18.3: Ley Generalizada de Palanca

- Page ID

- 125085

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

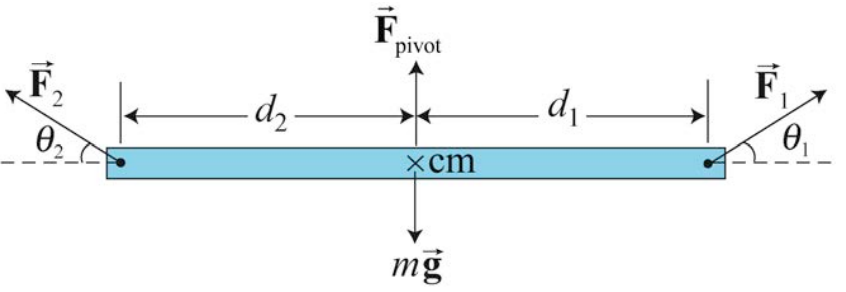

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Podemos extender la Ley de Palanca al caso en el que dos fuerzas externas\(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1} \text { and } \overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2}\) estén actuando sobre la viga pivotada en ángulos\(\theta_{1} \text { and } \theta_{2}\) con respecto a la horizontal como se muestra en la Figura 18.4. A lo largo de esta discusión los ángulos se limitarán al rango\(\left[0 \leq \theta_{1}, \theta_{2} \leq \pi\right]\). Volveremos a descuidar el grosor de la viga y tomar el punto de pivote para que sea el centro de masa.

Las fuerzas se\(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1} \text { and } \overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2}\) pueden descomponer en componentes de vectores separados respectivamente\(\left(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1, \|}, \overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1, \perp}\right) \text { and }\left(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2, \|}, \overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2, \perp}\right)\), donde\(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1, \|} \text { and } \overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2, \|}\) están las proyecciones vectoriales horizontales de las dos fuerzas con respecto a la dirección formada por la longitud de la viga,\(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1, \perp}\) y\(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2, \perp}\) son las proyecciones vectoriales perpendiculares respectivamente a la viga (Figura 18.5), con

\[\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1}=\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1, \|}+\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1, \perp} \nonumber \]

\[\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2}=\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2, \|}+\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2, \perp} \nonumber \]

Los componentes horizontales de las fuerzas son

\[F_{1, \|}=F_{1} \cos \theta_{1} \nonumber \]

\[F_{2, \|}=-F_{2} \cos \theta_{2} \nonumber \]

donde nuestra elección de la dirección horizontal positiva es hacia la derecha. Ninguno de los componentes de fuerza horizontal contribuye al posible movimiento de rotación de la viga. La suma de estas fuerzas horizontales debe ser cero,

\[F_{1} \cos \theta_{1}-F_{2} \cos \theta_{2}=0 \nonumber \]

Las fuerzas de componente perpendiculares son

\[F_{1, \perp}=F_{1} \sin \theta_{1} \nonumber \]

\[F_{2, \perp}=F_{2} \sin \theta_{2} \nonumber \]

donde la dirección vertical positiva es hacia arriba. Los componentes perpendiculares de las fuerzas también deben sumar a cero,

\[F_{\text {pivot }}-m_{b} g+F_{1} \sin \theta_{1}+F_{2} \sin \theta_{2}=0 \nonumber \]

Solo los componentes verticales\(F_{1, \perp} \text { and } F_{2, \perp}\) de las fuerzas externas están involucrados en la ley de la palanca (pero los componentes horizontales deben equilibrarse, como en la Ecuación (18.3.5), para el equilibrio). Entonces la Ley de Palanca se puede extender de la siguiente manera.

Ley de Palanca Generalizada Una viga de longitud l se equilibra sobre un punto de pivote que se coloca directamente debajo del centro de masa de la viga. Supongamos que una fuerza\(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1}\) actúa sobre la viga una distancia\(d_{1}\) a la derecha del punto de pivote. Una segunda fuerza\(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2}\) actúa sobre la viga a una distancia\(d_{2}\) a la izquierda del punto de pivote. El haz permanecerá en equilibrio estático si se satisfacen las dos condiciones siguientes:

1) La fuerza total sobre la viga es cero,

2) El producto de la magnitud de la componente perpendicular de la fuerza con la distancia al pivote es el mismo para cada fuerza,

\[d_{1}\left|F_{1, \perp}\right|=d_{2}\left|F_{2, \perp}\right| \nonumber \]

La Ley de Palanca Generalizada se puede afirmar en forma equivalente,

\[d_{1} F_{1} \sin \theta_{1}=d_{2} F_{2} \sin \theta_{2} \nonumber \]

Ahora mostraremos que la ley de palanca generalizada puede reinterpretarse como la afirmación de que la suma vectorial de los pares alrededor del punto de pivote\(S\) es cero cuando solo hay dos fuerzas que\(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1} \text { and } \overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2}\) actúan sobre nuestra viga como se muestra en la Figura 18.6.

Escojamos la dirección z positiva para señalar fuera del plano de la página y luego el par que señala fuera de la página tendrá un componente z positivo de torque (las rotaciones en sentido antihorario son positivas). De nuestra definición de par sobre el punto de pivote, la magnitud del par debido a la fuerza\(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{1}\) viene dada por

\[\tau_{S, 1}=d_{1} F_{1} \sin \theta_{1} \nonumber \]

De la regla de la mano derecha esto está fuera de la página (en el sentido contrario a las agujas del reloj) por lo que el componente del par es positivo, por lo tanto,

\[\left(\tau_{S, 1}\right)_{z}=d_{1} F_{1} \sin \theta_{1} \nonumber \]

El par debido a\(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{F}}_{2}\) aproximadamente el punto de pivote está en la página (el sentido de las agujas del reloj) y el componente del par es negativo y dado por

\[\left(\tau_{S, 2}\right)_{z}=-d_{2} F_{2} \sin \theta_{2} \nonumber \]

El componente z del par es la suma de los componentes z de los pares individuales y es cero,

\[\left(\tau_{S, \text { total }}\right)_{z}=\left(\tau_{S, 1}\right)_{z}+\left(\tau_{S, 2}\right)_{z}=d_{1} F_{1} \sin \theta_{1}-d_{2} F_{2} \sin \theta_{2}=0 \nonumber \]

que es equivalente a la Ley de Palanca Generalizada, Ecuación (18.3.10),

\[d_{1} F_{1} \sin \theta_{1}=d_{2} F_{2} \sin \theta_{2} \nonumber \]