13.6: Teorema de Pitágoras

- Page ID

- 114325

Recordemos que\(\cosh\) denota coseno hiperbólico; es decir, la función definida por

\(\cosh x := \dfrac{e^x+e^{-x}}2.\)

Supongamos que\(ACB\) es un triángulo h con ángulo recto en\(C\). Set

\(a = BC_h,\)\(b = CA_h\)y\(c = AB_h\).

Entonces

\[\cosh c = \cosh a \cdot \cosh b.\]

La fórmula 13.6.1 se probará mediante cálculos directos. Antes de dar la prueba, discutamos los casos límite de esta fórmula.

Tenga en cuenta que se\(\cosh x\) puede escribir usando la expansión Taylor

\(\cosh x=1+\dfrac{1}{2}\cdot x^2+\dfrac{1}{24}\cdot x^4+\dots.\)

De ello se deduce que si\(a\)\(b\),, y\(c\) son pequeños, entonces

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {1 + \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot c^2} & \approx & {\cosh c = \cosh a \cdot \cosh b \approx} \\ {} & \approx & {(1 + \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot a^2)(1 + \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot b^2) \approx} \\ {} & \approx & {1 + \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot (a^2 + b^2).} \end{array}\)

En otras palabras, el teorema original de Pitágoras (Teorema 6.2.1) es un caso límite del teorema de Pitágoras hiperbólico para triángulos pequeños.

Para grandes\(a\) y\(b\) los términos\(e^{-a}\),\(e^{-b}\), y\(e^{-a-b+\ln 2}\) son negables. En este caso tenemos las siguientes aproximaciones:

\(\begin{array} {\cosh a \cdot \cos h b} & \approx & {\dfrac{e^a}{2} \cdot \dfrac{e^b}{2} =} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{e^{a+b-\ln 2}}{2} \approx} \\ {} & \approx & {\cosh (a+b-\ln 2)} \end{array}\)

Por lo tanto\(c \approx a+b-\ln 2\).

Supongamos que\(ACB\) es un triángulo h con ángulo recto en\(C\). Establecer\(a=BC_h\),\(b=CA_h\), y\(c=AB_h\). Demostrar que

\(c+\ln 2>a+b.\)

- Pista

-

Aplicar el teorema de Pitágoras hiperbólicas y la definición de coseno hiperbólico. Las siguientes observaciones deberían ayudar:

- \(x \mapsto e^x\)es una función positiva creciente.

- Por la desigualdad triangular, tenemos\(-c \le a - b\) y\(-c \le b - a\)

En la prueba del teorema hiperbólico de Pitágoras utilizamos la siguiente fórmula del Ejercicio 12.9.2:

aquí\(A\),\(B\) son los puntos h distintos del centro del absoluto y\(A'\),\(B'\) son sus inversiones en el absoluto. Esta fórmula se deriva en las pistas.

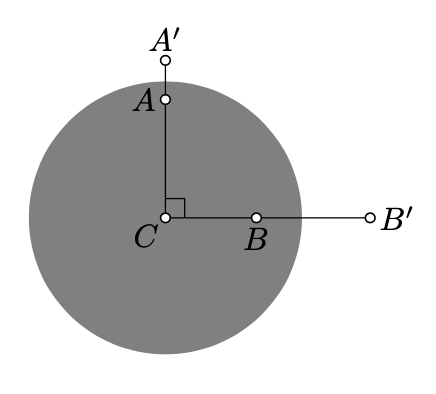

Prueba de Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\). Suponemos que absoluto es un círculo unitario. Por la observación principal (Teorema 12.3.1) podemos suponer que\(C\) es el centro de lo absoluto. Dejar\(A'\) y\(B'\) denotar las inversas de\(A\) y\(B\) en lo absoluto.

Establecer\(x=BC\),\(y=AC\). Por el Teorema de Lemma 12.3.2

\(a = \ln \dfrac{1 + x}{1 - x}\),\(b = \ln \dfrac{1 + y}{1 - y}.\)

Por lo tanto

\[\begin{array} {rclcrcl} {\cosh a} & = & {\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot (\dfrac{1 + x}{1 - x} + \dfrac{1 - x}{1 + x}) =} & \ \ \ \ & {\cosh b} & = & {\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot (\dfrac{1 + y}{1 - y} + \dfrac{1 - y}{1 + y}) =} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{1 + x^2}{1-x^2},} & \ \ \ \ & {} & = & {\dfrac{1 + y^2}{1 - y^2}.} \end{array}\]

Tenga en cuenta que

\(B'C = \dfrac{1}{x},\)\(A'C = \dfrac{1}{y}.\)

Por lo tanto

\(BB' = \dfrac{1}{x} - x\),\(AA' = \dfrac{1}{y} - y.\)

Dado que los triángulos\(ABC\),\(A'BC\),\(AB'C\),\(A'B'C\) tienen razón, el teorema pitagorano original (Teorema 6.2.1) implica

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {AB} & = & {\sqrt{x^2 + y^2}} \\ {A'B} & = & {\sqrt{x^2 + \dfrac{1}{y^2}},} \end{array}\)\(\begin{array} {rcl} {AB'} & = & {\sqrt{\dfrac{1}{x^2} + y^2,}} \\ {A'B'} & = & {\sqrt{\dfrac{1}{x^2} + \dfrac{1}{y^2}}.} \end{array}\)

Según el Ejercicio 12.9.2,

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\cosh c} & = & {\dfrac{AB \cdot A'B' + AB' \cdot A'B}{AA' \cdot BB'} = } \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{\sqrt{x^2 + y^2} \cdot \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{x^2} + \dfrac{1}{y^2}} + \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{x^2} + y^2} \cdot \sqrt{x^2 + \dfrac{1}{y^2}}}{(\dfrac{1}{y} - y) \cdot (\dfrac{1}{x} - x)} =} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{x^2 + y^2 + 1 + x^2 \cdot y^2}{(1 - y^2) \cdot (1 - x^2)} =} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{1 + x^2}{1 - x^2} \cdot \dfrac{1 + y^2}{1 - y^2}.} \end{array}\]

Por último señalar que 13.6.2 y 13.6.3 implican 13.6.1.