5.7: Intermedios Reactivos - Carbocationes

- Page ID

- 76294

Objetivo de aprendizaje

- describir la estructura y las estabilidades relativas de los carbocationes

Carbocationes y su estabilidad

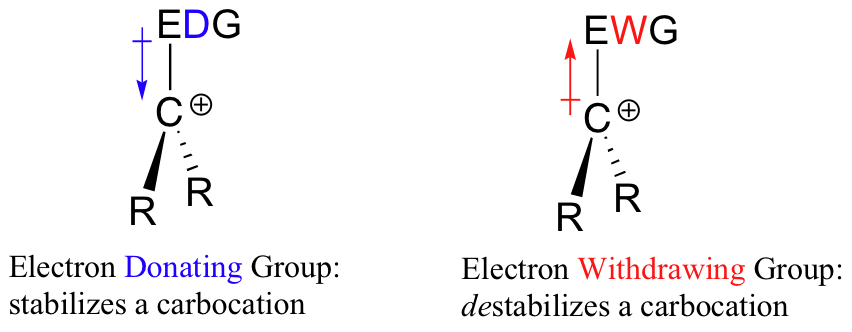

Un carbocatión es un ion con un átomo de carbono cargado positivamente. A el carbocatión es muy pobre en electrones, y así todo lo que dona densidad electrónica al centro de la pobreza electrónica ayudará a estabilizarlo. Por el contrario, un carbocatión será desestabilizado por un grupo aceptor de electrones.

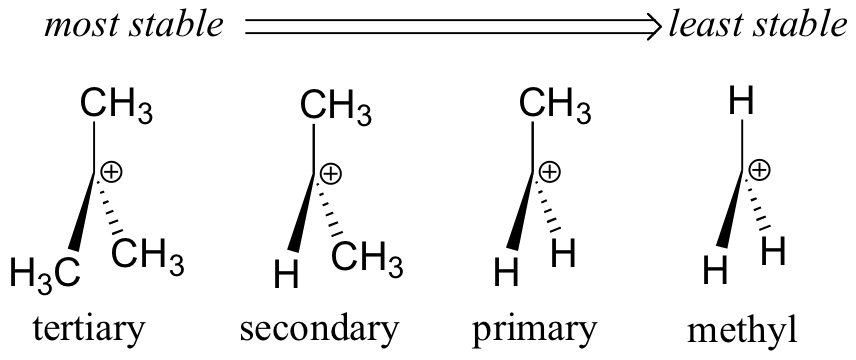

Los grupos alquilo son donantes de electrones y estabilizantes de carbocationes porque los electrones alrededor de los vecinos los carbonos son atraídos hacia la carga positiva cercana, reduciendo así ligeramente la pobreza electrónica del carbono cargado positivamente. Lo que esto significa es que, en general, más carbocationes sustituidos son más estables: un carbocatión terc-butilo, por ejemplo, es más estable que un carbocatión isopropilo. Los carbocationes primarios son altamente inestables y no suelen observarse como intermedios de reacción; los carbocationes de metilo son aún menos estables.

No es exacto decir, sin embargo, que los carbocationes con mayor sustitución son siempre más estables que aquellos con menos sustitución. Así como los grupos donadores de electrones pueden estabilizar un carbocatión, los grupos aceptores de electrones actúan para desestabilizar los carbocationes. Los grupos carbonilo son extractores de electrones por efectos inductivos, debido a la polaridad del doble enlace C=O. Es posible demostrar en laboratorio (ver sección 16.1D) que el carbocatión A a continuación es más estable que el carbocatión B, aunque A es un carbocatión primario y B es secundario.

The difference in stability can be explained by considering the electron-withdrawing inductive effect of the ester carbonyl. Recall that inductive effects - whether electron-withdrawing or donating - are relayed through covalent bonds and that the strength of the effect decreases rapidly as the number of intermediary bonds increases. In other words, the effect decreases with distance. In species B the positive charge is closer to the carbonyl group, thus the destabilizing electron-withdrawing effect is stronger than it is in species A.

