14.3: Eliminación por los mecanismos E1 y E2

- Page ID

- 2421

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

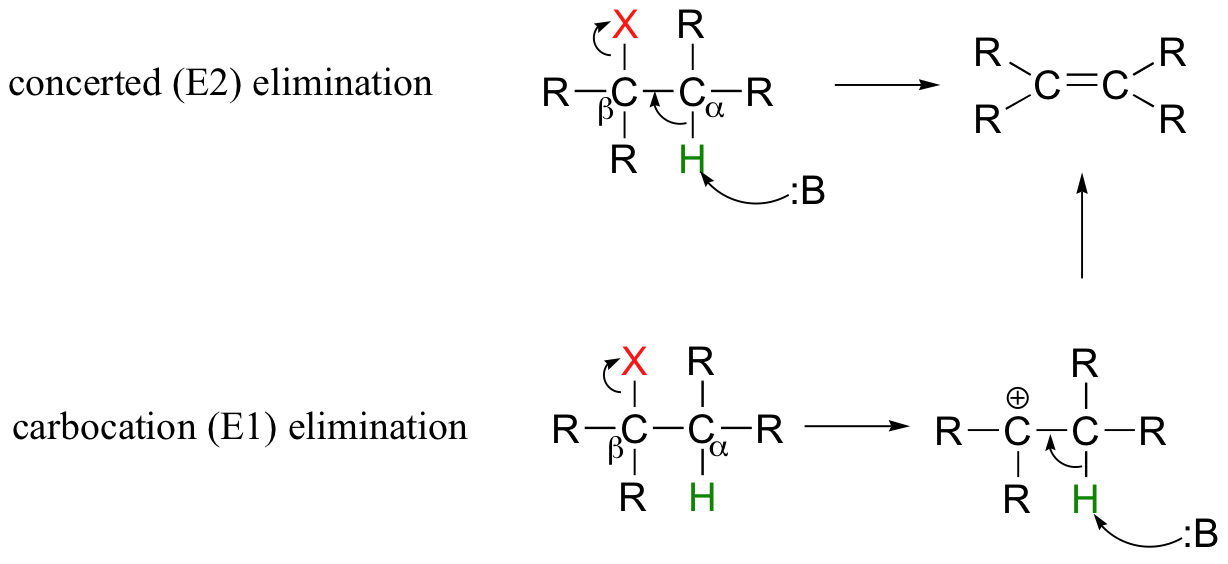

So far in this chapter, we have seen several examples of carbanion-intermediate (E1cb) beta-elimination reactions, in which the first step was proton abstraction at a carbon positioned ato an electron-withdrawing carbonyl or imine. Elimination reactions are also possible at positions that are isolated from carbonyls or any other electron-withdrawing groups. This type of elimination can be described by two model mechanisms: it can occur in a single concerted step (proton abstraction at Cα occurring at the same time as Cβ-X bond cleavage), or in two steps (Cβ-X bond cleavage occurring first to form a carbocation intermediate, which is then 'quenched' by proton abstraction at the alpha-carbon).

These mechanisms, termed E2 and E1, respectively, are important in laboratory organic chemistry, but are less common in biological chemistry. As explained below, which mechanism actually occurs in a laboratory reaction will depend on the identity of the R groups (ie., whether the alkyl halide is primary, secondary, tertiary, etc.) as well as on the characteristics of the base.

14.3A: E1 and E2 reactions in the laboratory

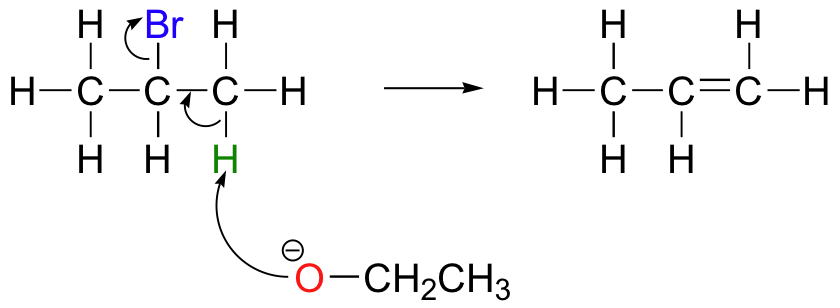

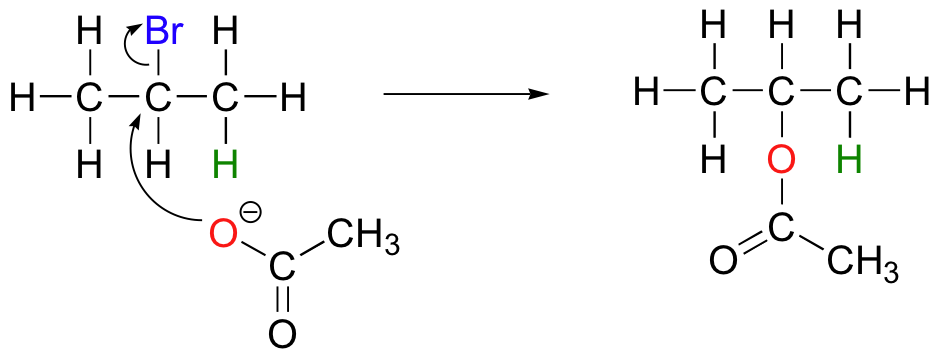

E2 elimination reactions in the laboratory are carried out with relatively strong bases, such as alkoxides (deprotonated alcohols). 2-bromopropane will react with ethoxide, for example, to give propene.

