7.5.3: Refracción y reflexión- doble refracción

- Page ID

- 51161

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Vamos a examinar ahora qué ocurre cuando hay una discontinuidad de índice y uno de los medios es anisótropo. La superficie de separación la supondremos plana. Para saber si hay o no ondas reflejada y transmitida debemos preguntarlo a las ecMm. Si las hubiera les asignaríamos una superposición de oap:

\[

\begin{aligned}

\mathbf{E}_{i} &=\mathbf{A} e^{i(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{r}-\omega t)} \\

\mathbf{E}_{r} &=\mathbf{R} e^{i\left(\mathbf{k}^{\prime \prime} \cdot \mathbf{r}+\omega^{\prime \prime} t\right)}+\ldots \\

\mathbf{E}_{t} &=\mathbf{T} e^{i\left(\mathbf{k}^{\prime} \cdot \mathbf{r}-\omega^{\prime} t\right)}+\ldots

\end{aligned}

\]

Las condiciones de frontera para los campos no varían porque uno de los medios sea anisótropo. Si las aplicamos obtendremos la igualdad

\[

\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{r}=\mathbf{k}^{\prime} \cdot \mathbf{r}=\mathbf{k}^{\prime \prime} \cdot \mathbf{r} \notag

\]

en \(z=0\) (la interfase),

\[

\begin{aligned}

&k_{x}=k_{x}^{\prime}=k_{x}^{\prime \prime}=n \frac{\omega}{c} \sin \theta \\

&k_{y}=k_{y}^{\prime}=k_{y}^{\prime \prime}=0

\end{aligned}

\]

(la segunda componente se anula por elección de ejes). Es decir, todos los vectores de onda están en el plano de incidencia.

A partir de aquí comienzan las diferencias. En general el módulo del vector de ondas depende de la dirección en un medio anisótropo. Lo que sí sabemos es que el vector de ondas debe estar

- sobre el plano de incidencia

- sobre la superficie de vectores de onda

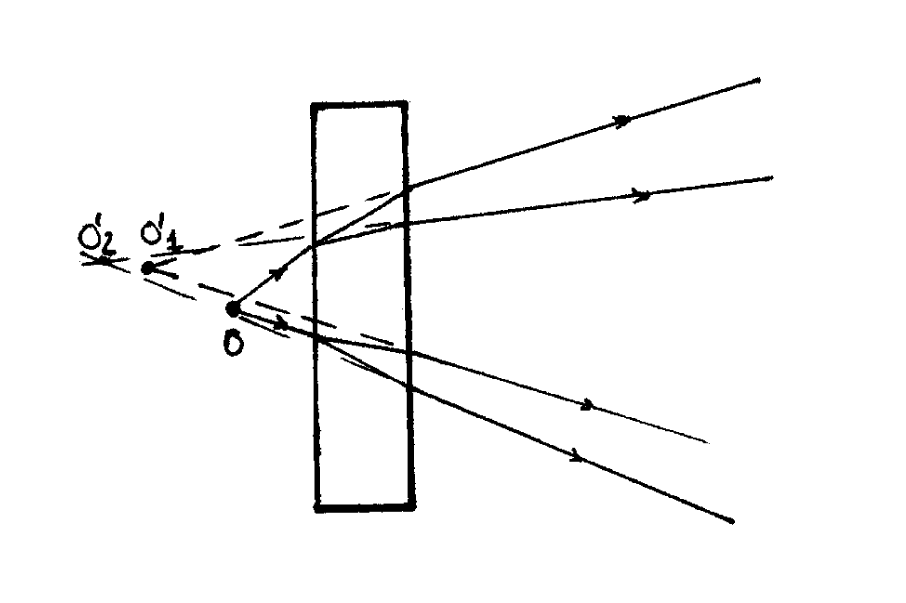

En la figura \(7.5.2.1\) vemos que el vector de ondas de la onda transmitida puede ser uno de los dos que tienen la misma componente \(k_{x}\) y cumplen las dos exigencias planteadas (cortamos las superficies de vectores de onda con el plano de incidencia, obteniendo dos curvas). Utilizando la notación de la figura \(7.5.2.1\)

\[

\begin{aligned}

\left|k_{x}^{\prime}\right|=&\left|\mathbf{k}_{1}^{\prime}\right| \sin \theta_{1}^{\prime}=|\mathbf{k}| \sin \theta=k_{x} \\

\left|\mathbf{k}_{2}^{\prime}\right| \sin \theta_{2}^{\prime} &=|\mathbf{k}| \sin \theta

\end{aligned}

\]

- En general habrá dos ondas refractadas, ya que hay dos vectores de onda que satisfacen las condiciones de frontera \({ }^{3}\). A esta propiedad se la llama doble refracción o birrefringencia. Esto significa que al mirar objetos a través de medios anisótropos se ven dobles.

- Por ser \(\left|\mathbf{k}_{1}^{\prime}\right|\) y \(\left|\mathbf{k}_{2}^{\prime}\right|\) funciones de los respectivos ángulos no hay una ley simple de tipo SNELL. Hay que utilizar las dos últimas ecuaciones que hemos escrito, y las dificultades de cálculo son mucho mayores.

- Interpretación microscópica: la frecuencia de resonancia de los osciladores microscópicas ya no es isótropa. Es como si hubiera 2 medios superpuestos.

No vamos a abordar la especificación de otros parámetros de la onda (fórmulas de FRESNEL, coeficientes de reflexión, etc.). Solamente vamos a comentar un resultado: si concebimos un medio uniáxico cuyo eje óptico esté en el plano de incidencia o sea perpendicular a él se cumple que

- Una onda incidente polarizada linealmente según la dirección perpendicular da lugar a una onda refractada con polarización también perpendicular \(\perp \longrightarrow \perp\)

- \(\|\longrightarrow\|\).

Esta es una circunstancia especial en que ocurre lo mismo que en medios isótropos en cuanto a separación de componentes paralela y perpendicular.

____________________________________________________________________

1. En un medio isótropo la superficie de vectores de onda tenía una sola hoja, de modo que sólo había un vector de onda que cumpliese las condiciones