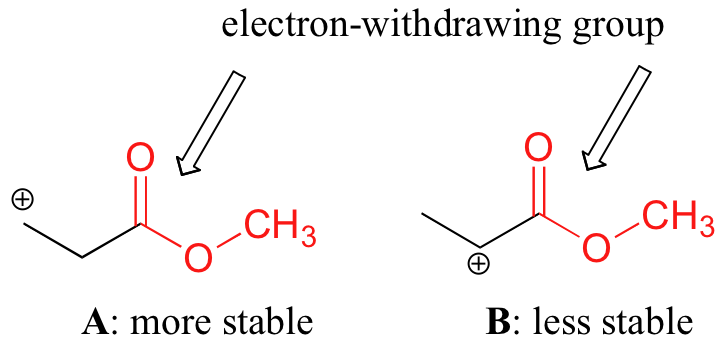

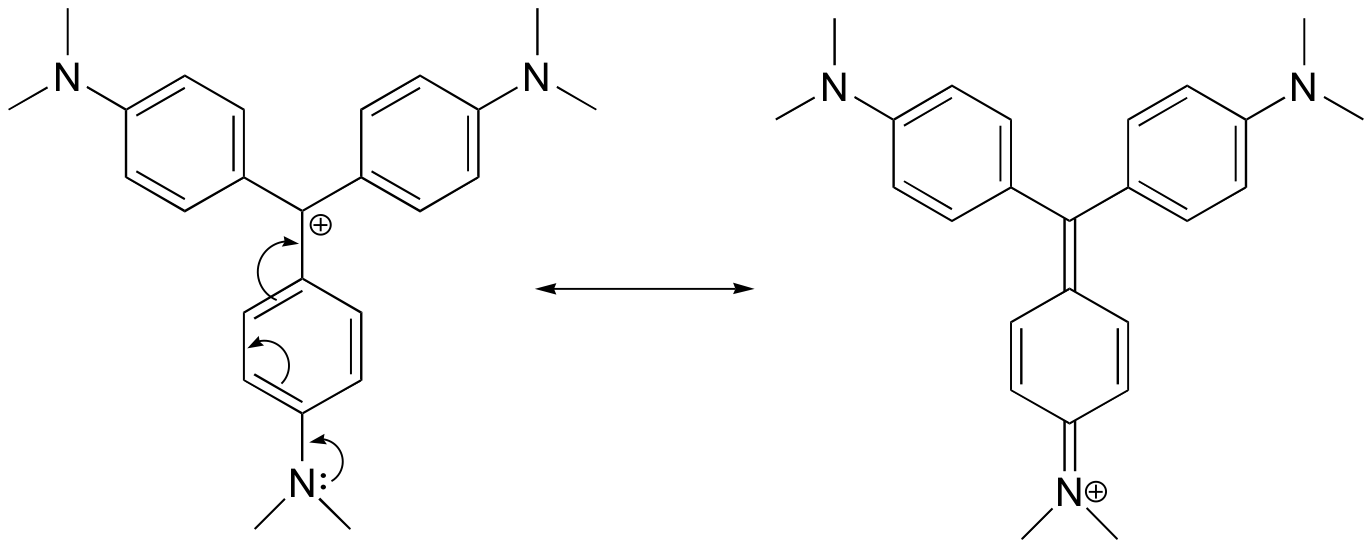

Stabilization of a carbocation can also occur through resonance effects, and as we have already discussed in the acid-base chapter, resonance effects as a rule are more powerful than inductive effects. Consider the simple case of a benzylic carbocation:

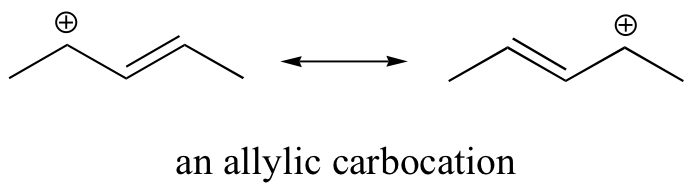

This carbocation is comparatively stable. In this case, electron donation is a resonance effect. Three additional resonance structures can be drawn for this carbocation in which the positive charge is located on one of three aromatic carbons. The positive charge is not isolated on the benzylic carbon, rather it is delocalized around the aromatic structure: this delocalization of charge results in significant stabilization. As a result, benzylic and allylic carbocations (where the positively charged carbon is conjugated to one or more non-aromatic double bonds) are significantly more stable than even tertiary alkyl carbocations.

