35.3: El Sistema Nervioso Central

- Page ID

- 59596

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Habilidades para Desarrollar

- Identificar la médula espinal, los lóbulos cerebrales y otras áreas cerebrales en un diagrama del cerebro

- Describir las funciones básicas de la médula espinal, los lóbulos cerebrales y otras áreas cerebrales

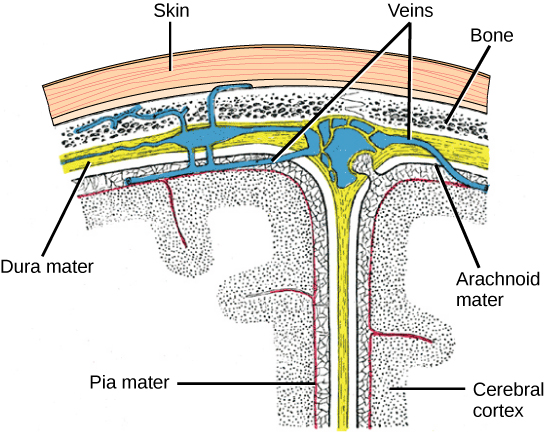

El sistema nervioso central (SNC) está formado por el cerebro, una parte del cual se muestra en la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) y la médula espinal y está cubierto con tres capas de cubiertas protectoras llamadas meninges (de la palabra griega para membrana). La capa más externa es la duramadre (latín para “madre dura”). Como sugiere el latín, la función principal de esta gruesa capa es proteger el cerebro y la médula espinal. La duramadre también contiene estructuras en forma de vena que transportan la sangre desde el cerebro hasta el corazón. La capa media es la materia aracnoidea similar a una tela. La última capa es la pia mater (en latín para “madre blanda”), que contacta directamente y cubre el cerebro y la médula espinal como una envoltura plástica. El espacio entre el aracnoideo y la piamadre se llena de líquido cefalorraquídeo (LCR). El LCR es producido por un tejido llamado plexo coroideo en compartimentos llenos de líquido en el SNC llamado ventrículos. El cerebro flota en el LCR, que actúa como cojín y amortiguador y hace que el cerebro flote de manera neutra. El LCR también funciona para hacer circular sustancias químicas por todo el cerebro y hacia la médula espinal.

Todo el cerebro contiene solo alrededor de 8.5 cucharadas de LCR, pero el LCR se produce constantemente en los ventrículos. Esto crea un problema cuando se obstruye un ventrículo: el LCR se acumula y crea hinchazón y el cerebro se empuja contra el cráneo. Esta afección de hinchazón se llama hidrocefalia (“cabeza de agua”) y puede causar convulsiones, problemas cognitivos e incluso la muerte si no se inserta una derivación para eliminar el líquido y la presión.

Cerebro

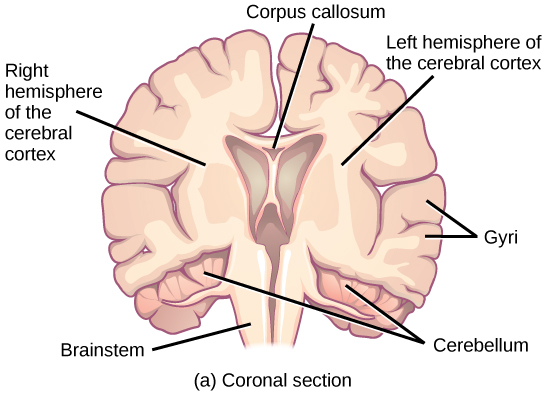

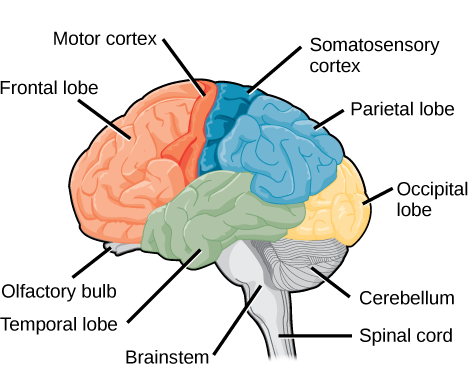

El cerebro es la parte del sistema nervioso central que está contenida en la cavidad craneal del cráneo. Incluye la corteza cerebral, el sistema límbico, los ganglios basales, el tálamo, el hipotálamo y el cerebelo. Hay tres formas diferentes de seccionar un cerebro para ver las estructuras internas: una sección sagital corta el cerebro de izquierda a derecha, como se muestra en la Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\) b, una sección coronal corta el cerebro de adelante hacia atrás, como se muestra en la Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\) a, y una sección horizontal corta el cerebro de arriba a abajo.

