12.3: Tamaños Relativos de Conjuntos

- Page ID

- 118313

Hemos definido un conjunto\(A\) para que sea finito cuando podamos contar sus elementos emparejándolos bijectivamente con los elementos de algún conjunto de conteo\(\mathbb{N}_{<m}\text{.}\) Y en este caso, definiendo\(\vert A \vert = m\text{,}\) estamos declarando que\(A\) tiene el mismo “tamaño” que\(\mathbb{N}_{<m}\text{.}\)

Ampliando esta idea, podemos pensar en cada bijección como usar los elementos de un conjunto para “contar” los elementos de otro.

conjuntos\(A\) y\(B\) para los que existe una bijección\(A \to B\)

Si\(B\) tiene el mismo tamaño que\(A\text{,}\) entonces\(A\) tiene el mismo tamaño que\(B\text{.}\)

- Comprobante.

-

Si\(f: A \rightarrow B\) es una biyección, entonces también lo es\(f^{-1} : B \rightarrow A\text{.}\)

Si\(A\) tiene el mismo tamaño que\(B\) y\(B\) tiene el mismo tamaño que\(C\text{,}\) entonces\(A\) tiene el mismo tamaño que\(C\text{.}\)

- Comprobante.

-

Esto le queda a usted como Ejercicio 12.6.5.

Esperamos que nuestra noción general del mismo tamaño coincida con solo contar elementos de conjuntos finitos y obtener el mismo resultado.

Asumir\(A\) y\(B\) son conjuntos finitos. Entonces\(\vert A \vert = \vert B \vert\) si y solo si\(A\) y\(B\) tienen el mismo tamaño.

- Comprobante.

-

Asumir igual cardinalidad, mostrar el mismo tamaño.

Asumir\(\vert A \vert = \vert B \vert = m\text{.}\) Entonces por definición existen bijecciones\(f: \mathbb{N}_{<m} \rightarrow A\) y\(g: \mathbb{N}_{<m} \rightarrow B\text{.}\) Ahora\(g \circ f^{-1}\) es una bijección\(A \to B\text{,}\) así\(A\) y\(B\) tienen el mismo tamaño según la definición técnica.

Asumir el mismo tamaño, mostrar igual cardinalidad.

Asumir\(A\) y\(B\) tener el mismo tamaño. Entonces por definición existe una bijección\(f: A \rightarrow B\text{.}\) Ahora, también hemos asumido que\(A\) es finito, entonces existe una bijección\(g: \mathbb{N}_{<m} \rightarrow A\text{,}\) donde\(m = \vert A \vert\text{.}\) Entonces\(f \circ g: \mathbb{N}_{<m} \rightarrow B\) es una bijección que demuestra\(\vert B \vert = m\) también.

Tu intuición puede fallarte al considerar “tamaños” de conjuntos infinitos. En particular, es posible tener\(\vert A \vert = \vert B \vert = \infty\text{,}\) dónde\(A\) y\(B\) no tener el mismo tamaño.

A pesar de\(\mathbb{Z}\) que\(\mathbb{N} \subsetneqq \mathbb{Z}\text{,}\)\(\mathbb{N}\) y tienen el mismo tamaño! A continuación se define una biyección\(f: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}\text{.}\)

| \(n\) | \(0\) | \(1\) | \(2\) | \(3\) | \(4\) | \(\cdots\) |

| \(f(n)\) | \(0\) | \(-1\) | \(1\) | \(-2\) | \(2\) | \(\cdots\) |

Esta biyección se puede expresar por la fórmula

En el Capítulo 13, vamos a ver que a pesar de que\(\vert \mathbb{N} \vert = \vert \mathbb{R} \vert = \infty\text{,}\) los conjuntos\(\mathbb{N}\) y\(\mathbb{R}\) no tienen el mismo tamaño!

