7.6: Área de un Círculo

- Page ID

- 114774

En el capítulo VI definimos el área de una cifra cerrada como el número de unidades cuadradas contenidas en la figura. Para aplicar esta definición al círculo, de nuevo asumiremos que un círculo es un polígono regular con un gran número de lados. A continuación se obtiene la siguiente fórmula:

El área del círculo es\(\pi\) multiplicada por el cuadrado de su radio.

\[A = \pi r^2\]

- Prueba

-

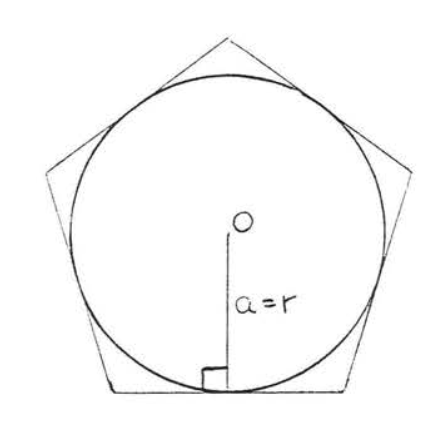

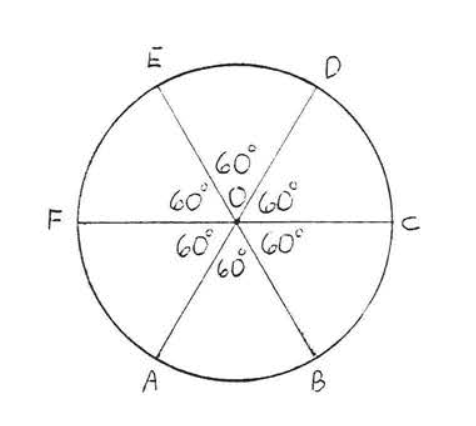

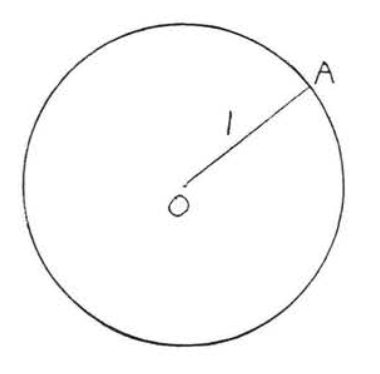

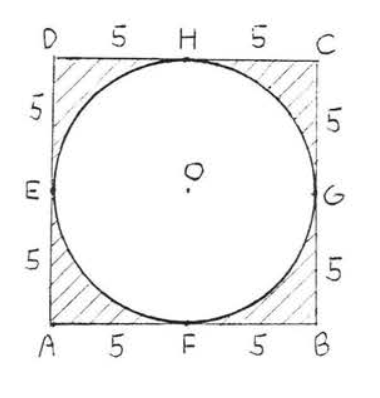

El área de un círculo con radio\(r\) es aproximadamente igual al área de un polígono regular con apotema\(a =r\) circunscrito alrededor del círculo (Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\)). La aproximación se vuelve más exacta a medida que aumenta el número de lados del polígono. Al mismo tiempo el perímetro del polígono se aproxima a la circunferencia del círculo (=\(2\pi r\)).

Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\): Polígono regular con apotema\(a = r\) circunscrito alrededor de círculo con radio\(r\).

