5.7: La variación total (longitud) de una función f - E1 → E

- Page ID

- 114034

This page is a draft and is under active development.

La pregunta que consideraremos ahora es cómo definir razonablemente (y precisamente) la noción de la longitud de una curva (Capítulo 4, §10) descrita por una función\(f : E^{1} \rightarrow E\) sobre un intervalo\(I=[a, b],\) i.e\(f[I]\).,.

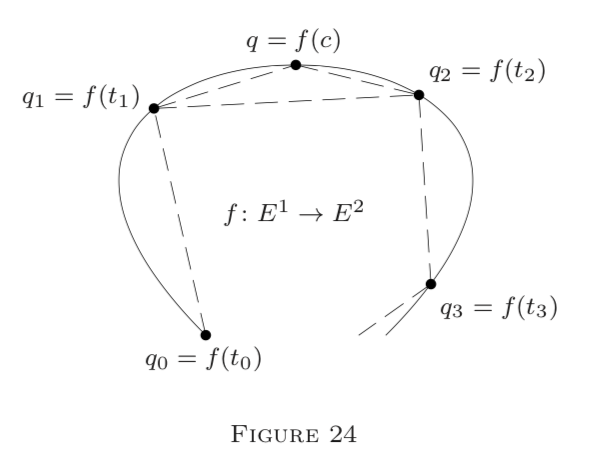

Se procede de la siguiente manera (ver Figura 24).

Subdividir\([a, b]\) por un conjunto finito de puntos\(P=\left\{t_{0}, t_{1}, \ldots, t_{m}\right\},\) con

\[a=t_{0} \leq t_{1} \leq \cdots \leq t_{m}=b;\]

\(P\)se llama una partición de\([a, b].\) Let

\[q_{i}=f\left(t_{i}\right), \quad i=1,2, \ldots, m,\]

y, para\(i=1,2, \ldots, m\),

\[\begin{aligned} \Delta_{i} f &=q_{i}-q_{i-1} \\ &=f\left(t_{i}\right)-f\left(t_{i-1}\right). \end{aligned}\]

También definimos

\[S(f, P)=\sum_{i=1}^{m}\left|\Delta_{i} f\right|=\sum_{i=1}^{m}\left|q_{i}-q_{i-1}\right|.\]

Geométricamente,\(\left|\Delta_{i} f\right|=\left|q_{i}-q_{i-1}\right|\) es la longitud del segmento de línea\(L\left[q_{i-1}, q_{i}\right]\) en\(E,\) y\(S(f, P)\) es la suma de tales longitudes, es decir, la longitud del polígono

\[W=\bigcup_{i=1}^{m} L\left[q_{i-1}, q_{i}\right]\]

inscrito en\(f[I];\) lo denotamos por

\[\ell W=S(f, P).\]

Ahora supongamos que agregamos un nuevo punto de partición\(c,\) con

\[t_{i-1} \leq c \leq t_{i}.\]

Luego obtenemos una nueva partición

\[P_{c}=\left\{t_{0}, \ldots, t_{i-1}, c, t_{i}, \ldots, t_{m}\right\},\]

llamado un refinamiento de\(P,\) y un nuevo polígono inscrito\(W_{c}\) en el que\(L\left[q_{i-1}, q_{i}\right]\) se sustituye por dos segmentos,\(L\left[q_{i-1}, q\right]\) y\(L\left[q, q_{i}\right],\) donde\(q=f(c);\) ver Figura 24. En consecuencia, el término\(\left|\Delta_{i} f\right|=\left|q_{i}-q_{i-1}\right|\) in\(S(f, P)\) se sustituye por

\[\left|q_{i}-q\right|+\left|q-q_{i-1}\right| \geq\left|q_{i}-q_{i-1}\right| \quad \text { (triangle law)}.\]

De ello se deduce que

\[S(f, P) \leq S\left(f, P_{c}\right) ; \text { i.e., } \ell W \leq \ell W_{c}.\]

De ahí que obtengamos el siguiente resultado.

La suma\(S(f, P)=\ell W\) no puede disminuir cuando\(P\) se refina.