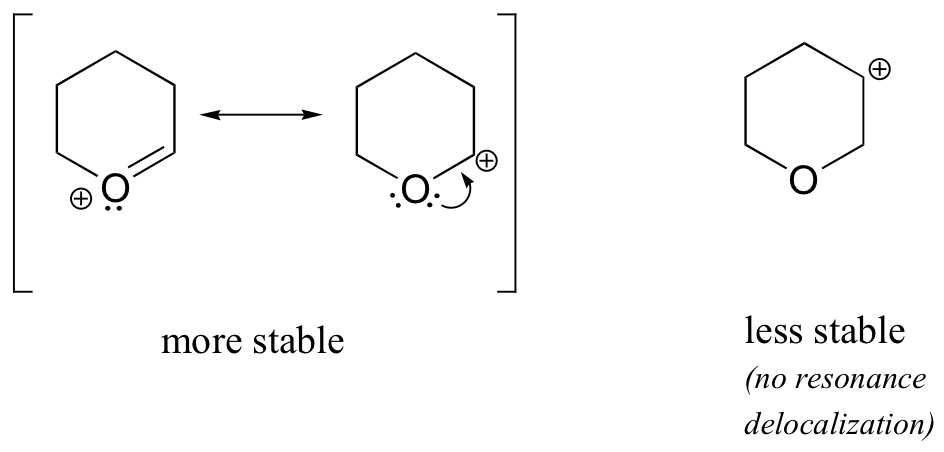

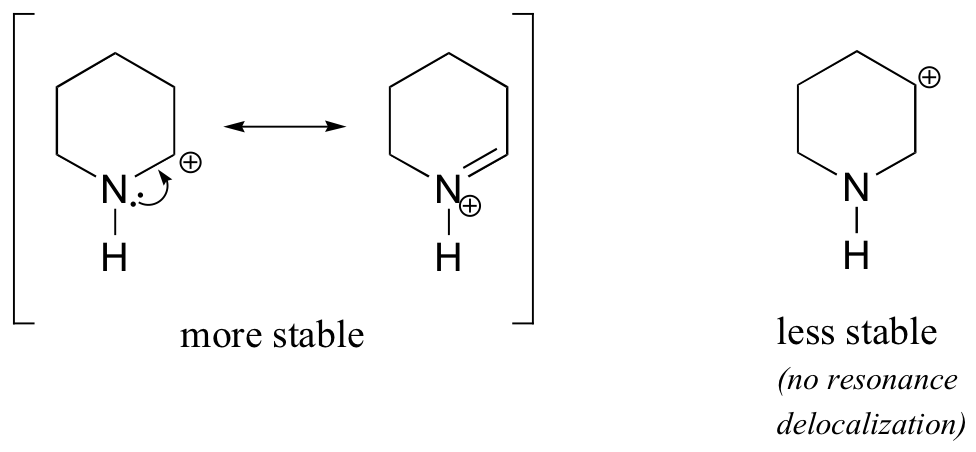

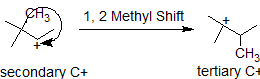

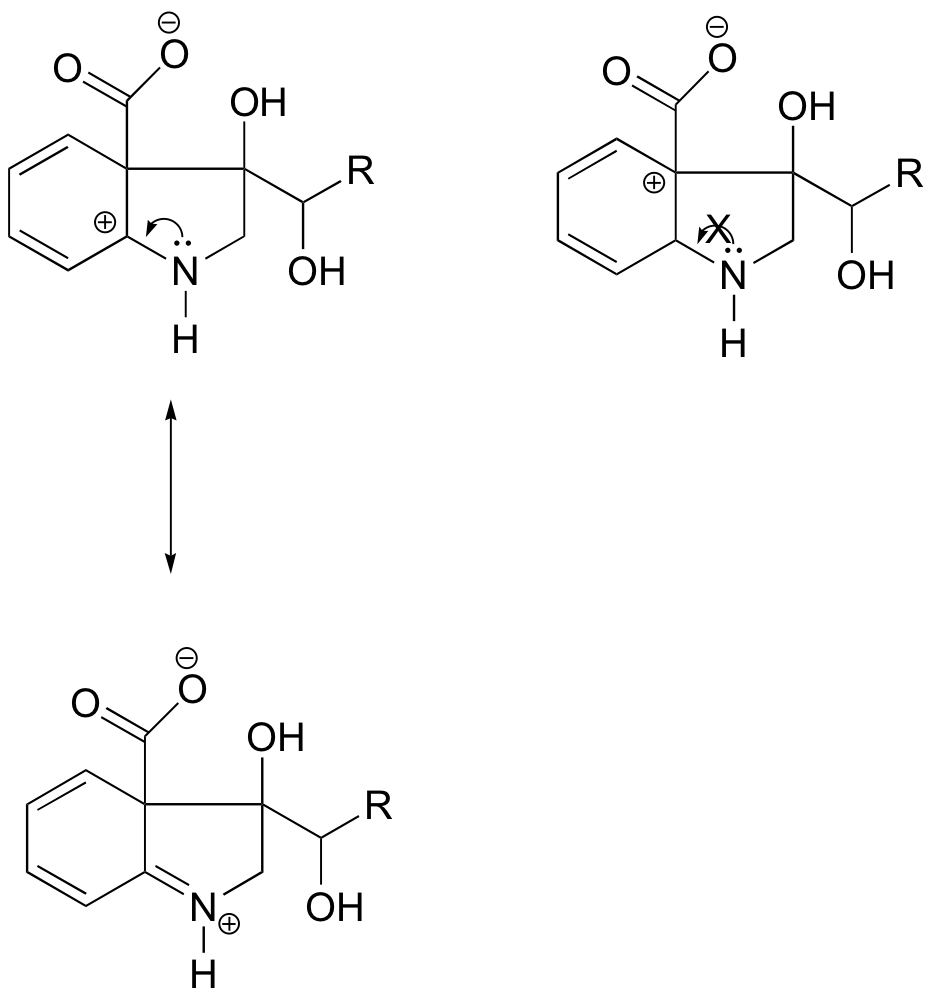

Because heteroatoms such as oxygen and nitrogen are more electronegative than carbon, you might expect that they would by definition be electron withdrawing groups that destabilize carbocations. In fact, the opposite is often true: if the oxygen or nitrogen atom is in the correct position, the overall effect is carbocation stabilization. This is due to the fact that although these heteroatoms are electron withdrawing groups by induction, they are electron donating groups by resonance, and it is this resonance effect which is more powerful. (We previously encountered this same idea when considering the relative acidity and basicity of phenols and aromatic amines in section 7.4). Consider the two pairs of carbocation species below:

In the more stable carbocations, the heteroatom acts as an electron donating group by resonance: in effect, the lone pair on the heteroatom is available to delocalize the positive charge. In the less stable carbocations the positively-charged carbon is more than one bond away from the heteroatom, and thus no resonance effects are possible. In fact, in these carbocation species the heteroatoms actually destabilize the positive charge, because they are electron withdrawing by induction.

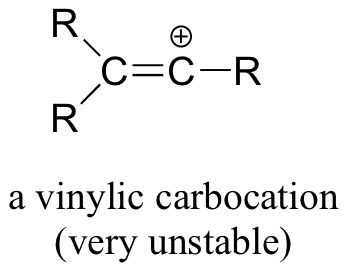

Finally, vinylic carbocations, in which the positive charge resides on a double-bonded carbon, are very unstable and thus unlikely to form as intermediates in any reaction.