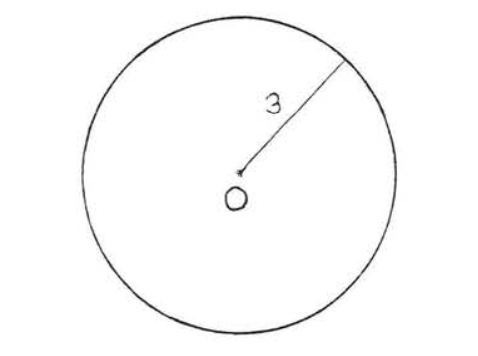

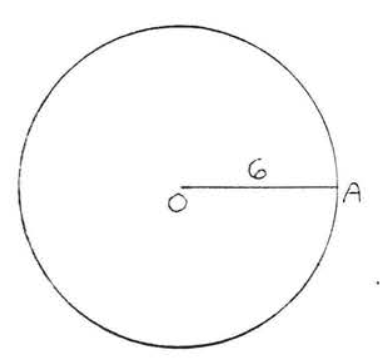

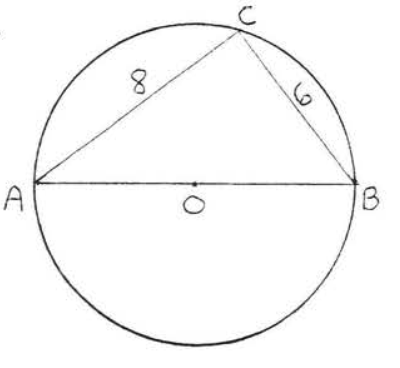

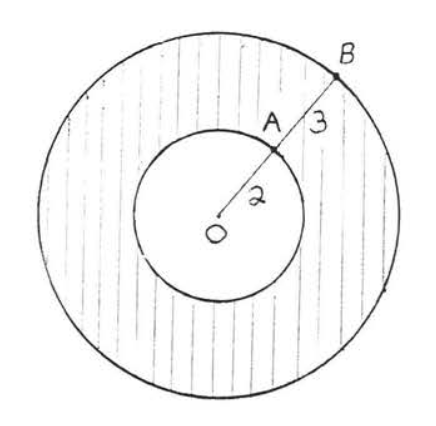

Encuentra el área del círculo:

Solución

\(A = \pi r^2 = \pi (3)^2 = 9\pi = 9(3.14) = 28.26\)

Respuesta: 28.26

Usando la fórmula para el área de un polígono regular (Teorema 7.1.4, sección 7.1) tenemos

\[\text{area of circle} = \text{area of polygon} = \dfrac{1}{2}aP = \dfrac{1}{2} r(2\pi r) = \pi r^2.\]

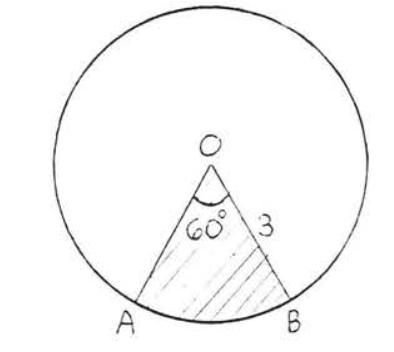

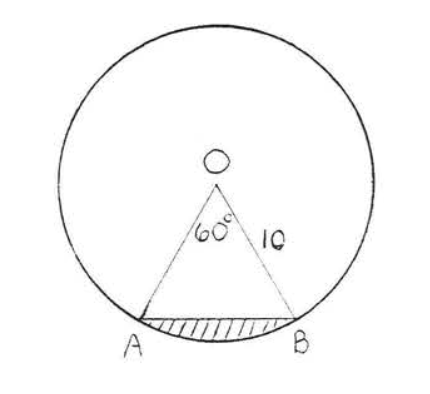

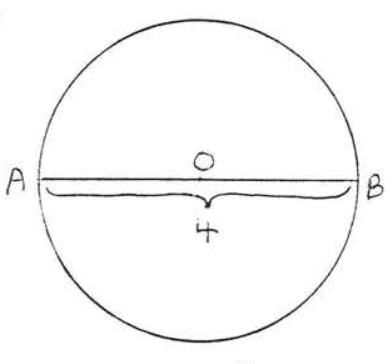

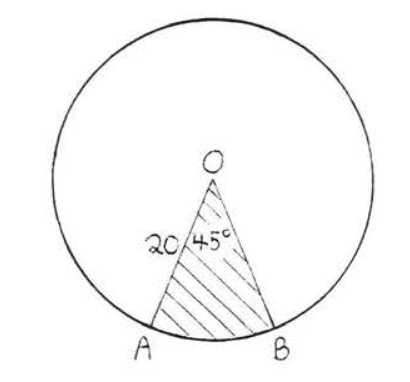

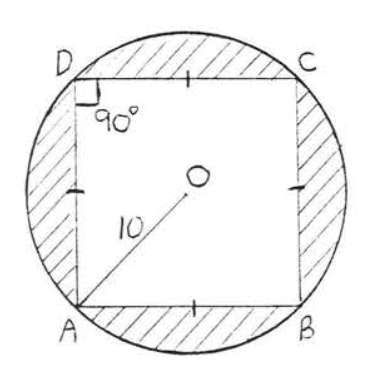

Encuentra el área sombreada:

Solución

El área sombreada\(OAB\) es\(\dfrac{60}{360} = \dfrac{1}{6}\) del área total (ver Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\)). El área de todo el círculo =\(\pi r^2 = \pi (3)^2 = 9\pi = 9(3.14) = 28.26\). Por lo tanto, el área de\(OAB = \dfrac{1}{6} (28.26) = 4.71\).