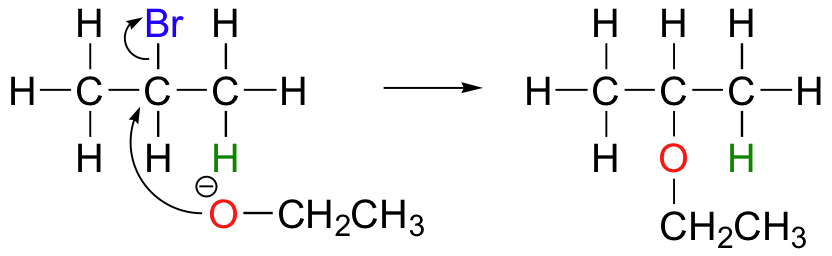

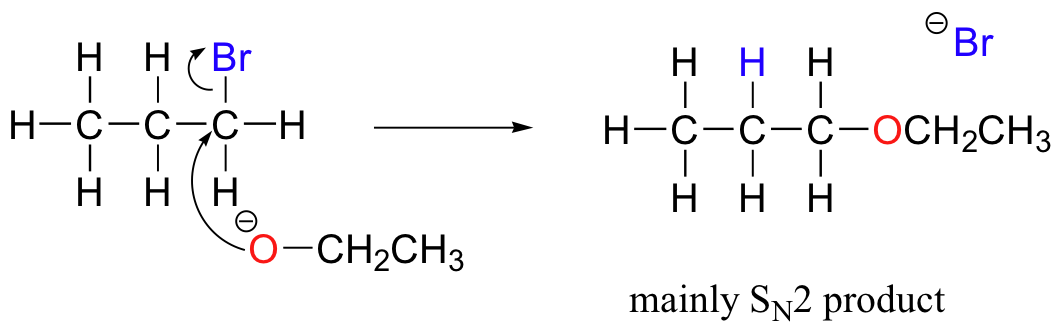

Propene is not the only product of this reaction, however - the ethoxide will also to some extent act as a nucleophile in an SN2 reaction.

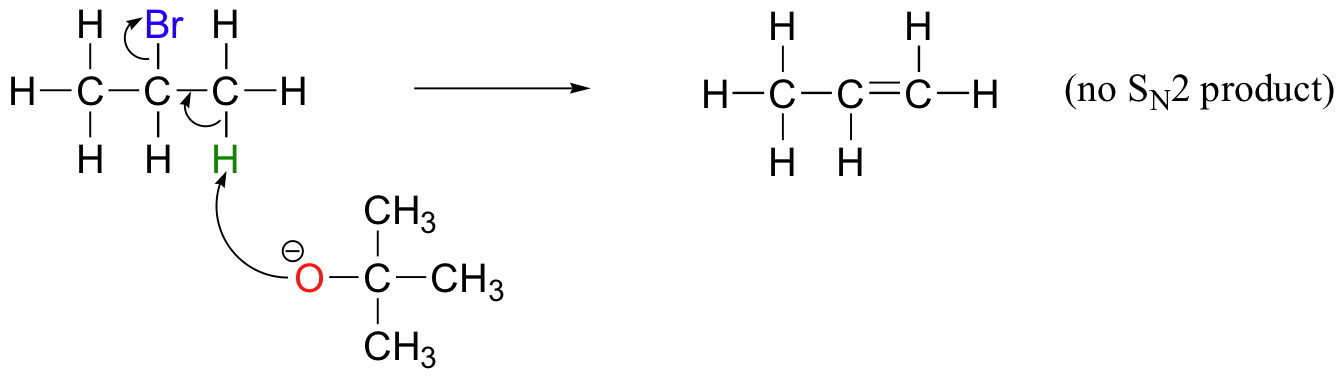

Chemists carrying out nonenzymatic nucleophilic substitution or elimination reactions always have to be aware of the competition between the two mechanisms, because bases can also be nucleophiles, and vice-versa. However, a chemist can tip the scales in one direction or another by carefully choosing reagents. Primary carbon electrophiles like 1-bromopropane, for example, are much more likely to undergo substitution (by the SN2 mechanism) than elimination (by the E2 mechanism) – this is because the electrophilic carbon is unhindered and a good target for a nucleophile.