Corteza Cerebral

La parte más externa del cerebro es una gruesa pieza de tejido del sistema nervioso llamada corteza cerebral, que se pliega en colinas llamadas giratorias (singular: circunvolución) y valles llamados sulci (singular: surco). La corteza se compone de dos hemisferos, derecho e izquierdo, que están separados por un gran surco. Un haz grueso de fibras llamado cuerpo calloso (latín: “cuerpo duro”) conecta los dos hemisferios y permite que la información se pase de un lado a otro. Si bien hay algunas funciones cerebrales que se localizan más en un hemisferio que en el otro, las funciones de los dos hemisferios son en gran parte redundantes. De hecho, a veces (muy raramente) se extirpa un hemisferio completo para tratar la epilepsia grave. Si bien los pacientes sí sufren algunos déficits después de la cirugía, pueden tener sorprendentemente pocos problemas, especialmente cuando la cirugía se realiza en niños que tienen sistemas nerviosos muy inmaduros.

En otras cirugías para tratar la epilepsia severa, se corta el cuerpo calloso en lugar de extirpar todo un hemisferio. Esto provoca una condición llamada cerebro dividido, que da una idea de las funciones únicas de los dos hemisferios. Por ejemplo, cuando un objeto se presenta al campo visual izquierdo de los pacientes, es posible que no puedan nombrar verbalmente el objeto (y pueden afirmar que no han visto un objeto en absoluto). Esto se debe a que la entrada visual del campo visual izquierdo cruza y entra en el hemisferio derecho y no puede entonces señalar al centro del habla, que generalmente se encuentra en el lado izquierdo del cerebro. Sorprendentemente, si se le pide a un paciente de cerebro dividido que recoja un objeto específico de un grupo de objetos con la mano izquierda, el paciente podrá hacerlo pero aún así no podrá identificarlo vocalmente.

Enlace al aprendizaje

Consulta este sitio web para conocer más sobre los pacientes con cerebro dividido y jugar un juego en el que puedas modelar los experimentos de cerebro dividido tú mismo.

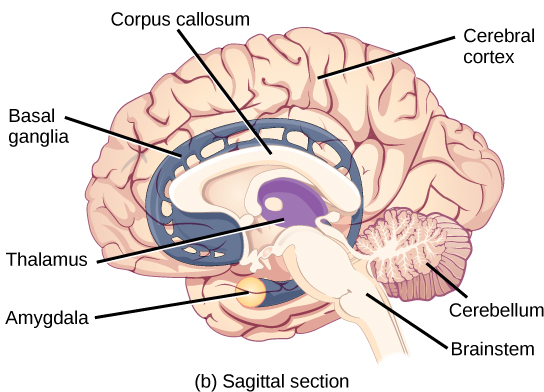

Cada hemisferio cortical contiene regiones llamadas lóbulos que están involucradas en diferentes funciones. Los científicos utilizan diversas técnicas para determinar qué áreas cerebrales están involucradas en diferentes funciones: examinan a pacientes que han tenido lesiones o enfermedades que afectan áreas específicas y ven cómo esas áreas se relacionan con déficits funcionales. También realizan estudios en animales donde estimulan áreas cerebrales y ven si hay algún cambio de comportamiento. Utilizan una técnica llamada estimulación transmagnética (TMS) para desactivar temporalmente partes específicas de la corteza usando imanes fuertes colocados fuera de la cabeza; y utilizan imágenes de resonancia magnética funcional (fMRI) para observar los cambios en el flujo sanguíneo oxigenado en regiones cerebrales particulares que se correlacionan con tareas conductuales específicas. Estas técnicas, y otras, han dado una gran comprensión de las funciones de diferentes regiones cerebrales pero también han demostrado que cualquier área cerebral dada puede estar involucrada en más de un comportamiento o proceso, y cualquier comportamiento o proceso dado generalmente involucra neuronas en múltiples áreas cerebrales. Dicho esto, cada hemisferio de la corteza cerebral de los mamíferos puede dividirse en cuatro lóbulos definidos funcional y espacialmente: frontal, parietal, temporal y occipital. Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\) illustrates these four lobes of the human cerebral cortex.