Respuesta: 4.71

El área sombreada en Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{2}\) se llama sector del círculo. Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{2}\) sugiere la siguiente fórmula para el área de un sector:

\[\text{Area of sector} = \dfrac{\text{Degrees in arc of sector}}{360} \cdot \text{Area of circle}\]

o simplemente

\[A = \dfrac{D}{360} \pi r^2\]

Usando esta fórmula, la solución del Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{2}\) sería

\[A = \dfrac{D}{360} \pi r^2 = \dfrac{60}{360} (3.14)(3)^2 = \dfrac{1}{6} (3.14)(9) = \dfrac{1}{6} (28.26) = 4.71\]

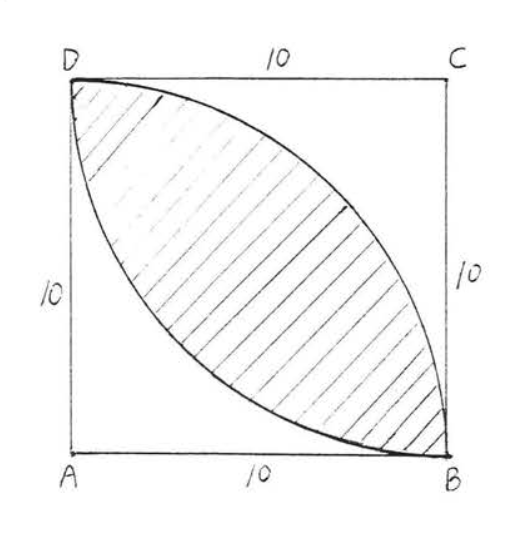

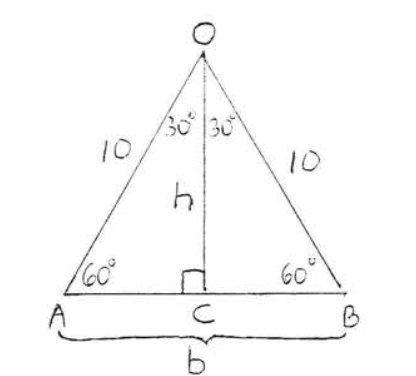

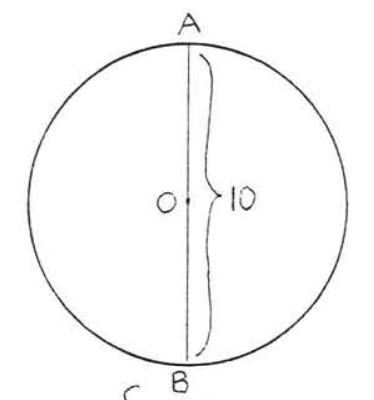

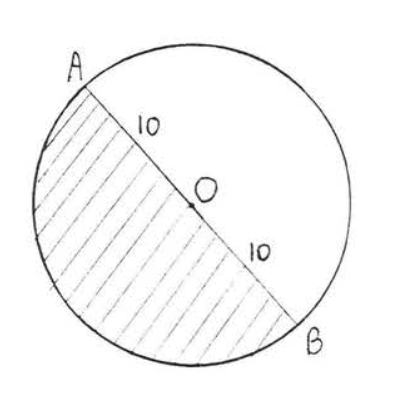

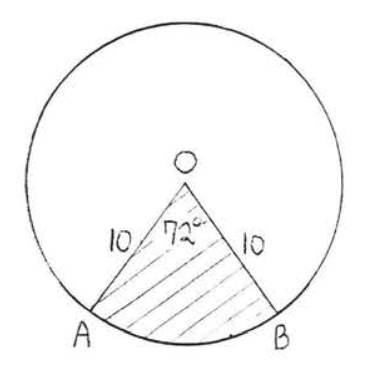

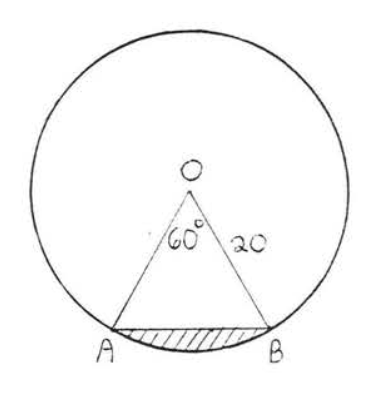

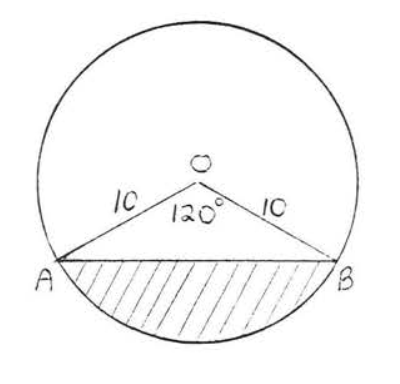

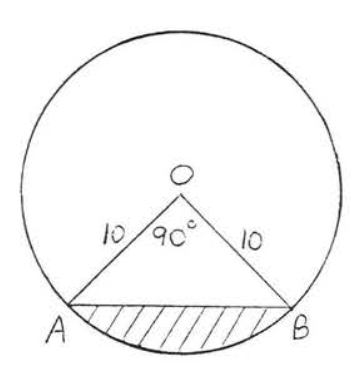

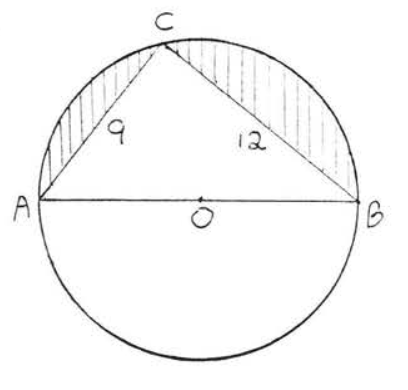

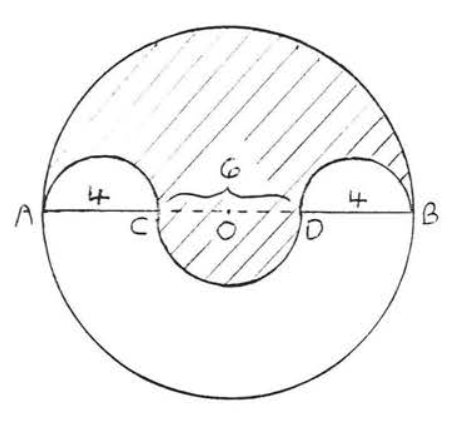

Encuentra el área sombreada:

Solución

Primero encontremos el área del triángulo\(OAB\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\)).