SN1 and E1 mechanisms are unlikely with such compounds because of the relative instability of primary carbocations.

The nature of the electron-rich species is also critical. Acetate, for example, is a weak base but a reasonably good nucleophile, and will react with 2-bromopropane mainly as a nucleophile.

In order to direct the reaction towards elimination, a strong hindered base such as tert-butoxide can be used. The bulkiness of tert-butoxide makes it difficult for the oxygen to reach the carbon (in other words, to act as a nucleophile). It is more likely to pluck off a proton, which is much more accessible than the electrophilic carbon).

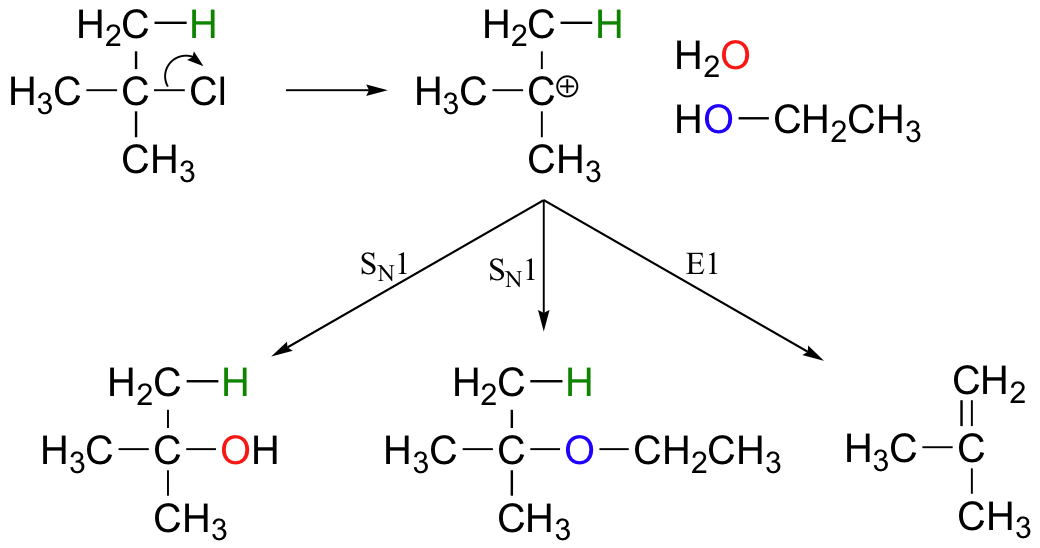

E1 reactions occur by the same kinds of carbocation-favoring conditions that have already been described for SN1 reactions (section 9.4): a secondary or tertiary substrate, a protic solvent, and a relatively weak base/nucleophile. In fact, E1 and SN1 reactions generally occur simultaneously, giving a mixture of substitution and elimination products after formation of a common carbocation intermediate. When tert-butyl chloride is stirred in a mixture of ethanol and water, for example, a mixture of SN1 products (tert-butyl alcohol and tert-butyl ethyl ether) and E1 product (2-methylpropene) results.