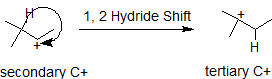

Carbocation Rearrangements

Carbocations typically undergo rearrangement reactions from less stable structures to equally stable or more stable ones with rate constants in excess of 109/sec. This fact complicates synthetic pathways to many compounds, so it is important to look for carbocation rearrangements anytime they are formed. It is possible for either a neighboring hydrogen atom or methyl group to shift to the carbocation to create a more stable intermediate. In the 1,2-hydride shift shown below, the secondary carbocatin rearranges to a more stable tertiary carbocation. The numbers, 1,2- refer to the vicinal location of the rearrangement, not the nomenclature numbers.

In this next example, the methyl group shifts to stabilize the carbocation.

Exercise

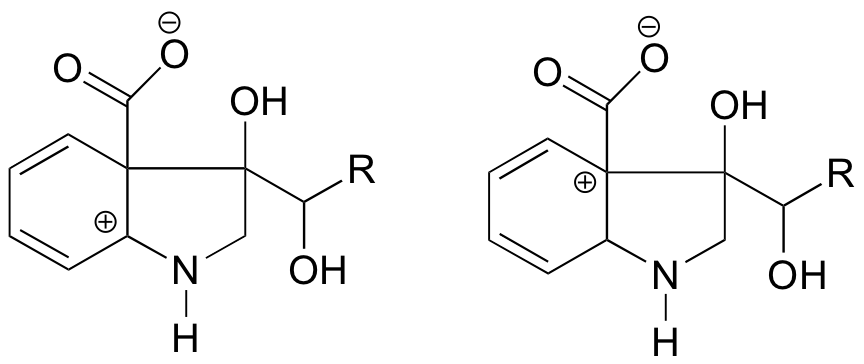

- In which of the structures below is the carbocation expected to be more stable? Explain.

2. Draw a resonance structure of the crystal violet cation in which the positive charge is delocalized to one of the nitrogen atoms.

State which carbocation in each pair below is more stable, or if they are expected to be approximately equal. Explain your reasoning.

- Answer

-

1. In the carbocation on the left, the positive charge is located in a position relative to the nitrogen such that the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen can be donated to fill the empty orbital. This is not possible for the carbocation species on the right.

2.

3.

