10.2: Composición de la Atmósfera

- Page ID

- 108756

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)¿Justo qué es el aire?

El aire es fácil de olvidar. Por lo general, no podemos verlo, probarlo, ni olerlo. Sólo podemos sentirlo cuando se mueve. Pero el aire en realidad está hecho de moléculas de muchos gases diferentes. También contiene diminutas partículas de materia sólida.

Gases en Aire

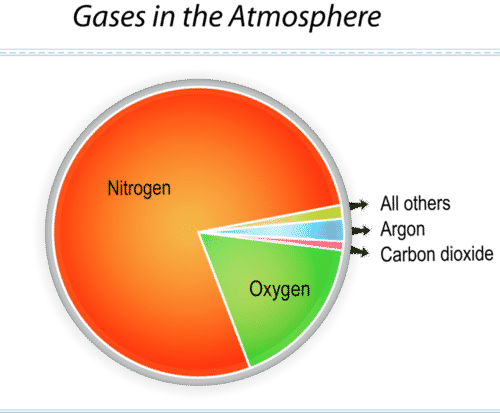

La siguiente figura muestra los principales gases en el aire (Figura a continuación). El nitrógeno y el oxígeno constituyen el 99% del aire. El argón y el dióxido de carbono constituyen gran parte del resto. Estos porcentajes son los mismos casi en todas partes de la atmósfera.

Esta gráfica identifica los gases más comunes en el aire.

El aire también incluye vapor de agua. La cantidad de vapor de agua varía de un lugar a otro. Es por eso que el vapor de agua no está incluido en la figura anterior. Puede constituir hasta el 4% del aire.

Vapor de Agua

La humedad es la cantidad de vapor de agua en el aire. La humedad varía de un lugar a otro. También varía en un mismo lugar de temporada en temporada. En un día de verano en Atlanta, Georgia, la humedad es alta. El aire se siente muy pesado y pegajoso. En un día de invierno en Flagstaff, Arizona, la humedad es baja. El aire aspira la humedad de tu nariz y labios. La humedad puede cambiar rápidamente si entra una tormenta. La humedad puede variar en una distancia corta, como cerca de un lago. Incluso cuando la humedad está en su punto más alto, el vapor de agua constituye aproximadamente 4% de la atmósfera como máximo.

Gases de efecto invernadero

Los gases de efecto invernadero atrapan el calor en la atmósfera. Esto es esencial para que la Tierra tenga una temperatura más moderada. Sin gases de efecto invernadero, las temperaturas nocturnas serían gélidas. Los gases naturales de efecto invernadero incluyen dióxido de carbono, metano, vapor de agua y ozono. Los CFC y algunos otros compuestos artificiales también son gases de efecto invernadero. Las actividades humanas pueden incrementar la cantidad de gases de efecto invernadero, como el dióxido de carbono, en la atmósfera.

Partículas en el Aire

El aire incluye muchas partículas diminutas. Las partículas pueden consistir en polvo, tierra, sal, humo o ceniza. Algunas partículas contaminan el aire y pueden hacer que no sea saludable respirar. Pero tener partículas en el aire es muy importante. Se necesitan partículas diminutas para que el vapor de agua se condense. Sin partículas, el vapor de agua no podría condensarse. Entonces no se podían formar nubes, y la Tierra no tendría lluvia.

Resumen

- Los principales gases atmosféricos son el nitrógeno y el oxígeno. La atmósfera también contiene cantidades menores de otros gases, incluido el dióxido de carbono.

- Los gases de efecto invernadero atrapan el calor en la atmósfera. Estos gases incluyen dióxido de carbono, metano, vapor de agua y ozono.

- No todo en la atmósfera es gas. Las partículas son partículas que son importantes como núcleo de gotas de lluvia y copos de nieve.

Revisar

- ¿Cuáles son los dos principales gases atmosféricos? ¿Cuáles son los gases menores importantes?

- ¿Qué son las partículas? ¿Por qué son importantes?

- ¿Qué es la humedad? ¿Cuánta humedad hay en el aire en un día tremendamente caluroso y húmedo?

Explora más

Utilice el siguiente recurso para responder a las preguntas que siguen.

- ¿Qué contiene la atmósfera?

- ¿Cuánto nitrógeno contiene la atmósfera?

- ¿Cuánto oxígeno contiene la atmósfera?

- ¿Qué hace el ambiente?

- ¿Cuántas capas tiene la atmósfera?

- Enumere las capas de la atmósfera y dos características de cada capa.