\(\triangle OAB\)es equilátero con base\(b = AB = 10\). Dibujando en altura\(h = OC\) tenemos que\(\triangle AOC\) es un\(30^{\circ} - 60^{\circ} -90^{\circ}\) triángulo con\(AC = 5\) y\(h = 5\sqrt{3}\). Por lo tanto área de\(\triangle OAB = \dfrac{1}{2} bh = \dfrac{1}{2} (10) (5\sqrt{3}) = 25 \sqrt{3}\). Por lo tanto

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\text{shaded area}} & = & {\text{area of sector } OAB - \text{area of triangle } OAB} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{D}{360} \pi r^2 - \dfrac{1}{2} bh} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{60}{360} \pi (10)^2 - \dfrac{1}{2} (10) (5\sqrt{3})} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{1}{6} (100\pi) - \dfrac{1}{2} (50\sqrt{3})} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{50\pi}{3} - 25\sqrt{3}} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{50(3.14)}{3} - 25(1.732)} \\ {} & = & {52.33 - 43.30 = 9.03} \end{array}\]

Respuesta:\(\dfrac{50\pi}{3} - 25\sqrt{3}\) o 9.03.

El área sombreada en Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{3}\) se llama segmento del círculo. El área de un segmento se obtiene restando el área del triángulo del área del sector.

