(x)= \begin{cases}x^{2}, & x<2 \\ 2 x-7, & x \geq 2\end{cases} \nonumber \]

Ir al menú. Necesitamos ingresar a la función de la siguiente manera:

\[y=x^2(x<2)+(2x-7)(x\geq 2) \nonumber \]

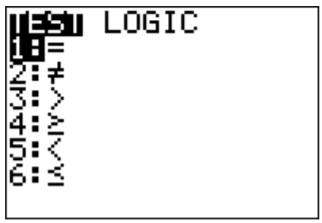

Las únicas entradas nuevas están en los signos de desigualdad, a los que se puede acceder a través del menú “TEST” (\(\boxed{\text{2nd}}\)\(\boxed{\text{math}}\)).

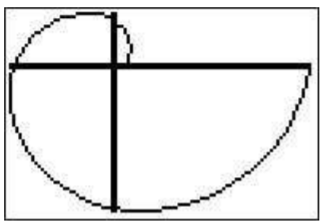

Por lo tanto, presionamos las teclas:\(\boxed{\text{X,T,}\theta,n}\)\(\boxed{x^2}\)\(\boxed{\text{(}}\)\(\boxed{\text{X,T,}\theta,n}\)\(\boxed{\text{2nd}}\)\(\boxed{\text{math}}\)\(\boxed{\text{5}}\)\(\boxed{\text{2}}\)\(\boxed{\text{)}}\)\(\boxed{\text{+}}\)\(\boxed{\text{(}}\)\(\boxed{\text{2}}\)\(\boxed{\text{X,T,}\theta,n}\)\(\boxed{\text{-}}\)\(\boxed{\text{7}}\)\(\boxed{\text{)}}\)\(\boxed{\text{(}}\)\(\boxed{\text{X,T,}\theta,n}\)\(\boxed{\text{2nd}}\)\(\boxed{\text{math}}\)\(\boxed{\text{4}}\)\(\boxed{\text{2}}\)\(\boxed{\text{)}}\)\(\boxed{\text{enter}}\). El gráfico se muestra a la derecha:

El significado de\(y=(x<2)\) como función es que es igual a\(1\) cuando es verdad y\(0\) cuando es falso. En otras palabras, la expresión\((x<2)\) es\(1\) cuándo\(x<2\) y de\(0\) otra manera. Puedes usar esta idea para graficar funciones más complicadas. Por ejemplo para ingresar\(x+2\) para\(0<x<3\) usted podría ingresar\((x+2)(0<x)(x<3)\).

Nota: Al graficar funciones definidas por partes, la gráfica a veces es diferente de lo que se espera. Consulte la sección de errores comunes para interpretar la gráfica resultante a continuación.

Graficar con coordenadas polares

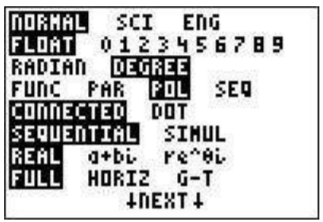

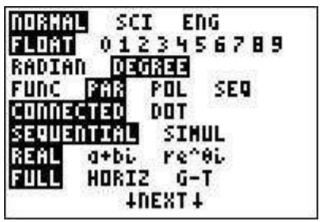

Supongamos que quiere graficar la curva\(r=\theta+\sin\theta\). Prensa\(\boxed{\text{mode}}\). En la cuarta línea resalte 'Pol' y presiona\(\boxed{\text{enter}}\) (asegúrate de que también en modo radián)

y prensa\(\boxed{y=}\). Tu menú tendrá una lista\(r_1, r_2,...\). Después del\(r_1\) tipo\(\boxed{\text{X,T,}\theta,n}\)\(\boxed{\text{+}}\)\(\boxed{\sin}\)\(\boxed{\text{X,T,}\theta,n}\)\(\boxed{\text{)}}\). Después para ver el tipo de gráfico\(\boxed{\text{graph}}\). Es posible que tenga que ajustar su ventana (ajuste de zoom) para ver la espiral resultante.

Graficar con coordenadas paramétricas

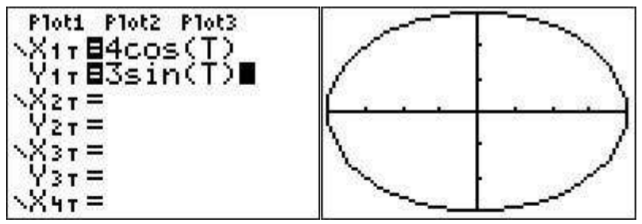

Supongamos que desea graficar la curva dada por\(y(t)=3\sin(t), x(t)=4\cos(t)\). Primero tenemos que ajustar el modo a modo paramétrico: presione\(\boxed{\text{mode}}\) y resalte 'PAR' en la cuarta línea y presione\(\boxed{\text{enter}}\).

Ahora ve a la pantalla gráfica. Verás una lista que comienza con X\(_{1T}\) e Y\(_{1T}\). A la derecha del\(_{1T}\) tipo X\(\boxed{\text{4}}\)\(\boxed{\cos}\)\(\boxed{\text{X,T,}\theta,n}\) y a la derecha del\(_{1T}\) tipo\(\boxed{\text{3}}\)\(\boxed{\sin}\)\(\boxed{\text{X,T,}\theta,n}\) Y. Después para ver la gráfica presione\(\boxed{\text{graph}}\). Es posible que necesite\(\boxed{\text{zoom}}\)\(\boxed{\text{0}}\) (zoomfit) para ver la elipse resultante. (Además, tenga en cuenta que la escala puede ser engañosa, es posible que desee\(\boxed{\text{zoom}}\)\(\boxed{\text{5}}\) para una comprensión más clara de la gráfica).