7.1: A - Números Complejos

- Page ID

- 113055

En este Apéndice damos una breve revisión de las propiedades aritméticas y básicas de los números complejos.

Como motivación, observe que la matriz de rotación

\[ A =\left(\begin{array}{cc}0&-1\\1&0\end{array}\right) \nonumber \]

tiene polinomio característico\(f(\lambda) = \lambda^2 + 1\). Un cero de esta función es una raíz cuadrada de\(-1\). Si queremos que este polinomio tenga una raíz, entonces tenemos que usar un sistema de números más grande: necesitamos declarar por fiat que existe una raíz cuadrada de\(-1\).

- El número imaginario\(i\) se define para satisfacer la ecuación\(i^2 = -1\).

- Un número complejo es un número de la forma\(a+bi\text{,}\) donde\(a,b\) están los números reales.

Se denota el conjunto de todos los números complejos\(\mathbb{C}\).

Los números reales son solo los números complejos de la forma\(a + 0i\text{,}\) por lo que\(\mathbb{R}\) está contenida en\(\mathbb{C}\).

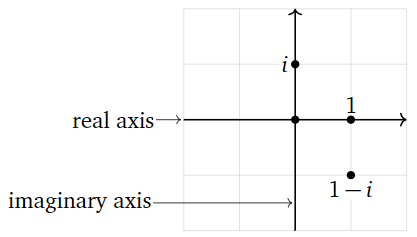

Podemos identificarnos\(\mathbb{C}\) con\(\mathbb{R}^2 \) por\(a+bi \longleftrightarrow {a\choose b}\). Entonces cuando dibujamos una imagen de\(\mathbb{C}\text{,}\) dibujamos el plano:

Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Podemos realizar todas las operaciones aritméticas habituales en números complejos: sumar, restar, multiplicar, dividir, valor absoluto. También hay una nueva operación importante llamada conjugación compleja.

- La adición se realiza por componentes:

\[ (a + bi) + (c + di) = (a + c) + (b + d)i. \nonumber \]

- La multiplicación se realiza usando distributividad y\(i^2=-1\text{:}\)

\[ (a+bi)(c+di) = ac + adi + bci + bdi^2 = (ac-bd) + (ad+bc)i. \nonumber \]

- La conjugación compleja reemplaza\(i\) con\(-i\text{,}\) y se denota con una barra:

\[ \overline{a+bi} = a - bi. \nonumber \]El número\(\overline{a+bi}\) se llama el conjugado complejo de\(a+bi\). Uno comprueba que para cualquiera de dos números complejos\(z,w\text{,}\) tenemos

\[ \overline{z+w} = \overline{ z} + \overline{ w} \quad\text{and}\quad \overline{zw} = \overline{z}\cdot\overline{w}. \nonumber \]Además, también\((a+bi)(a-bi) = a^2 + b^2\text{,}\) lo\(z\bar z\) es un número real no negativo para cualquier número complejo\(z\).

- El valor absoluto de un número complejo\(z\) es el número real\(|z| = \sqrt{z\overline{ z}}\text{:}\)

\[ |a+bi| = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}. \nonumber \]Uno comprueba que\(|zw| = |z|\cdot|w|.\)

- La división por un número real distinto de cero procede por componentes:

\[ \frac{a+bi}c = \frac ac + \frac bci. \nonumber \]

- La división por un número complejo distinto de cero requiere multiplicar el numerador y el denominador por el conjugado complejo del denominador:

\[ \frac zw = \frac{z\overline{ w}}{w\overline{ w}} = \frac{z\overline{ w}}{|w|^2}. \nonumber \]Por ejemplo,

\[ \frac{1+i}{1-i} = \frac{(1+i)^2}{1^2+(-1)^2} = \frac{1+2i+i^2}2 = i. \nonumber \]

- Las partes reales e imaginarias de un número complejo son

\[ \Re(a+bi) = a \qquad \Im(a+bi) = b. \nonumber \]

El objetivo de introducir números complejos es encontrar raíces de polinomios. Resulta que introducir\(i\) es suficiente para encontrar las raíces de cualquier polinomio.

Cada polinomio de grado\(n\) tiene raíces exactamente\(n\) (reales y) complejas, contadas con multiplicidad.

Equivalentemente, si\(f(x) = x^n + a_{n-1}x^{n-1} + \cdots + a_1x + a_0\) es un polinomio de grado\(n\text{,}\) entonces\(f\) factores como

\[ f(x) = (x-\lambda_1)(x-\lambda_2)\cdots(x-\lambda_n) \nonumber \]

para números complejos (no necesariamente distintos)\(\lambda_1,\lambda_2,\ldots,\lambda_n\).

La fórmula cuadrática da las raíces de un polinomio de grado 2, real o complejo:

\[ f(x) = x^2 + bx + c \implies x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4c}}2. \nonumber \]

Por ejemplo, si\(f(x) = x^2 - \sqrt 2x + 1\text{,}\) entonces

\[ x = \frac{\sqrt 2\pm\sqrt{-2}}2 = \frac{\sqrt 2}2(1\pm i) = \frac{1\pm i}{\sqrt 2}. \nonumber \]

Tenga en cuenta que si\(b,c\) son números reales, entonces las dos raíces son conjugados complejos.

Un número complejo\(z\) es real si y solo si\(z = \bar z\). Esto lleva a la siguiente observación.

Si\(f\) es un polinomio con coeficientes reales, y si\(\lambda\) es una raíz compleja de\(f\text{,}\) entonces así es\(\overline{\lambda}\text{:}\)

\[\begin{aligned}0=\overline{f(\lambda )}&=\overline{\lambda^n+a_{n-1}\lambda^{n-1}+\cdots +a_1\lambda +a_0} \\ &=\overline{\lambda}^n+a_{n-1}\overline{\lambda}^{n-1}+\cdots +a_1\overline{\lambda}+a_0=f(\overline{\lambda}).\end{aligned}\]

Por lo tanto, las raíces complejas de polinomios reales vienen en pares conjugados.

Un polinomio cúbico real tiene tres raíces reales, o una raíz real y un par conjugado de raíces complejas.

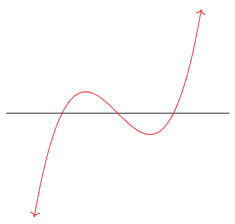

Por ejemplo,\(f(x) = x^3-x = x(x-1)(x+1)\) tiene tres raíces reales; su gráfica se ve así:

Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\)

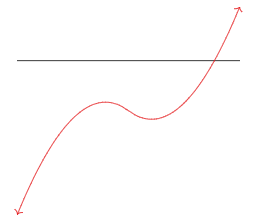

Por otro lado, el polinomio

\[ g(x) = x^3-5x^2+x-5 = (x-5)(x^2+1) = (x-5)(x+i)(x-i) \nonumber \]

tiene una raíz real\(5\) y un par conjugado de raíces complejas\(\pm i\). Su gráfica se ve así:

Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\)