Así, cuando se agregan nuevos puntos de partición,\(S(f, P)\) crece en general; es decir, se acerca a algún valor supremo (finito o no). En términos generales, el polígono inscrito\(W\) se “acerca” a la curva. Es natural definir la longitud deseada de la curva para que sea la\(l u b\) de todas las longitudes,\(\ell W,\) es decir, de todas las sumas\(S(f, P)\) resultantes de las diversas particiones\(P\). A este supremo también se le llama la variación total de\(f\)\([a, b],\) sobredenotado\(V_{f}[a, b].\)

Dada cualquier función\(f : E^{1} \rightarrow E,\) y\(I=[a, b] \subset E^{1},\) establecemos

\[V_{f}[I]=V_{f}[a, b]=\sup _{P} S(f, P)=\sup _{P} \sum_{i=1}^{m}\left|f\left(t_{i}\right)-f\left(t_{i-1}\right)\right| \geq 0 \text { in } E^{*},\]

donde el supremo está sobre todas las particiones\(P=\left\{t_{0}, \ldots, t_{m}\right\}\) de\(I.\) Llamamos a\(V_{f}[I]\) la variación total, o longitud, de\(f\) en\(I.\) Brevemente, lo denotamos por\(V_{f}\).

Nota 1. Si\(f\) es continuo en\([a, b],\) el conjunto de imágenes\(A=f[I]\) es un arco (Capítulo 4, §10). Se acostumbra llamar a\(V_{f}[I]\) la longitud de ese arco, denotado\(\ell_{f} A\) o brevemente\(\ell A.\) Note, sin embargo, que bien puede haber otra función\(g,\) continua en un intervalo\(J,\) tal que\(g[J]=A\) pero\(V_{f}[I] \neq V_{g}[J],\) y\(\ell_{f} A \neq \ell_{g} A.\) así es más seguro decir “la longitud de \(A\)como se describe\(f\) en el I.” Sólo para arcos simples (donde\(f\) está uno a uno), es "\(\ell A\)" inequívoco. (Ver Problemas 6-8.)

En las proposiciones siguientes,\(f\) es una función arbitraria,\(f : E^{1} \rightarrow E\).

Si\(a \leq c \leq b,\) entonces

\[V_{f}[a, b]=V_{f}[a, c]+V_{f}[c, b];\]

es decir, la longitud del todo es igual a la suma de las longitudes de las partes.

- Prueba

-

Tome cualquier partición\(P=\left\{t_{0}, \ldots, t_{m}\right\}\) de\([a, b].\) Si\(c \notin P,\) refina\(P\) a

\[P_{c}=\left\{t_{0}, \ldots, t_{i}, c, t_{i}, \ldots, t_{m}\right\}.\]

Entonces por Corolario 1,\(S(f, P) \leq S\left(f, P_{c}\right)\).

Ahora\(P_{c}\) se divide en particiones de\([a, c]\) y\([c, b],\) es decir,

\[P^{\prime}=\left\{t_{0}, \ldots, t_{i-1}, c\right\} \text { and } P^{\prime \prime}=\left\{c, t_{i}, \ldots, t_{m}\right\},\]

para que

\[S\left(f, P^{\prime}\right)+S\left(f, P^{\prime \prime}\right)=S\left(f, P_{c}\right) . \text { (Verify!)}\]

Por lo tanto\(\left(\text {as } V_{f} \text { is the } l u b \text { of the corresponding sums}\right)\),

\[V_{f}[a, c]+V_{f}[c, d] \geq S\left(f, P_{c}\right) \geq S(f, P).\]

Como\(P\) es una partición arbitraria de también\([a, b],\) tenemos

\[V_{f}[a, c]+V_{f}[c, b] \geq \sup S(f, P)=V_{f}[a, b].\]

Por lo tanto, queda por demostrar que, a la inversa,

\[V_{f}[a, b] \geq V_{f}[a, c]+V_{f}[c, b].\]

Este último es trivial si\(V_{f}[a, b]=+\infty.\) Así asume\(V_{f}[a, b]=K<+\infty.\) Let\(P^{\prime}\) y\(P^{\prime \prime}\) ser cualquier partición de\([a, c]\) y\([c, b],\) respectivamente. Entonces\(P^{*}=P^{\prime} \cup P^{\prime \prime}\) es una partición de\([a, b],\) y

\[S\left(f, P^{\prime}\right)+S\left(f, P^{\prime \prime}\right)=S\left(f, P^{*}\right) \leq V_{f}[a, b]=K,\]

de donde

\[S\left(f, P^{\prime}\right) \leq K-S\left(f, P^{\prime \prime}\right).\]