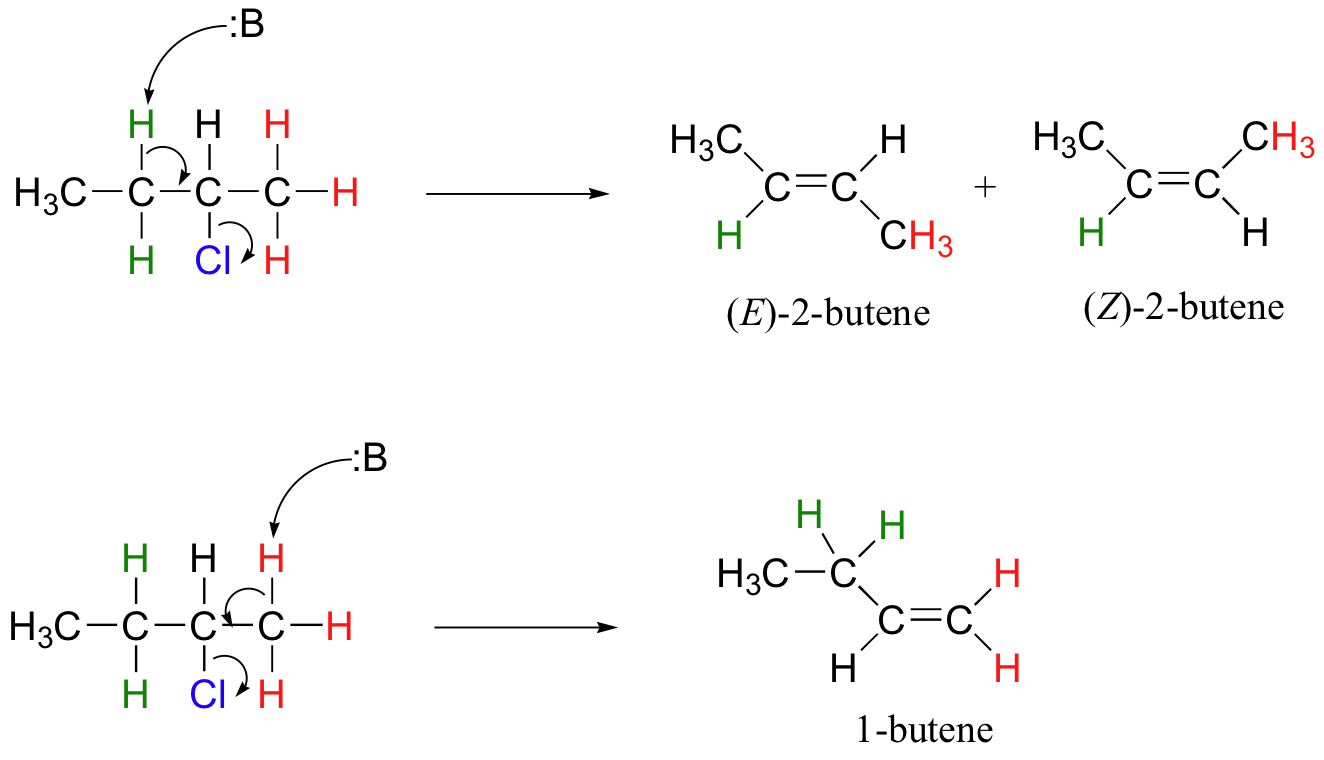

This reaction is both regiospecific and stereospecific. In general, more substituted alkenes are more stable, and as a result, the product mixture will contain less 1-butene than 2-butene (this is the regiochemical aspect of the outcome, and is often referred to as Zaitsev's rule). In addition, we already know that trans (E) alkenes are generally more stable than cis (Z) alkenes (section 3.7C), so we can predict that more of the E product will form compared to the Z product.

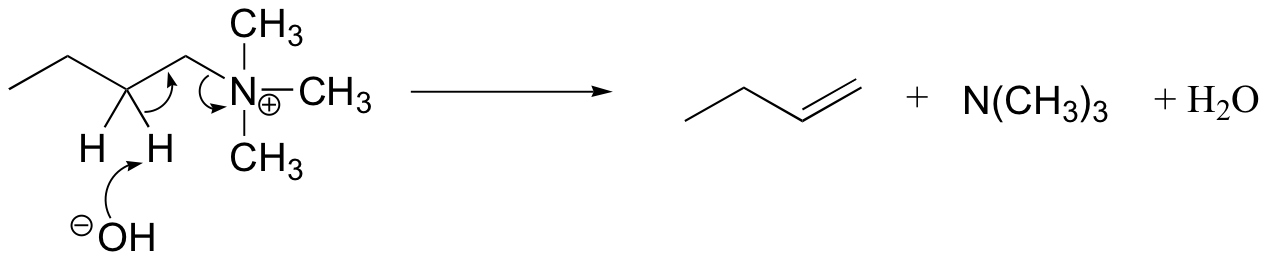

The Hoffman elimination is a well-studied E2 elimination in which the leaving group is a quaternary amine - note that there is no proton on the quaternary amine that could protonate the base in the reaction:

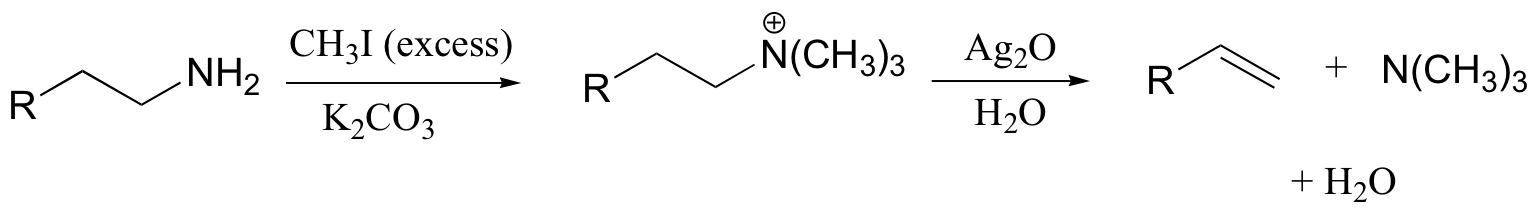

In practice, the quaternary amine is made by treating a primary or secondary amine with excess methyl iodide and weak base (this, of course, is an SN2 methylation reaction, covered in section 9.1B). Silver oxide in water generates the necessary hydroxide ion.

There is very little competing substitution under these conditions.