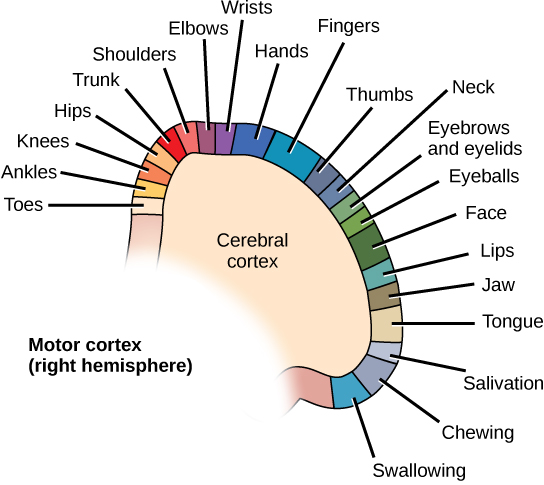

The frontal lobe is located at the front of the brain, over the eyes. This lobe contains the olfactory bulb, which processes smells. The frontal lobe also contains the motor cortex, which is important for planning and implementing movement. Areas within the motor cortex map to different muscle groups, and there is some organization to this map, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). For example, the neurons that control movement of the fingers are next to the neurons that control movement of the hand. Neurons in the frontal lobe also control cognitive functions like maintaining attention, speech, and decision-making. Studies of humans who have damaged their frontal lobes show that parts of this area are involved in personality, socialization, and assessing risk.

The parietal lobe is located at the top of the brain. Neurons in the parietal lobe are involved in speech and also reading. Two of the parietal lobe’s main functions are processing somatosensation—touch sensations like pressure, pain, heat, cold—and processing proprioception—the sense of how parts of the body are oriented in space. The parietal lobe contains a somatosensory map of the body similar to the motor cortex.

The occipital lobe is located at the back of the brain. It is primarily involved in vision—seeing, recognizing, and identifying the visual world.

The temporal lobe is located at the base of the brain by your ears and is primarily involved in processing and interpreting sounds. It also contains the hippocampus (Greek for “seahorse”)—a structure that processes memory formation. The hippocampus is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). The role of the hippocampus in memory was partially determined by studying one famous epileptic patient, HM, who had both sides of his hippocampus removed in an attempt to cure his epilepsy. His seizures went away, but he could no longer form new memories (although he could remember some facts from before his surgery and could learn new motor tasks).

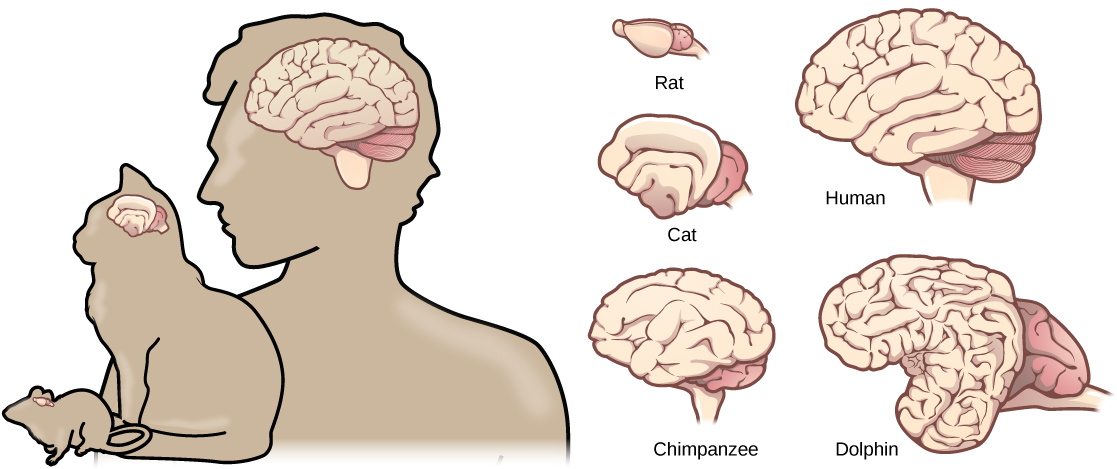

Evolution Connection: Cerebral Cortex

Compared to other vertebrates, mammals have exceptionally large brains for their body size. An entire alligator’s brain, for example, would fill about one and a half teaspoons. This increase in brain to body size ratio is especially pronounced in apes, whales, and dolphins. While this increase in overall brain size doubtlessly played a role in the evolution of complex behaviors unique to mammals, it does not tell the whole story. Scientists have found a relationship between the relatively high surface area of the cortex and the intelligence and complex social behaviors exhibited by some mammals. This increased surface area is due, in part, to increased folding of the cortical sheet (more sulci and gyri). For example, a rat cortex is very smooth with very few sulci and gyri. Cat and sheep cortices have more sulci and gyri. Chimps, humans, and dolphins have even more.