Manteniendo\(P^{\prime \prime}\) fijo y variando\(P^{\prime},\) vemos que\(K-S\left(f, P^{\prime \prime}\right)\) es un límite superior de todas\(S\left(f, P^{\prime}\right)\) partes\([a, c].\) Por lo tanto

\[V_{f}[a, c] \leq K-S\left(f, P^{\prime \prime}\right)\]

o

\[S\left(f, P^{\prime \prime}\right) \leq K-V_{f}[a, c].\]

Del mismo modo, variando ahora\(P^{\prime \prime},\) obtenemos

\[V_{f}[c, b] \leq K-V_{f}[a, c]\]

o

\[V_{f}[a, c]+V_{f}[c, b] \leq K=V_{f}[a, b],\]

según sea necesario. Así todo está probado. \(\quad \square\)

Si\(a \leq c \leq d \leq b,\) entonces

\[V_{f}[c, d] \leq V_{f}[a, b].\]

- Prueba

-

Por Teorema 1,

\[V_{f}[a, b]=V_{f}[a, c]+V_{f}[c, d]+V_{f}[d, b] \geq V_{f}[c, d] . \quad \square\]

Si\(V_{f}[a, b]<+\infty,\) decimos que\(f\) es de variación acotada sobre\(I=[a, b],\) y que el conjunto\(f[I]\) es rectificable (por\(f\) on\(I)\).

Para cada uno\(t \in[a, b]\),

\[|f(t)-f(a)| \leq V_{f}[a, b].\]

De ahí\(f\) que si es de variación acotada sobre\([a, b],\) ella está acotada en\([a, b]\).

- Prueba

-

Si\(P=\{a, t, b\},\) así lo\(t \in[a, b],\) deja

\[|f(t)-f(a)| \leq|f(t)-f(a)|+|f(b)-f(t)|=S(f, P) \leq V_{f}[a, b],\]

demostrando nuestra primera afirmación. De ahí

\[(\forall t \in[a, b]) \quad|f(t)| \leq|f(t)-f(a)|+|f(a)| \leq V_{f}[a, b]+|f(a)|.\]

Esto prueba la segunda aseveración. \(\quad \square\)

Nota 2. Ni la brevedad, ni la continuidad, ni la diferenciabilidad de\(f\) on\([a, b]\) implica\(V_{f}[a, b]<+\infty,\) sino la limitacion de\(f^{\prime}\) hace. (Ver Problemas 1 y 3.)

Una función\(f\) es finita y constante en\([a, b]\) iff\(V_{f}[a, b]=0\).

La prueba se deja en manos del lector. (Utilice el Corolario 3 y las definiciones.

Dejar\(f, g, h\) ser real o complejo (o dejar\(f\) y\(g\) ser vector valorado y\(h\) escalar). Entonces en cualquier intervalo\(I=[a, b],\) tenemos

i)\(V_{|f|} \leq V_{f}\);

ii)\(V_{f \pm g} \leq V_{f}+V_{g} ;\) y

(iii)\(V_{h f} \leq s V_{f}+r V_{h},\) con\(r=\sup _{t \in I}|f(t)|\) y\(s=\sup _{t \in I}|h(t)|\).

De ahí que si\(f, g,\) y\(h\) son de variación acotada sobre\(I,\) así son\(f \pm g, h f,\) y\(|f|\).

- Prueba

-

Primero probamos (iii).