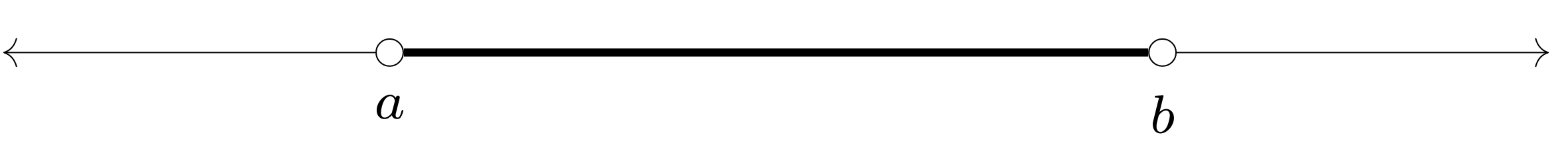

Recordemos del cálculo de primer año que para\(a,b \in \mathbb{R}\) con\(a \lt b\text{,}\) definimos el intervalo abierto de\(a\)\(b\) a ser el conjunto de todos los números reales estrictamente entre\(a\) y\(b\text{:}\)

\ begin {ecuación*} (a, b) =\ {x\ in\ mathbb {R}\ vert a\ lt x\ lt b\}\ texto {.} \ end {ecuación*}

Resulta que, aunque puedan tener diferentes longitudes, ¡el intervalo\((a,b)\) y el intervalo unitario\((0,1)\) tienen el mismo tamaño! (Es decir, de alguna manera contienen el mismo “número” de números.)

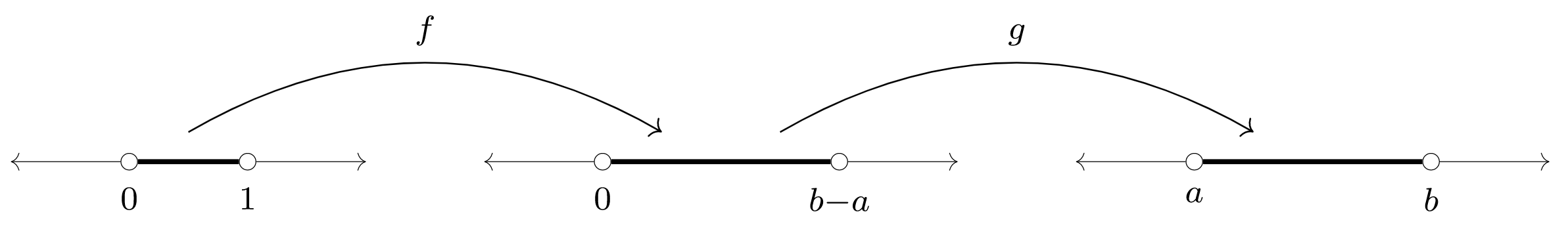

Construir una biyección\((0,1)\to(a,b)\) en dos pasos.

- El mapa

\ begin {alinear*} f\ colon (0,1) &\ to (0, b-a),\\ x &\ mapsto (b-a) x,\ end {align*}es una biyección. (¡Cheque!)

- El mapa

\ begin {alinear*} g\ colon (0, b-a) &\ to (a, b),\\ x &\ mapsto x+a,\ end {align*}es una biyección. (¡Cheque!)

Entonces\(g\circ f: (0,1) \rightarrow (a,b)\) es una biyección.