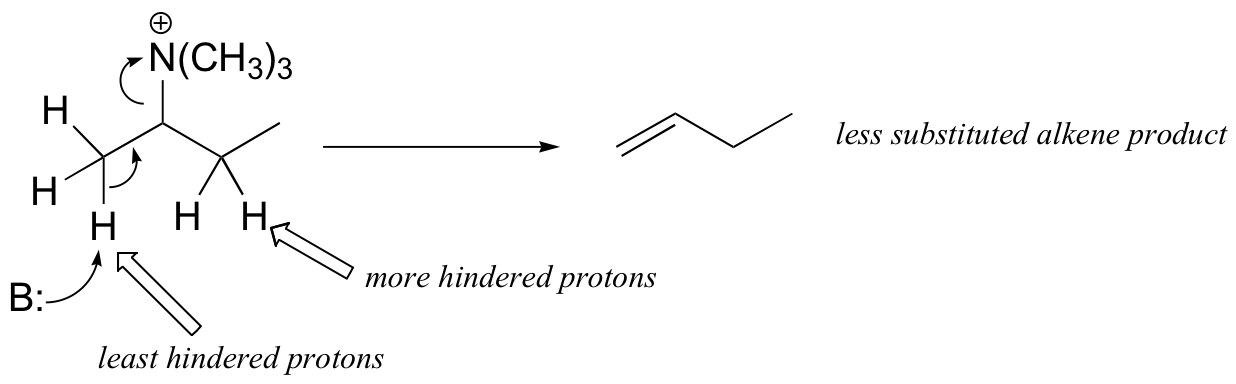

The Hoffman elimination is somewhat unique in that, unlike other elimination reactions, it is usually the least substituted alkene that is the predominant product. This is due to steric factors: the large size of the quaternary ammonium leaving group results in the most accessible (least hindered) proton being abstracted - meaning the proton from the least substituted carbon.

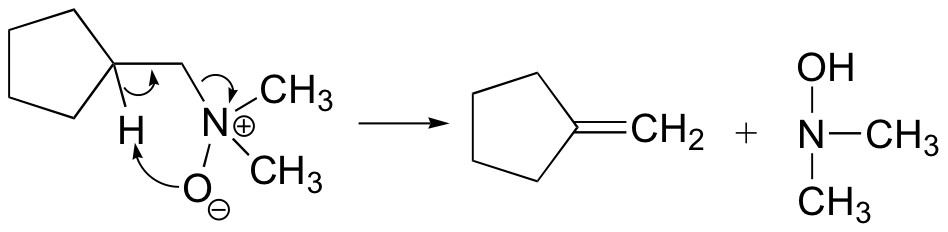

The Cope elimination is another well-known laboratory E2 reaction involving an amine oxide:

Notice that the leaving group is also the base. The transition state is thought to be planar (or close to it).

14.3B: Enzymatic E1 and E2 reactions

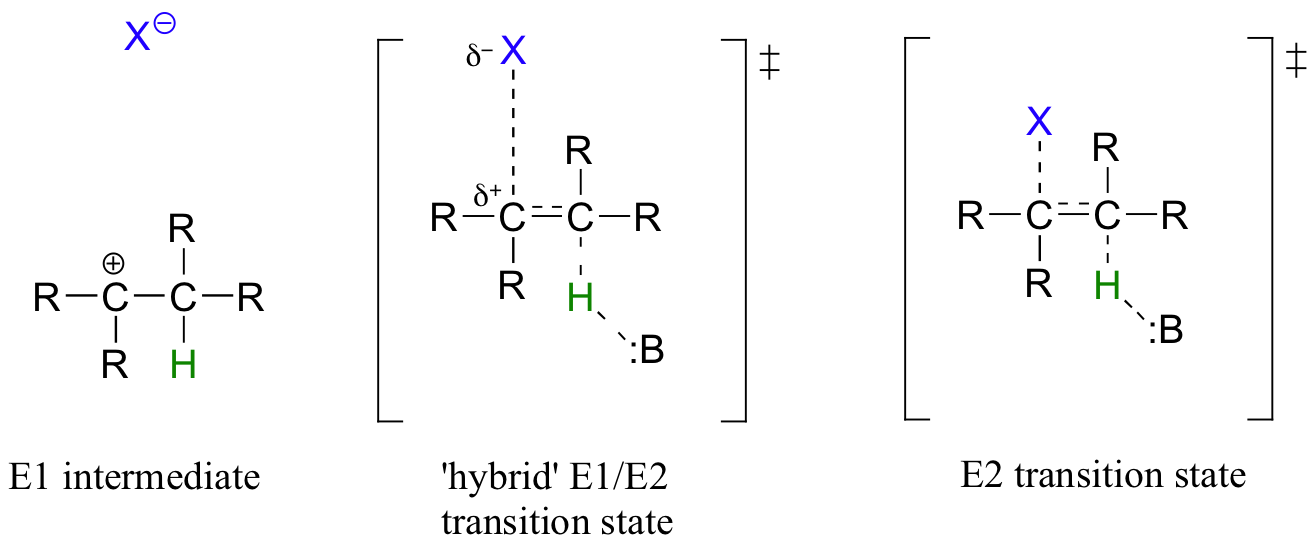

While most biochemical b-elimination reactions are of the E1cb type, some enzymatic E2 and E1 reactions are known. Like the enzymatic SN2 and SN1 substitution mechanisms discussed in chapters 8 and 9, the E2 and E1 models represent two possible mechanistic extremes, and actual enzymatic elimination reactions may fall somewhere in between. In an E1/E2 hybrid elimination, for example, Cβ-X bond cleavage may be quite advanced (but not complete) before proton abstraction takes place - this would lead to the build-up of transient partial positive charge on Cβ, but a discreet carbocation intermediate would not form. The extent to which partial positive charge builds up determines whether we refer to the mechanism as 'E1-like' or 'E2-like'.