Toma cualquier partición\(P=\left\{t_{0}, \ldots, t_{m}\right\}\) de\(I.\) Then

\ [\ comenzar {alineado}\ izquierda|\ Delta_ {i} h f\ derecha| &=\ izquierda|h\ izquierda (t_ {i}\ derecha) f\ izquierda (t_ {i}\ derecha) -h\ izquierda (t_ {i-1}\ derecha) f\ izquierda (t_ {i-1}\ derecha)\ derecha|\\ &\ izquierda\ izquierda|h\ izquierda (t_ {i}\ derecha) f\ izquierda (t_ {i}\ derecha) -h\ izquierda (t_ {i-1}\ derecha) f\ izquierda (t_ {i}\ derecha)\ derecha|+\ izquierda|h\ izquierda (t_ {i-1}\ derecha) f\ izquierda (t_ {i}\ derecha) -h\ izquierda (t_ {i-1}\ derecha) -h\ izquierda (t_ {i-1}\ derecha) -h\ izquierda (t_ { i-1}\ derecha) f\ izquierda (t_ {i-1}\ derecha)\ derecha|\\ &

=\ izquierda|f\ izquierda (t_ {i}\ derecha)\ izquierda\ |\ Delta_ {i} h|+| h\ izquierda (t_ {i-1}\ derecha)\ derecha\ |\ Delta_ {i} f\ derecha|

\\ &\ leq r\ ft|\ Delta_ {i} h\ derecha|+s\ izquierda|\ Delta_ {i} f\ derecha|. \ end {alineado}\]Sumando estas desigualdades, obtenemos

\[S(h f, P) \leq r \cdot S(h, P)+s \cdot S(f, P) \leq r V_{h}+s V_{f}.\]

Como esto tiene para todas las sumas\(S(h f, P),\) que tiene para su supremo, entonces

\[V_{h f}=\sup S(h f, P) \leq r V_{h}+s V_{f},\]

según lo reclamado.

Del mismo modo, i) se desprende de

\[| | f\left(t_{i}\right)|-| f\left(t_{i-1}\right)| | \leq\left|f\left(t_{i}\right)-f\left(t_{i-1}\right)\right|.\]

La prueba análoga de (ii) se deja al lector.

Por último, (i) a (iii) implican que\(V_{f}, V_{f \pm g}\), y\(V_{h f}\) son finitos si\(V_{f}, V_{g},\) y\(V_{h}\) son. Esto prueba nuestra última aseveración. \(\quad \square\)

Nota 3. También\(f / h\) es de variación limitada sobre\(I\) si\(f\) y\(h\) son, siempre que\(h\) esté delimitado lejos de 0 en\(I ;\) i.e.

\[(\exists \varepsilon>0) \quad|h| \geq \varepsilon \text { on } I.\]

(Ver Problema 5.)

Teoremas especiales se aplican en caso de que el espacio de rango\(E\) sea\(E^{1}\) o\(E^{n}\left(^{*} \text { or } C^{n}\right)\).

(i) Una función real\(f\) es de variación limitada en\(I=[a, b]\) iff\(f=g-h\) para algunas funciones reales no decrecientes\(g\) y\(h\) en\(I.\)

(ii) Si\(f\) es real y monótona en\(I,\) ella es de variación acotada ahí.

- Prueba

-

Demostramos (ii) primero.

\(f \uparrow\)Vamos\(I.\) Si\(P=\left\{t_{0}, \ldots, t_{m}\right\},\) entonces

\[t_{i} \geq t_{i-1} \text { implies } f\left(t_{i}\right) \geq f\left(t_{i-1}\right).\]

Por lo\(\left|\Delta_{i} f\right|=\Delta_{i} f.\) tanto,\(\Delta_{i} f \geq 0;\) es decir,

\[\begin{aligned} S(f, P) &=\sum_{i=1}^{m}\left|\Delta_{i} f\right|=\sum_{i=1}^{m} \Delta_{i} f=\sum_{i=1}^{m}\left[f\left(t_{i}\right)-f\left(t_{i-1}\right)\right] \\ &=f\left(t_{m}\right)-f\left(t_{0}\right)=f(b)-f(a) \end{aligned}\]

para cualquier\(P.\) (¡Verifica!) Esto implica que también

\[V_{f}[I]=\sup S(f, P)=f(b)-f(a)<+\infty.\]

Así se demuestra (ii).

Ahora para (i), vamos\(f=g-h\) con\(g \uparrow\) y\(h \uparrow\) sigue\(I\). Por (ii),\(g\) y\(h\) son de variación acotada en\(I.\) Por lo tanto lo es\(f=g-h\) por el Teorema 2 (última cláusula).