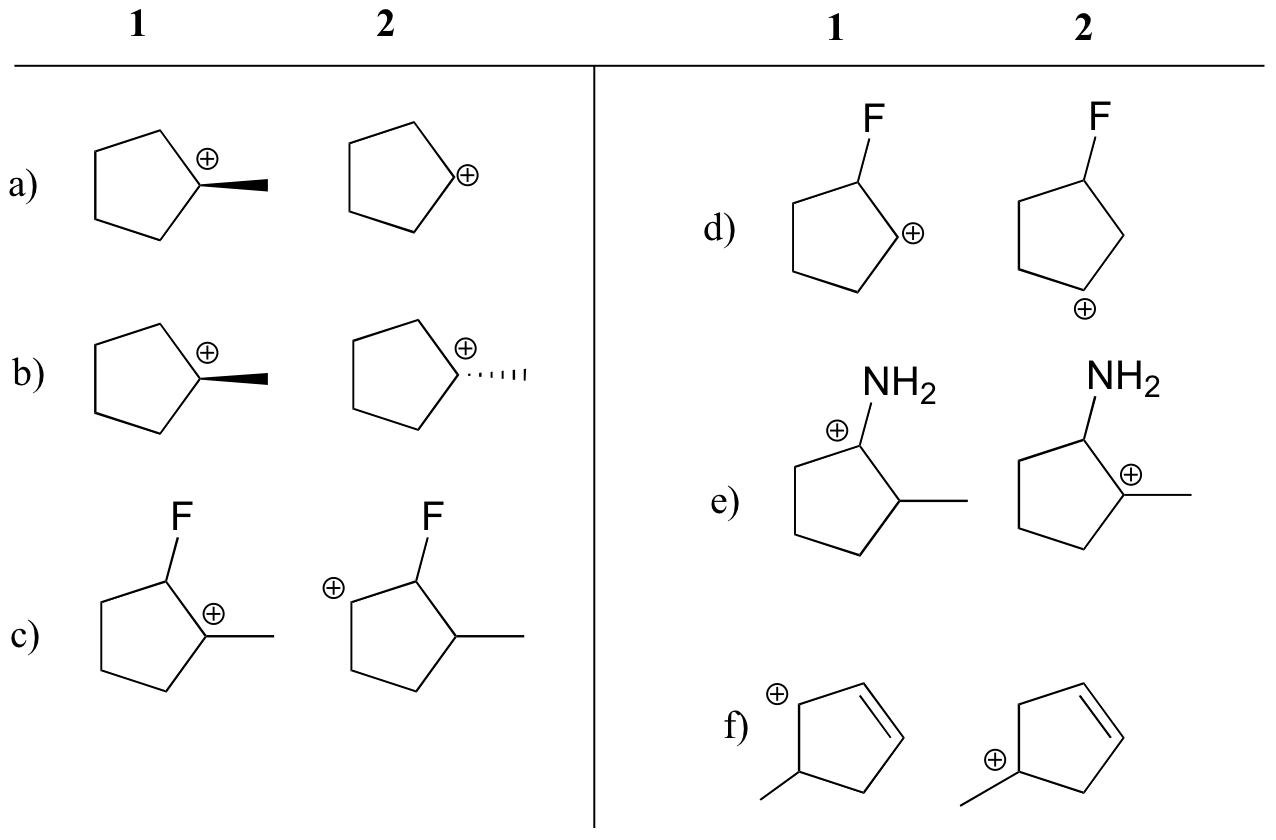

a) 1 (tertiary vs. secondary carbocation)

b) equal

c) 1 (tertiary vs. secondary carbocation)

d) 2 (positive charge is further from electron-withdrawing fluorine)

e) 1 (lone pair on nitrogen can donate electrons by resonance)

f) 1 (allylic carbocation – positive charge can be delocalized to a second carbon)

History

The history of carbocations dates back to 1891 when G. Merling[8] reported that he added bromine to tropylidene (cycloheptatriene) and then heated the product to obtain a crystalline, water-soluble material, \(C_7H_7Br\). He did not suggest a structure for it; however, Doering and Knox[9] convincingly showed that it was tropylium (cycloheptatrienylium) bromide. This ion is predicted to be aromatic by Hückel's rule.

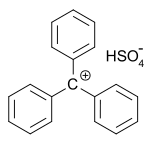

In 1902, Norris and Kehrman independently discovered that colorless triphenylmethanol gives deep-yellow solutions in concentrated sulfuric acid. Triphenylmethyl chloride similarly formed orange complexes with aluminium and tin chlorides. In 1902, Adolf von Baeyer recognized the salt-like character of the compounds formed.

He dubbed the relationship between color and salt formation halochromy, of which malachite green is a prime example.

Carbocations are reactive intermediates in many organic reactions. This idea, first proposed by Julius Stieglitz in 1899,[10] was further developed by Hans Meerwein in his 1922 study[11][12] of the Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement. Carbocations were also found to be involved in the \(S_N1\) reaction, the \(E1\0 reaction, and in rearrangement reactions such as the Whitmore 1,2 shift. The chemical establishment was reluctant to accept the notion of a carbocation and for a long time the Journal of the American Chemical Society refused articles that mentioned them.

The first NMR spectrum of a stable carbocation in solution was published by Doering et al.[13] in 1958. It was the heptamethylbenzenium ion, made by treating hexamethylbenzene with methyl chloride and aluminium chloride. The stable 7-norbornadienyl cation was prepared by Story et al. in 1960[14] by reacting norbornadienyl chloride with silver tetrafluoroborate in sulfur dioxide at −80 °C. The NMR spectrum established that it was non-classically bridged (the first stable non-classical ion observed).

