19.4: Total de Órdenes

- Page ID

- 118251

Definición: Elementos comparables

elementos\(a,b\) en un conjunto parcialmente ordenado de tal manera\(a \preceq b\) que\(b \preceq a\)

Definición: Elementos Incomparables

elementos que no son comparables

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{1}\): Comparable and incomparable subsets.

Let\(U\) representar algún conjunto universal que contiene al menos dos elementos, y considerar\(\mathscr{P}(U)\) parcialmente ordenado por\(\mathord{\subseteq}\text{.}\)

- Tanto el conjunto\(\emptyset\) vacío como el conjunto universal\(U\) son comparables a cada elemento de\(\mathscr{P}(U)\text{.}\)

- Porque\(x,y\in U\) con\(x\ne y\text{,}\) entonces\(\{x\},\{y\}\) son incomparables.

- De hecho, por cada subconjunto no vacío y apropiado\(A \subsetneqq U\) existe un subconjunto\(B \subseteq U\) que es incomparable de\(A\text{:}\) tomar\(B = A^C\text{.}\)

No obstante, no dejes que los dos segundos puntos anteriores te lleven por mal camino: no es necesario que los subconjuntos sean disjuntos para ser incomparables. Siempre y cuando cada uno de un par de subconjuntos contenga un elemento que el otro no, entonces los dos serán incomparables por\(\mathord{\subseteq}\text{.}\)

Definición: Total Order

un orden parcial en un conjunto tal que cada par de elementos es comparable

Definición: Conjunto totalmente ordenado

un conjunto equipado con un pedido total

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{2}\): Subset order is not total.

Para el\(U\text{,}\) pedido\(\mathord{\subseteq}\) de conjunto universal no\(\mathscr{P}(U)\) es total excepto cuando\(\vert U \vert \le 1\text{.}\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{3}\): Usual order of numbers is total.

Nuestro pedido habitual para números,\(\mathord{\leq}\text{,}\) es un pedido total\(\mathbb{N}\text{,}\)\(\mathbb{Z}\text{,}\) encendido\(\mathbb{Q}\text{,}\) o encendido\(\mathbb{R}\text{.}\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{4}\): Total order on alphabet induces total order on words.

Si\(\mathord{\preceq}\) es un orden total en un alfabeto\(\Sigma\text{,}\) entonces el orden lexicográfico\(\preceq^\ast\) descrito en el Ejemplo 19.2.6 es un orden total en el conjunto de palabras\(\Sigma^{\ast}\text{.}\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{5}\): Pulling back a total order through an injection.

Si\(B\) está totalmente ordenado y usamos una inyección\(f: A \hookrightarrow B\) para “tirar hacia atrás” el pedido en\(B\) un pedido encendido\(A\) (ver Ejemplo 19.2.10), entonces el pedido recién creado en también\(A\) será total.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{6}\): Countable can be totally ordered.

Si\(A\) es un conjunto contablemente infinito, entonces existe una biyección\(f: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow A\text{.}\) Podemos usar la inversa\(f^{-1}: A \rightarrow \mathbb{N}\) para “tirar hacia atrás” el orden total habitual\(\mathord{\le}\) en\(\mathbb{N}\) un orden total encendido\(A\) (ver Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{5}\)).

Otro punto de vista sobre esto es que nuestra bijección\(f\) crea una secuencia infinita

\ begin {ecuación*} a_0, a_1, a_2,\ ldots\ text {,}\ end {ecuación*}

donde cada elemento de\(A\) aparece exactamente una vez. Esta secuencia se puede convertir en una especificación del orden total activado\(A\) simplemente convirtiendo las comas en\(\mathord{\le}\) símbolos:

\ begin {ecuación*} a_0\ le a_1\ le a_2\ le\ cdots\ texto {.} \ end {ecuación*}

El patrón de Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{6}\) se vuelve aún más simple cuando lo aplicamos a un conjunto finito: un orden total en un conjunto finito no es diferente de un orden de los elementos del conjunto en una lista, como

\ begin {equation*} a_0, a_1, a_2,\ ldots, a_n\ end {ecuación*} simplemente se

puede convertir en

\ begin {ecuación*} a_0\ le a_1\ le a_2\ le\ cdots\ le a_n\ text {,}\ end {ecuación*}

y viceversa.

Si\(A\) es un conjunto finito, totalmente ordenado, ¿cómo se ve el diagrama de Hasse correspondiente?

