1.10: Triángulos congruentes

- Page ID

- 114745

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Nuestro siguiente objetivo es darle un significado riguroso al (iv) de la Sección 1.1. Para ello, introducimos la noción de triángulos congruentes así que en lugar de “si giramos o desplazamos no veremos la diferencia” decimos que para los triángulos, se mantiene la congruencia de lado ángulo-lado; es decir, dos triángulos son congruentes si tienen dos pares de lados iguales y la misma medida de ángulo entre estos lados .

Un triple ordenado de puntos distintos en un espacio métrico\(\mathcal{X}\), digamos\(A, B, C\), se llama triángulo\(ABC\) (brevemente\(\triangle ABC\)). Tenga en cuenta que los triángulos\(ABC\) y\(ACB\) son considerados como diferentes.

Dos triángulos\(A'B'C'\) y\(ABC\) se llaman congruentes (se puede escribir como\(\triangle A'B'C' \cong \triangle ABC\)) si hay un movimiento\(f: \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{X}\) tal que

\(A' = f(A)\),\(B' = f(B)\) y\(C' = f(C)\).

Dejar\(\mathcal{X}\) ser un espacio métrico, y\(f, g: \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{X}\) ser dos movimientos. Tenga en cuenta que la inversa\(f^{-1}: \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{X}\), así como la composición también\(f \circ g: \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{X}\) son movimientos.

De ello se deduce que\(\cong\) "" es una relación de equivalencia; es decir, cualquier triángulo congruente consigo mismo, y mantienen las dos condiciones siguientes:

- Si\(\triangle A'B'C' \cong \triangle ABC\), entonces\(\triangle ABC \cong \triangle A'B'C'\).

- Si\(\triangle A''B''C'' \cong \triangle A'B'C'\) y\(\triangle A'B'C' \cong \triangle ABC\), entonces

\[\triangle A''B''C'' \cong \triangle ABC.\]

Tenga en cuenta que si\(\triangle A'B'C' \cong \triangle ABC\), entonces\(AB = A'B', BC = B'C'\) y\(CA = C'A'\).

Para una métrica discreta, así como algunas otras métricas, también se mantiene la inversa. El siguiente ejemplo muestra que no se sostiene en el avión de Manhattan:

Considera tres puntos\(A = (0, 1), B = (1, 0)\), y\(C = (-1, 0)\) en el avión de Manhattan\((\mathbb{R}^2, d_1)\). Tenga en cuenta que

\[d_1 (A, B) = d_1 (A, C) = d_1 (B, C) = 2.\]

Por un lado,

\(\triangle ABC \cong \triangle ACB.\)

En efecto, el mapa\((x, y) \mapsto (-x, y)\) es un movimiento de\((\mathbb{R}^2, d_1)\) que envía\(A \mapsto A, B \mapsto C\), y\(C \mapsto B\).

Por otra parte,

\(\triangle ABC \not\cong \triangle BCA.\)

En efecto, argumentando por contradicción, supongamos que\(\triangle ABC \cong \triangle BCA\); es decir, hay una moción\(f\) de\((\mathbb{R}^2, d_1)\) ese mandar\(A \mapsto B, B \mapsto C,\) y\(C \mapsto A\).

Decimos que\(M\) es un punto medio de\(A\) y\(B\) si

\(d_1(A, M) = d_1(B, M) = \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot d_1(A, B).\)

Tenga en cuenta que un punto\(M\) es un punto medio de\(A\) y\(B\) si y solo si\(f(M)\) es un punto medio de\(B\) y\(C\).

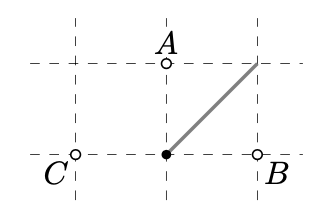

El conjunto de puntos medios para\(A\) y\(B\) es infinito, contiene todos los puntos\((t, t)\) para\(t \in [0, 1]\) (es el segmento gris en la imagen de arriba). Por otro lado, el punto medio para\(B\) y\(C\) es único (es el punto negro en la imagen). Así, el mapa\(f\) no puede ser biyective —una contradicción.