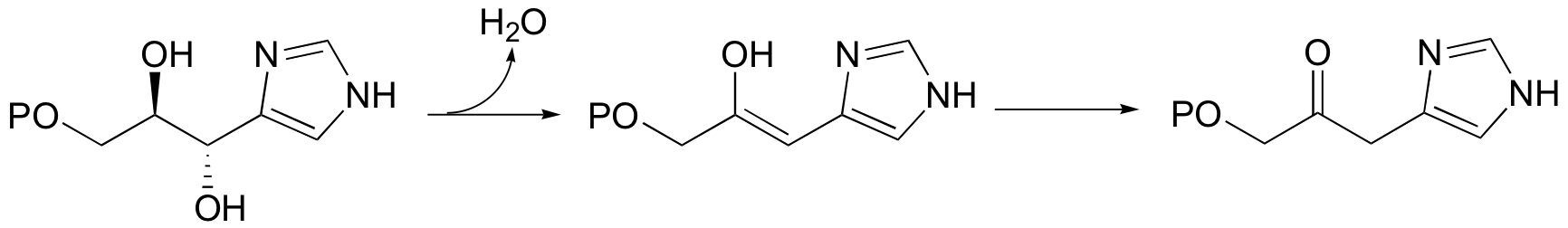

A reaction in the histidine biosynthetic pathway provides a good example of a biological E1-like elimination step (we're looking specifically here at the first, enol-forming step in the reaction below - the second step is simply a tautomerization from the enol to the ketone product (section 13.1A)).

Notice in this mechanism that an E1cb elimination is not possible - there is no electron-withdrawing group (like a carbonyl) to stabilize the carbanion intermediate that would form if the proton were abstracted first. There is, however, an electron-donating group (the lone pair on a nitrogen) that can stabilize a positively-charged intermediate that forms when the water leaves.

