9.6: Medias líneas tangentes

- Page ID

- 114814

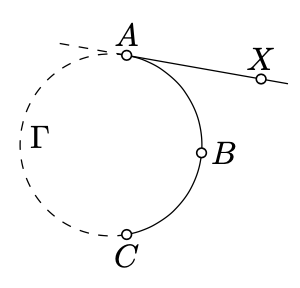

Supongamos que\(ABC\) es un arco de círculo\(\Gamma\). Una media línea\([AX)\) se llama tangente al arco\(ABC\) en\(A\) si la línea\((AX)\) es tangente a\(\Gamma\), y los puntos\(X\) y se\(B\) encuentran en el mismo lado de la línea\((AC)\).

Si el arco está formado por el segmento de línea\([AC]\), entonces la media línea\([AC)\) se considera tangente en\(A\). Si el arco está formado por una unión de dos medias líneas\([AX)\) y\([BY)\) adentro\((AC)\), entonces la media línea\([AX)\) se considera tangente al arco en\(A\).

La media línea\([AX)\) es tangente al arco\(ABC\) si y solo si

\(\measuredangle ABC + \measuredangle CAX \equiv \pi\).

- Prueba

-

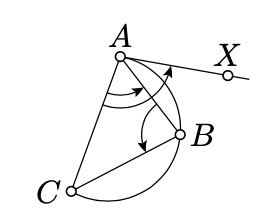

Para un arco degenerado\(ABC\), la afirmación es evidente. Además asumimos que el arco no\(ABC\) es degenerado.

Aplicando el Teorema 9.1.1 y el Teorema 9.2.1, obtenemos que

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle ABC + 2 \cdot \measuredangle CAX \equiv 0\).

Por lo tanto, ya sea

\(\measuredangle ABC + \measuredangle CAX \equiv \pi\), o\(\measuredangle ABC + \measuredangle CAX \equiv 0\).

Ya que\([AX)\) es la tangente media línea al arco\(ABC, X\) y\(B\) se encuentran en el mismo lado de\((AC)\). Por Corolario 3.4.1 y Teorema 3.3.1, los ángulos\(CAX\),\(CAB\), y\(ABC\) tienen el mismo signo. En particular,\(\measuredangle ABC + \measuredangle CAX \not\equiv 0\); es decir, nos quedamos con el caso

\(\measuredangle ABC +\measuredangle CAX \equiv \pi\).

Mostrar que hay un arco único con puntos finales en los puntos dados\(A\) y\(C\), que es tangente a la media línea dada\([AX)\) en\(A\).

- Pista

-

Si\(C \in (AX)\), entonces el arco es el segmento de línea\([AC]\) o la unión de dos medias líneas\((AX)\) con vértices en\(A\) y\(C\).

Asumir\(C \not\in (AX)\). Dejar\(\ell\) ser la línea perpendicular caída de\(A\) a\((AX)\) y\(m\) ser la bisectriz perpendicular de\([AC]\).

Tenga en cuenta que\(\ell \nparallel m\); establecer\(O = \ell \cap m\). Tenga en cuenta que el círculo con centro que\(O\) pasa a través también\(A\) está pasando a través\(C\) y tangente a\((AX)\).

Tenga en cuenta que uno de los dos arcos con puntos finales\(A\) y\(C\) es tangente a\([AX)\).

La singularidad se desprende de la Proposición\(\PageIndex{1}\).

Dejar\([AX)\) ser la media línea tangente a un arco\(ABC\). Supongamos que\(Y\) es un punto en el arco\(ABC\) que es distinto de\(A\). \(\measuredangle XAY \to 0\)Demuéstralo como\(AY \to 0\).

- Pista

-

Usa Proposición\(\PageIndex{1}\) y Teorema 7.4.1 para demostrarlo\(\measuredangle XAY = \measuredangle ACY\). Por Axioma IIIc,\(\measuredangle ACY \to 0\) como\(AY \to 0\); de ahí el resultado.

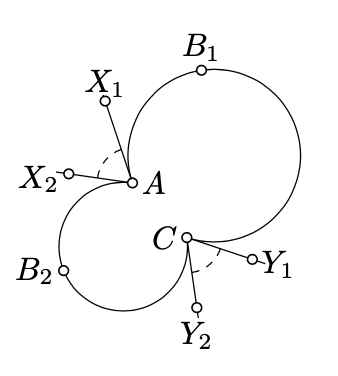

Dados dos arcos de círculo\(AB_1C\) y\(AB_2C\), dejar\([AX_1)\) y\([AX_2)\) en\(A\),\([CY_1)\) y\([CY_2)\) ser las medias líneas tangentes a los arcos\(AB_1C\) y\(AB_2C\) en\(C\). Demostrar que

\(\measuredangle X_1AX_2 \equiv -\measuredangle Y_1CY_2.\)

- Pista

-

Aplicar Proposición\(\PageIndex{1}\) dos veces.

(Alternativamente, aplicar Corolario 5.4.1 para la reflexión a través de la bisectriz perpendicular de\([AC]\).)