La respuesta a esta pregunta está contenida en la observación\(\PageIndex{1}\).

Un orden parcial en un conjunto finito es total si y solo si su diagrama Hasse forma una sola línea vertical.

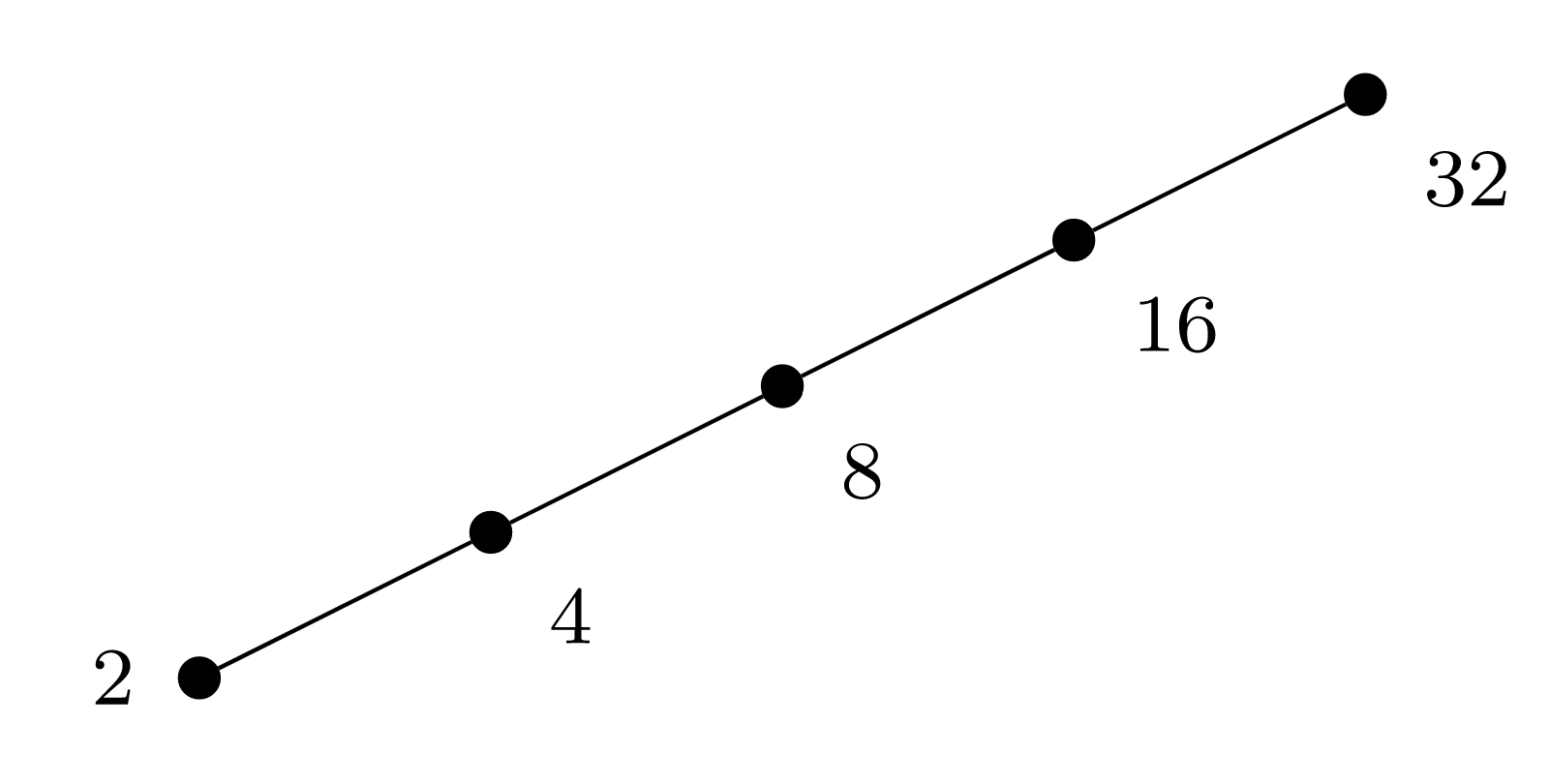

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{7}\): A totally ordered finite set.

La figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) exhibe el diagrama de Hasse para el orden total\(\mathord{\mid}\) en el set\(\{2,4,8,16,32\}\text{,}\) aunque hemos dibujado el diagrama en una inclinación desde la vertical para que sea más fácil ver todo el diagrama de un vistazo.