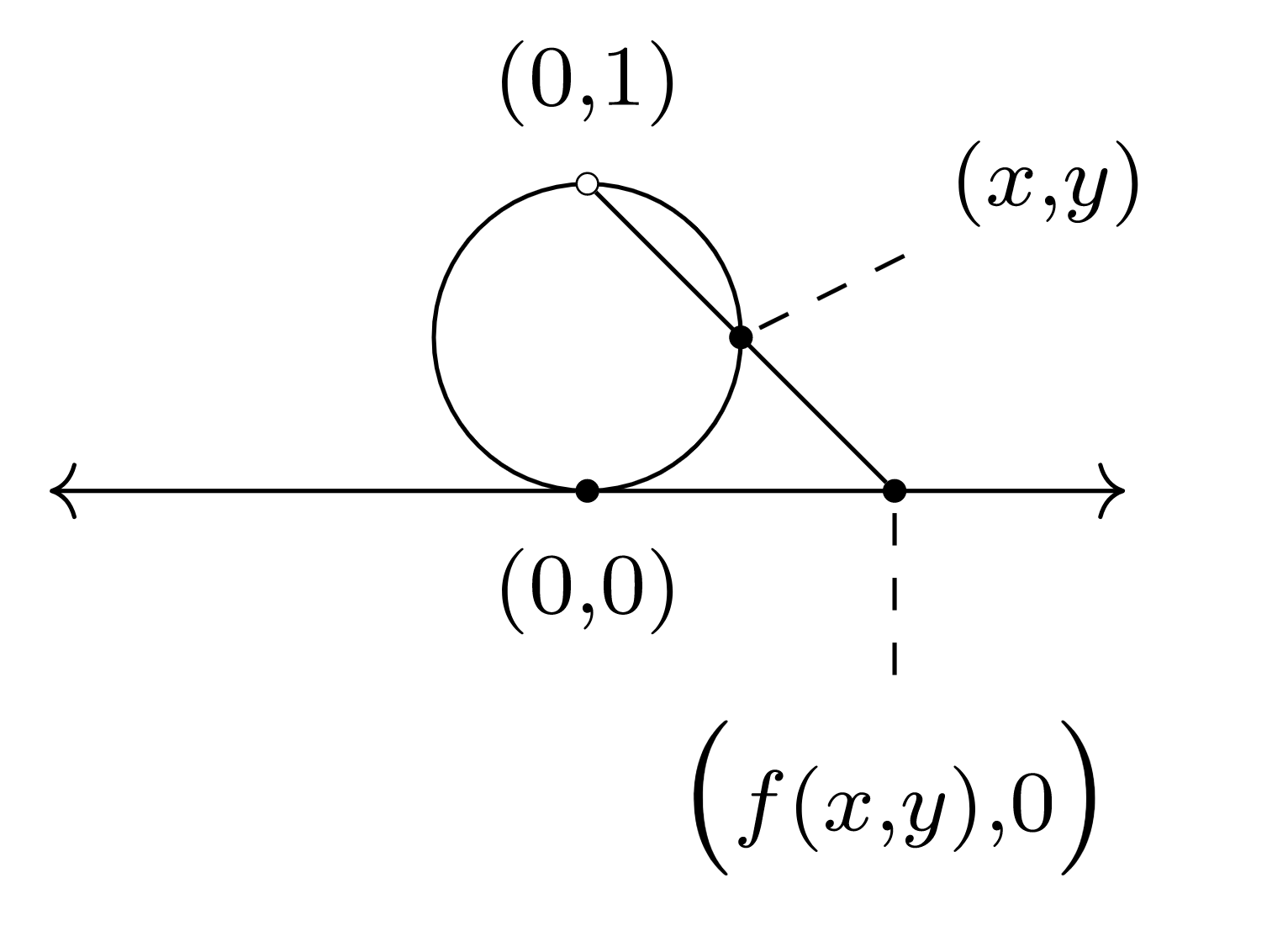

Definir

\ begin {alinear*} S & =\ {(x, y)\ in\ mathbb {R} ^2\ vert x^2 + (y-\ dfrac {1} {2}) ^2 =\ dfrac {1} {4}\}\ texto {,} &\ hat {S} & = S\ setmenos\ {(0,1)\}\ texto {.} \ end {align*}

Aquí,\(S\) hay un círculo en el plano con radio\(\dfrac{1}{2}\) y centro\((0,\dfrac{1}{2})\text{,}\) y\(\hat{S}\) es el círculo\(S\) “perforado” en el “polo norte”.

Afirmamos que\(\hat{S}\) tiene el mismo tamaño que\(\mathbb{R}\text{.}\) Construir una bijección\(\hat{S}\to\mathbb{R}\) en dos pasos.

- Dejar\(X\) representar el\(x\) eje -en el plano, i.e.

\ begin {ecuación*} X =\ {(x,0)\ vert x\ in\ mathbb {R}\}\ subseteq\ mathbb {R} ^2\ text {.} \ end {equation*}

Dejar\(f: \hat{S} \rightarrow X\) definirse de la siguiente manera: para\((x,y)\in \hat{S}\text{,}\) let\(f(x,y)\) ser la\(x\) -intercepción de la línea a través de puntos\((0,1),(x,y)\text{.}\)

Entonces\(f\) es una biyección. (¡Cheque!)

- También tenemos una bijección\(g: X \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) por\(g(x,0) = x\text{.}\)

Por lo tanto, la composición\(g\circ f : \hat{S} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) es una biyección.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{3}\) y Ejemplo se\(\PageIndex{4}\) pueden combinar para demostrar que cada intervalo\((a,b)\) de longitud finita de números reales tiene el mismo tamaño que el conjunto completo\(\mathbb{R}\) de números reales. Ver Ejercicio 12.6.6.