8.5: Derivaciones

- Page ID

- 103638

Hemos dicho cómo es un secuente inicial, y hemos dado las reglas de inferencia. Derivaciones en el cálculo secuente se generan inductivamente a partir de estos: cada derivación es un secuente inicial por sí mismo, o consiste en una o dos derivaciones seguidas de una inferencia.

Definición\(\PageIndex{1}\): \(\Log{LK}\) derivation

Una\(\Log{LK}\) derivación de un secuente\(S\) es un árbol de secuentes que satisface las siguientes condiciones:

- Los secuentes superiores del árbol son los secuentes iniciales.

- El secuente más bajo del árbol es\(S\).

- Cada secuencia en el árbol excepto\(S\) es una premisa de una correcta aplicación de una regla de inferencia cuya conclusión se encuentra directamente debajo de esa secuencia en el árbol.

Entonces decimos que\(S\) es el secuente final de la derivación y que\(S\) es derivable en\(\Log{LK}\) (o\(\Log{LK}\) -derivable).

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{1}\)

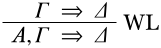

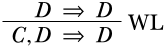

Cada secuencia inicial, p. ej.,\(C \Sequent C\) es una derivación. Podemos obtener una nueva derivación de esto aplicando, digamos, la\(\LeftR{\Weakening}\) regla,

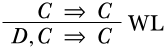

La regla, sin embargo, pretende ser general: podemos sustituir el\(A\) en la regla por cualquier frase, por ejemplo, también con\(D\). Si la premisa coincide con nuestro secuente inicial\(C \Sequent C\), eso significa que ambos\(\Gamma\) y\(\Delta\) son justos\(C\), y la conclusión sería entonces\(D, C \Sequent C\). Entonces, lo siguiente es una derivación:

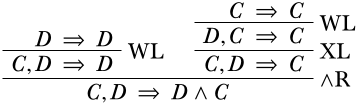

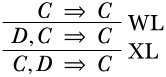

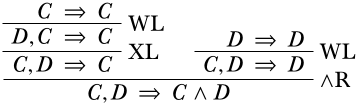

Ahora podemos aplicar otra regla, digamos\(\LeftR{\Exchange}\), que nos permite cambiar dos oraciones a la izquierda. Entonces, lo siguiente también es una derivación correcta:

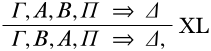

En esta aplicación de la norma, la cual se dio como

ambos\(\Gamma\) y\(\Pi\) estaban vacíos,\(\Delta\) es\(C\), y los papeles de\(A\) y\(B\) son interpretados por\(D\) y\(C\), respectivamente. De la misma manera, también vemos que

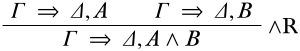

es una derivación. Ahora podemos tomar estas dos derivaciones, y combinarlas usando\(\RightR{\land}\). Esa regla era

En nuestro caso, los locales deben coincidir con los últimos secuentes de las derivaciones que terminan en las premisas. Eso quiere decir que\(\Gamma\) es\(C, D\),\(\Delta\) está vacío,\(A\) es\(C\) y\(B\) es\(D\). Entonces la conclusión, si la inferencia debe ser correcta, es\(C, D \Sequent C \land D\).

Por supuesto, también podemos revertir las premisas, entonces\(A\) sería\(D\) y\(B\) sería\(C\).