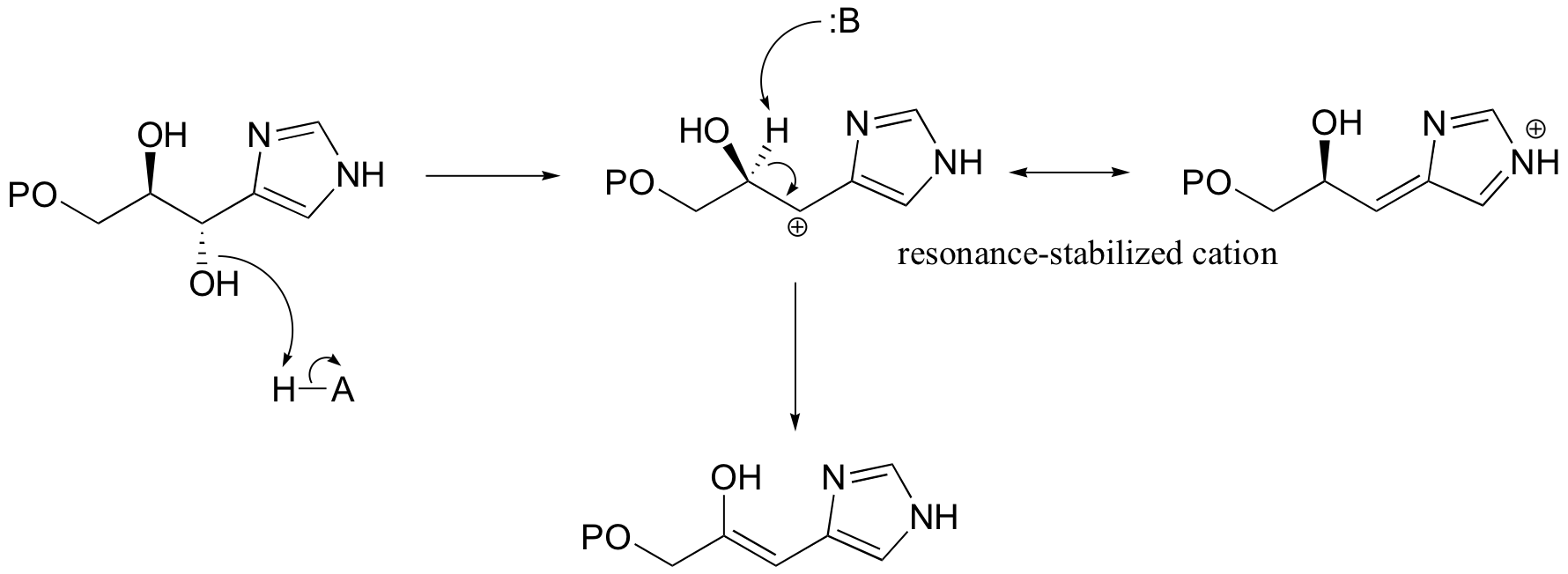

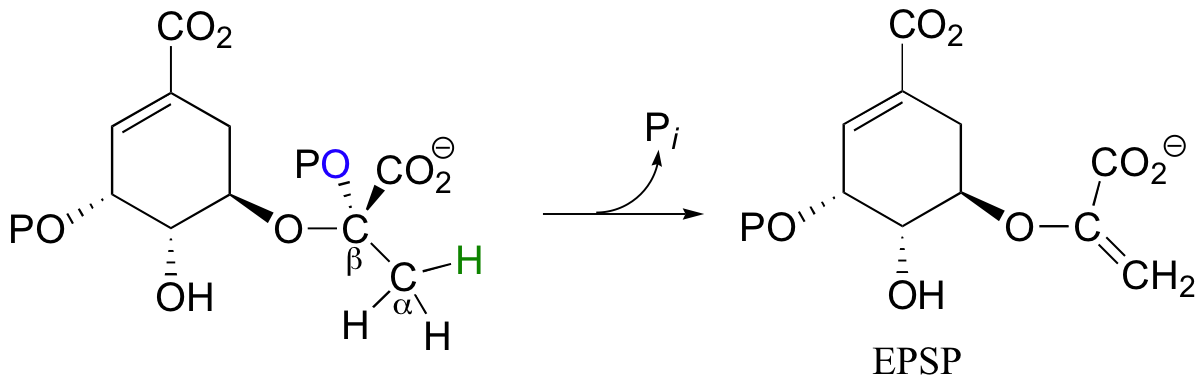

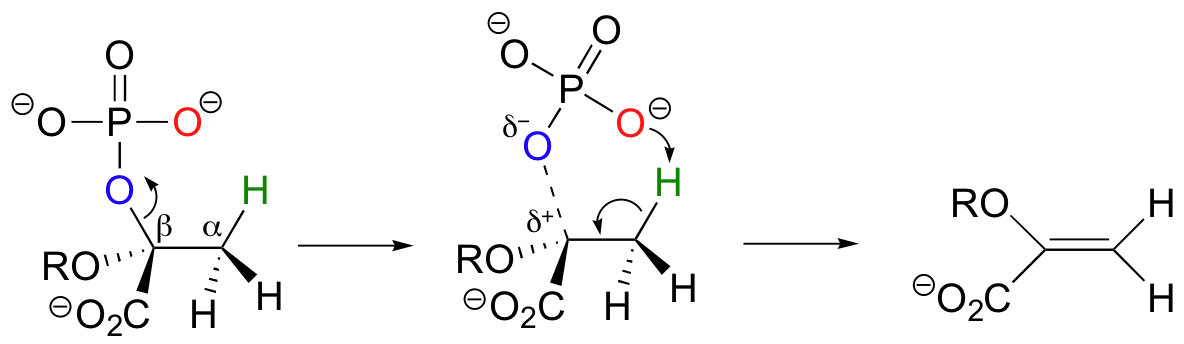

Another good example of a biological E1-like reaction is the elimination of phosphate in the formation of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP), an intermediate in the synthesis of aromatic amino acids.

Experimental evidence indicates that significant positive charge probably builds up on Cβ of the starting compound, implying that C-O bond cleavage is advanced before proton abstraction occurs (notice the parallels to the Cope elimination in the previous section):