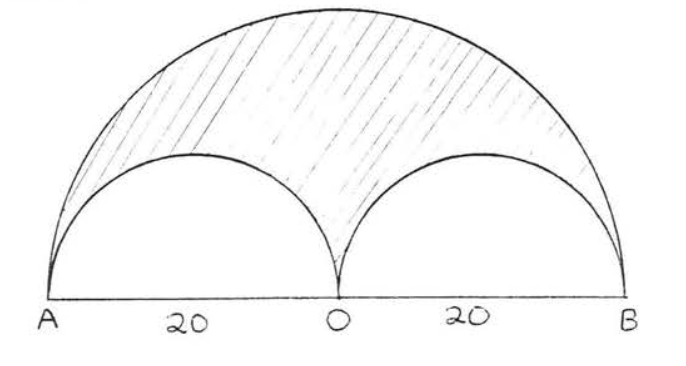

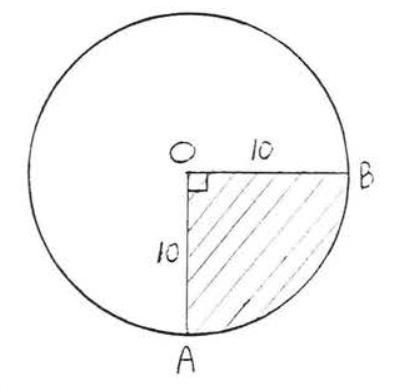

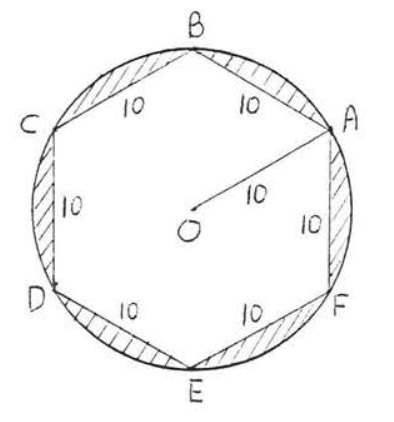

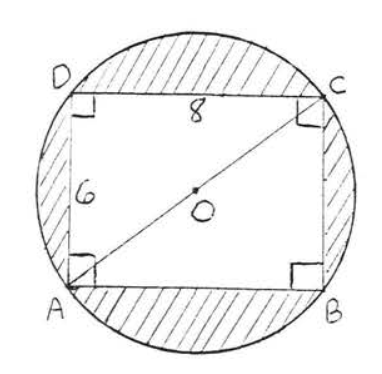

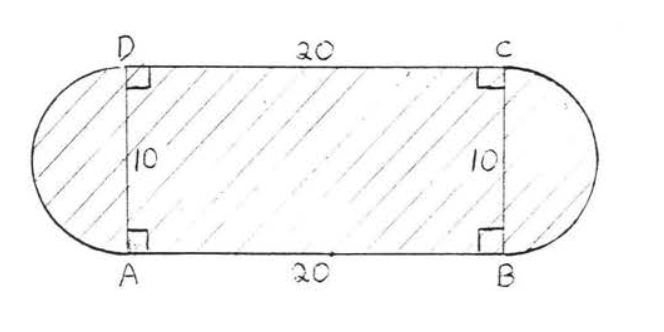

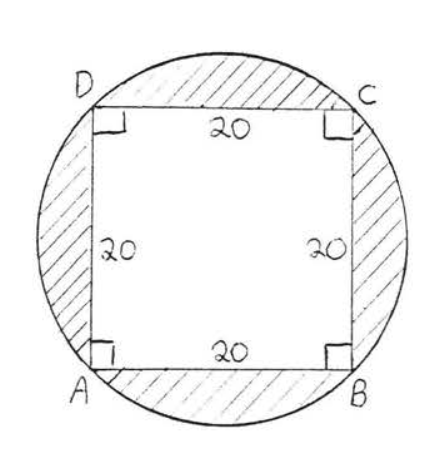

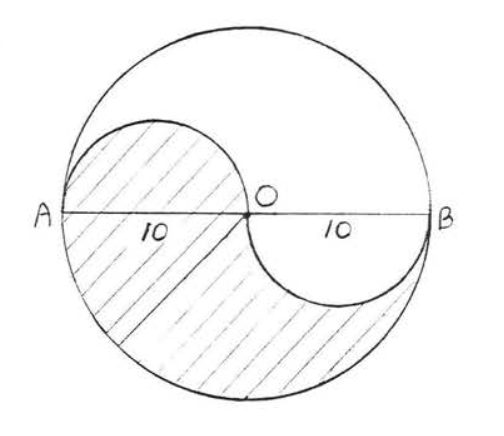

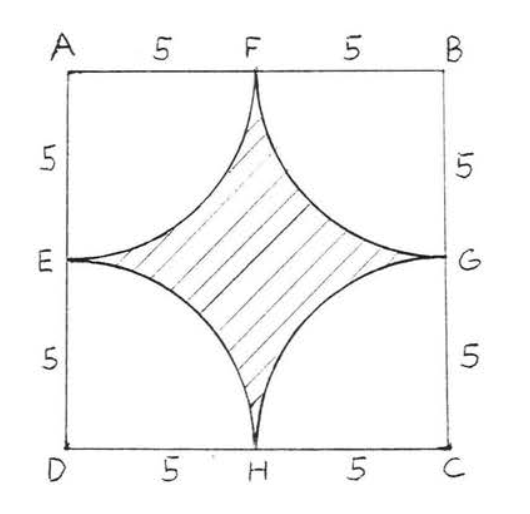

Encuentra el área sombreada:

Solución

El área del semicírculo grande =\(\dfrac{1}{2} \pi r^2 = \dfrac{1}{2} \pi (20)^2 = \dfrac{1}{2} (400) \pi = 200 \pi\). El área de cada uno de los semicírculos menores =\(\dfrac{1}{2} \pi r^2 = \dfrac{1}{2} \pi (10)^2 = \dfrac{1}{2} (100) \pi = 50\pi\). Por lo tanto

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\text{shaded area}} & = & {\text{area of large semicircle - (2)(area of small semicircles)}} \\ {} & = & {200 \pi - 2(50\pi)} \\ {} & = & {200\pi - 100\pi} \\ {} & = & {100 \pi = 100 (3.14) = 314} \end{array}\]

Respuesta:\(100 \pi\) o 314.

El problema 50 del Papiro Rbund, tratado matemático escrito por un escriba egipcio en aproximadamente 1650 a.C., establece que el área de un campo circular con un diámetro de 9 unidades es la misma que el área de un cuadrado con un lado de 8 unidades. Esto equivale a usar la fórmula\(A = (\dfrac{8}{9} d)^2\) para encontrar el área de un círculo. Si dejamos que\(d = 2r\) esto se convierta\(A = (\dfrac{8}{9} d)^2 = (\dfrac{8}{9} \cdot 2r)^2 = (\dfrac{16}{9} r)^2 = \dfrac{256}{81} r^2\) o sobre\(3.16 r^2\). Comparando esto con nuestra fórmula moderna\(A = \pi r^2\) encontramos que los antiguos egipcios tenían una aproximación notablemente buena, 3.16, por el valor de\(\pi\).

En la misma obra en la que calculó el valor de\(\pi\), Arquímedes da una fórmula para el área de un círculo (ver Nota Histórica, sección 7.5). Afirma que el área de un círculo es igual al área de un triángulo rectángulo cuya base\(b\) es tan larga como la circunferencia y cuya altitud\(h\) es igual al radio. Dejando\(b = C\) y\(h = r\) en la fórmula para el área de un triángulo, obtenemos\(A = \dfrac{1}{2} bh = \dfrac{1}{2} Cr = \dfrac{1}{2} (2\pi r) = \pi r^2\), la fórmula moderna.

PROBLEMAS

1 - 6. Encuentra el área del círculo (usa\(\pi = 3.14\)):

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7 - 10. Encuentra el área del círculo con... (uso\(\pi = 3.14\))

7. radio 20.

8. radio 2.5.

9. diámetro 12.

10. diámetro 15.

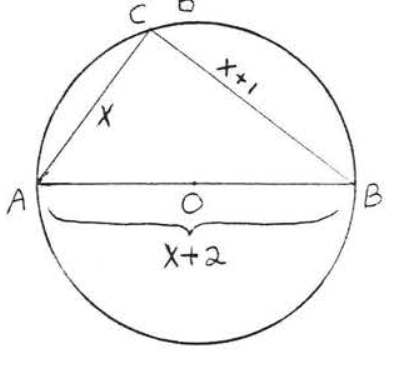

11 - 14. Encuentra el área sombreada (use\(\pi = 3.14\)):

11.

12.

13.

14.

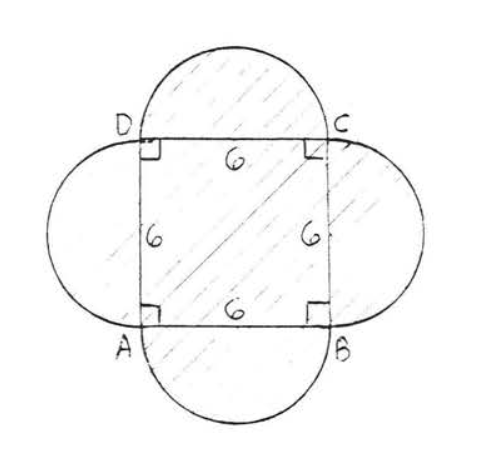

15 - 30. Encuentra el área sombreada. Las respuestas pueden dejarse en términos\(\pi\) y en forma radical.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.