In 1962, Olah directly observed the tert-butyl carbocation by nuclear magnetic resonance as a stable species on dissolving tert-butyl fluoride in magic acid. The NMR of the norbornyl cation was first reported by Schleyer et al.[15] and it was shown to undergo proton-scrambling over a barrier by Saunders et al.[16]

References

- Hansjörg Grützmacher, Christina M. Marchand (1997), "Heteroatom stabilized carbenium ions", Coordination Chemistry Reviews, volume 163, pages 287-344. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(97)00043-X

- Gold Book definition carbonium ion HTML

- George A. Olah (1972), "Stable carbocations. CXVIII. General concept and structure of carbocations based on differentiation of trivalent (classical) carbenium ions from three-center bound penta- of tetracoordinated (nonclassical) carbonium ions. Role of carbocations in electrophilic reactions." Journal of the American Chemical Society, volume 94, issue 3, pages 808–820 doi:10.1021/ja00758a020

- Organic chemistry 5th Ed. John McMurry ISBN 0-534-37617-7

- Organic Chemistry, Fourth Edition Paula Yurkanis Bruice ISBN 0-13-140748-1

- Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart; Wothers, Peter (2001). Organic Chemistry (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850346-0.

- Organic Chemistry by Marye Anne Fox and James K. Whitesell ISBN 0-7637-0413-X

- Chem. Ber. 24, 3108 1891

- The Cycloheptatrienylium (Tropylium) Ion W. Von E. Doering and L. H. Knox J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1954; 76(12) pp 3203 - 3206; doi:10.1021/ja01641a027

- On the Constitution of the Salts of Imido-Ethers and other Carbimide Derivatives; Am. Chem. J. 21, 101; ISSN: 0096-4085

- H. Meerwein and K. van Emster, Berichte, 1922, 55, 2500.

- Rzepa, H. S.; Allan, C. S. M. (2010). "Racemization of Isobornyl Chloride via Carbocations: A Nonclassical Look at a Classic Mechanism". Journal of Chemical Education 87 (2): 221. Bibcode:2010JChEd..87..221R. doi:10.1021/ed800058c. edit

- The 1,1,2,3,4,5,6-heptamethylbenzenonium ion W. von E. Doering and M. Saunders H. G. Boyton, H. W. Earhart, E. F. Wadley and W. R. Edwards G. Laber Tetrahedron Volume 4, Issues 1-2 , 1958, Pages 178-185 doi:10.1016/0040-4020(58)88016-3

- The 7-norbornadienyl carbonium ion Paul R. Story and Martin Saunders J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1960; 82(23) pp 6199 - 6199; doi:10.1021/ja01508a058

- Stable Carbonium Ions. X.1 Direct Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Observation of the 2-Norbornyl Cation Paul von R. Schleyer, William E. Watts, Raymond C. Fort, Melvin B. Comisarow, and George A. Olah J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1964; 86(24) pp 5679 - 5680; doi:10.1021/ja01078a056

- Stable Carbonium Ions. XI.1 The Rate of Hydride Shifts in the 2-Norbornyl Cation Martin Saunders, Paul von R. Schleyer, and George A. Olah J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1964; 86(24) pp 5680 - 5681; doi:10.1021/ja01078a057

- George A. Olah - Nobel Lecture

- Nuclear magnetic double resonance studies of the dimethylcyclopropylcarbinyl cation. Measurement of the rotation barrier David S. Kabakoff, , Eli. Namanworth J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92 (10), pp 3234–3235 doi:10.1021/ja00713a080

- Stable Carbonium Ions. XVII.1a Cyclopropyl Carbonium Ions and Protonated Cyclopropyl Ketones Charles U. Pittman Jr., George A. Olah J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87 (22), pp 5123–5132 doi:10.1021/ja00950a026

- F.A. Carey, R.J. Sundberg Advanced Organic Chemistry Part A 2nd Ed.

Contributors

Prof. Steven Farmer (Sonoma State University)

Organic Chemistry With a Biological Emphasis by Tim Soderberg (University of Minnesota, Morris)