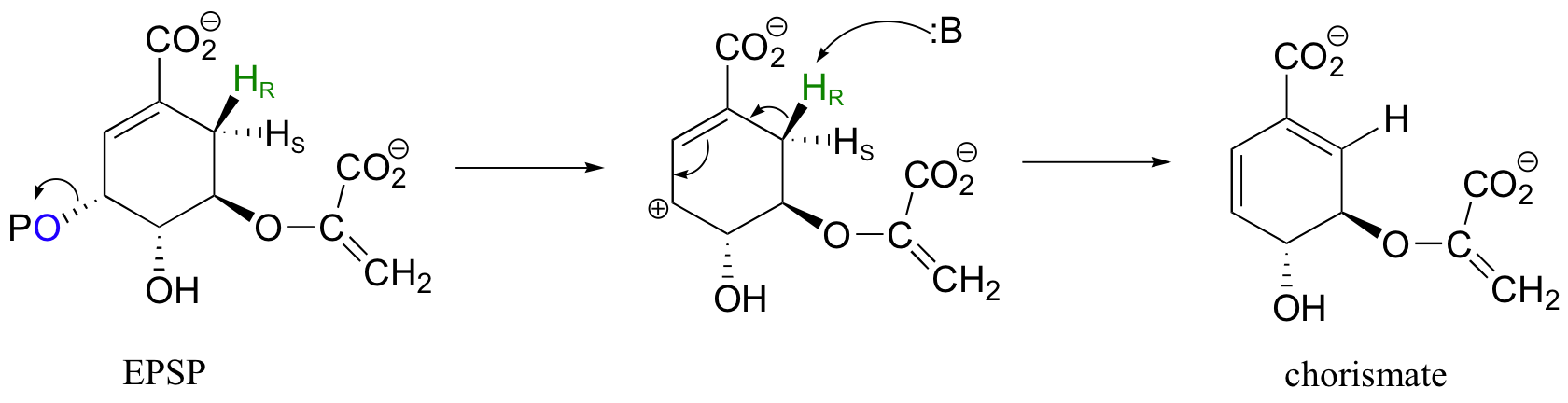

The very next step in the aromatic acid biosynthesis pathway is also an elimination, this time a 1,6-conjugated elimination rather than a simple beta-elimination.

An E1-like mechanism (as illustrated above) has been proposed for this step, but other evidence suggests that a free-radical mechanism may be involved. Free-radical mechanisms will be discussed in chapter 17.

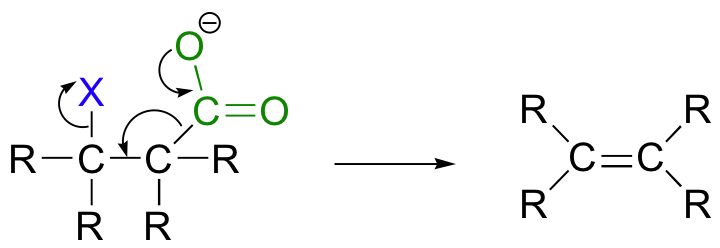

While most E1 and E2 reactions involve proton abstraction, eliminations can also incorporate a decarboxylation step.

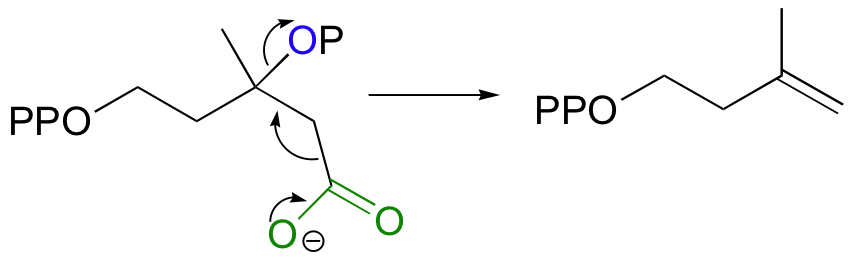

Isopentenyl diphosphate, the 'building block' for all isoprenoid compounds, is formed from a decarboxylation-elimination reaction.

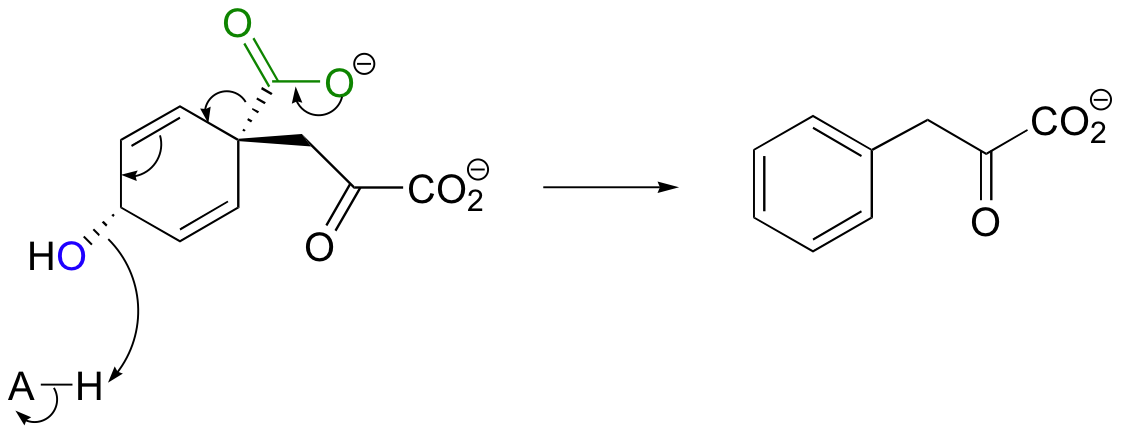

Phenylpyruvate, a precursor in the biosynthesis of phenylalanine, results from a conjugated 1,6 decarboxylation-elimination.

Two additional examples of E1-like steps in enzymatic reactions are illustrated in problem P14.8.