Por el contrario, supongamos\(V_{f}[I]<+\infty.\) Luego definir

\[g(x)=V_{f}[a, x], x \in I, \text { and } h=g-f \text { on } I,\]

así\(f=g-h,\) y sólo queda por demostrar eso\(g \uparrow\) y\(h \uparrow\).

Para probarlo, vamos\(a \leq x \leq y \leq b.\) Entonces Teorema 1 rinde

\[V_{f}[a, y]-V_{f}[a, x]=V_{f}[x, y];\]

es decir,

\[g(y)-g(x)=V_{f}[x, y] \geq|f(y)-f(x)| \geq 0 \quad \text { (by Corollary 3).}\]

De ahí\(g(y) \geq g(x).\) también, como\(h=g-f,\) tenemos

\[\begin{aligned} h(y)-h(x) &=g(y)-f(y)-[g(x)-f(x)] \\ &=g(y)-g(x)-[f(y)-f(x)] \\ & \geq 0 \quad \text {by (2).} \end{aligned}\]

Así\(h(y) \geq h(x).\) vemos que eso\(a \leq x \leq y \leq b\) implica\(g(x) \leq g(y)\) y\(h(x) \leq h(y),\) así\(h \uparrow\) y\(g \uparrow,\) efectivamente. \(\quad \square\)

(i) Una función\(f : E^{1} \rightarrow E^{n}\left(^{*} C^{n}\right)\) es de variación limitada en\(I=[a, b]\) iff todos sus componentes\(\left(f_{1}, f_{2}, \ldots, f_{n}\right)\) son.

(ii) Si este es el caso, entonces límites finitos\(f\left(p^{+}\right)\) y\(f\left(q^{-}\right)\) existen para cada\(p \in[a, b) \text { and } q \in(a, b].\)

- Prueba

-

(i) Tomar cualquier partición\(P=\left\{t_{0}, \ldots, t_{m}\right\}\) de\(I.\) Entonces

\[\left|f_{k}\left(t_{i}\right)-f_{k}\left(t_{i-1}\right)\right|^{2} \leq \sum_{j=1}^{n}\left|f_{j}\left(t_{i}\right)-f_{j}\left(t_{i-1}\right)\right|^{2}=\left|f\left(t_{i}\right)-f\left(t_{i-1}\right)\right|^{2};\]

es decir,\(\left|\Delta_{i} f_{k}\right| \leq\left|\Delta_{i} f\right|, i=1,2, \ldots,\text{ } m.\) Así

\[(\forall P) \quad S\left(f_{k}, P\right) \leq S(f, P) \leq V_{f},\]

y\(V_{f_{k}} \leq V_{f}\) sigue. Por lo tanto

\[V_{f}<+\infty \text { implies } V_{f_{k}}<+\infty, \quad k=1,2, \ldots,\text{ } n.\]

Lo contrario sigue por Teorema 2 ya que\(f=\sum_{k=1}^{n} f_{k} \vec{e}_{k}.\) (¡Explique!)

(ii) Para funciones monótonas reales,\(f\left(p^{+}\right)\) y\(f\left(q^{-}\right)\) existir por el Teorema 1 del Capítulo 4, §5. Esto también se aplica si\(f\) es real y de variación acotada, pues por Teorema 3,

\[f=g-h \text { with } g \uparrow \text { and } h \uparrow \text { on } I,\]

y así

\[f\left(p^{+}\right)=g\left(p^{+}\right)-h\left(p^{+}\right) \text { and } f\left(q^{-}\right)=g\left(q^{-}\right)-h\left(q^{-}\right) \text { exist.}\]

Los límites son finitos ya que\(f\) está delimitado\(I\) por el Corolario 3.

Vía componentes (Teorema 2 del Capítulo 4, §3), esto también se aplica a las funciones\(f : E^{1} \rightarrow E^{n}.\) (¿Por qué?) En particular, (ii) se aplica a funciones complejas (tratar\(C\) como\(E^{2}\) (*y así también se extiende a funciones\(f : E^{1} \rightarrow C^{n}.\)). \(\quad \square\)

También hemos demostrado el siguiente corolario.

Una función compleja\(f : E^{1} \rightarrow C\) es de variación limitada sobre\([a, b]\) si sus partes reales e imaginarias son. (Véase Capítulo 4, §3, Nota 5).