3.1: El Algoritmo Euclidiana

- Page ID

- 111475

Lema 3.1

En el algoritmo de división de Definition2.4, tenemos\(\gcd(r_{1},r_{2}) = \gcd(r_{2}, r_{3})\).

- Prueba

-

Por un lado, tenemos\(r_{1} = r_{2}q_{2}+r_{3}\), y así cualquier divisor común de\(r_{2}\) y también\(r_{3}\) debe ser un divisor de\(r_{1}\) (y de\(r_{2}\)). Viceversa\(r_{1}-r_{2}q_{2} = r_{3}\), ya que, tenemos ese cualquier divisor común de\(r_{1}\) y también\(r_{2}\) debe ser un divisor de\(r_{3}\) (y de\(r_{2}\)).

Así, al calcular\(r_{3}\), el residuo de\(r_{1}\) módulo\(r_{2}\), hemos simplificado el cómputo de\(\gcd (r_{1}, r_{2})\). Esto se debe a que\(r_{3}\) es estrictamente menor (en valor absoluto) que ambos\(r_{1}\) y\(r_{2}\). A su vez, el cálculo de\(\gcd (r_{2}, r_{3})\) puede simplificarse de manera similar, y así se puede repetir el proceso. Dado que la\(r_{i}\) forma una secuencia decreciente monótona en\(\mathbb{N}\), este proceso debe terminar cuando\(r_{n}+1 = 0\) después de un número finito de pasos. Entonces tenemos\(gcd(r_{1},r_{2}) = gcd(r_{n},0) = r_{n}\).

Corolario 3.2

Dado\(r_{1} > r_{2} > 0\), aplicar el algoritmo de división hasta\(r_{n} > r_{n+1} = 0\). Entonces\(\gcd (r_{1}, r_{2}) = \gcd(r_{n}, 0) = r_{n}\). Como\(r_{i}\) es decreciente, el algoritmo siempre termina.

Definición 3.3

La aplicación repetida del algoritmo de división para calcular\(\gcd(r_{1}, r_{2})\) se denomina algoritmo euclidiano.

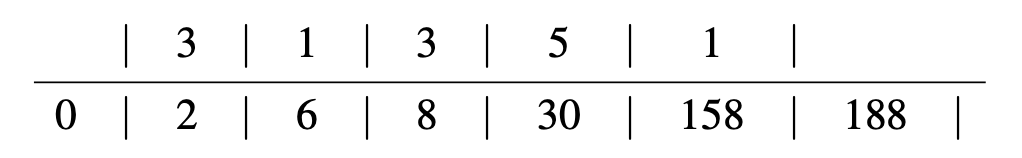

Ahora damos un marco para reducir el desorden de estos cálculos repetidos. Supongamos que queremos calcular\(\gcd(188, 158)\). Hacemos los siguientes cálculos:

\[188 = 158·1+30 \nonumber\]

\[158 = 30·5+8 \nonumber\]

\[30 = 8·3+6 \nonumber\]

\[8 = 6·1+2 \nonumber\]

\[6 = 2·3+0 \nonumber\]

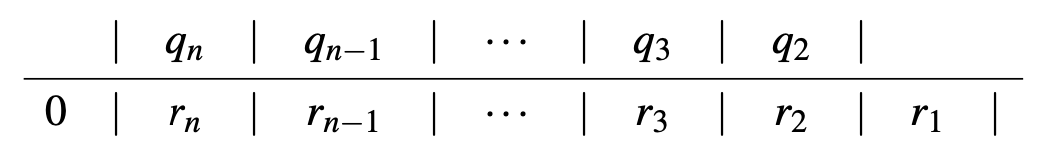

Eso lo vemos\(\gcd(188,158) = 2\). Los números que multiplican el\(r_{i}\) son los cocientes del algoritmo de división (ver la prueba de Lemma 2.3). Si los llamamos\(q_{i-1}\), el cómputo se ve de la siguiente manera:

\[\begin{array} {c} {r_{1} = r_{2} q_{2}+r_{3}}\\ {r_{2} = r_{3} q_{3}+r_{4}}\\ {\vdots}\\ {r_{n-3} = r_{n-2} q_{n-2}+r_{n-3}}\\ {r_{n-2} = r_{n-1} q_{n-1}+r_{n-2}}\\ {r_{n-1} = r_{n} q_{n}+0} \end{array}\]

donde usamos la convención que\(r_{n+1} = 0\) mientras\(r_{n} \ne 0\). Observe que con esa convención, (3.1) consiste en\(n-1\) pasos. Una forma mucho más concisa (en parte basada en una sugerencia de Katahdin [16]) para renderizar este cálculo es la siguiente.

Así, cada paso\(r_{i+1} |r_{i}|\) es similar a la división larga habitual, salvo que su cociente\(q_{i+1}\) se coloca arriba\(r_{i+1}\) (y no arriba\(r_{i}\)), mientras que su resto\(r_{i+2}\) se coloca todo el camino a la izquierda de\(r_{i+1}\). El ejemplo que elaboramos antes de ahora parece:

Hay una hermosa visualización de este proceso esbozado en el ejercicio 3.4.