Basal Ganglia

Interconnected brain areas called the basal ganglia (or basal nuclei) play important roles in movement control and posture. Damage to the basal ganglia, as in Parkinson’s disease, leads to motor impairments like a shuffling gait when walking. The basal ganglia also regulate motivation. For example, when a wasp sting led to bilateral basal ganglia damage in a 25-year-old businessman, he began to spend all his days in bed and showed no interest in anything or anybody. But when he was externally stimulated—as when someone asked to play a card game with him—he was able to function normally. Interestingly, he and other similar patients do not report feeling bored or frustrated by their state.

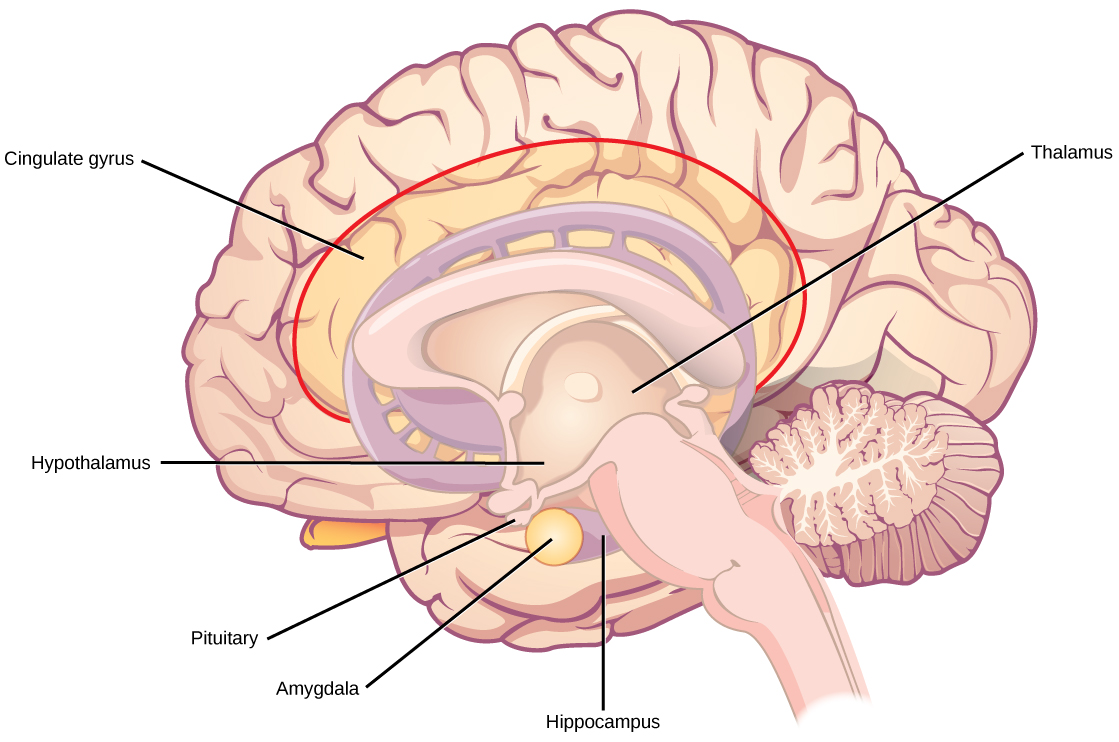

Thalamus

The thalamus (Greek for “inner chamber”), illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), acts as a gateway to and from the cortex. It receives sensory and motor inputs from the body and also receives feedback from the cortex. This feedback mechanism can modulate conscious awareness of sensory and motor inputs depending on the attention and arousal state of the animal. The thalamus helps regulate consciousness, arousal, and sleep states. A rare genetic disorder called fatal familial insomnia causes the degeneration of thalamic neurons and glia. This disorder prevents affected patients from being able to sleep, among other symptoms, and is eventually fatal.

Hypothalamus

Below the thalamus is the hypothalamus, shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). The hypothalamus controls the endocrine system by sending signals to the pituitary gland, a pea-sized endocrine gland that releases several different hormones that affect other glands as well as other cells. This relationship means that the hypothalamus regulates important behaviors that are controlled by these hormones. The hypothalamus is the body’s thermostat—it makes sure key functions like food and water intake, energy expenditure, and body temperature are kept at appropriate levels. Neurons within the hypothalamus also regulate circadian rhythms, sometimes called sleep cycles.

Limbic System

The limbic system is a connected set of structures that regulates emotion, as well as behaviors related to fear and motivation. It plays a role in memory formation and includes parts of the thalamus and hypothalamus as well as the hippocampus. One important structure within the limbic system is a temporal lobe structure called the amygdala (Greek for “almond”), illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). The two amygdala are important both for the sensation of fear and for recognizing fearful faces. The cingulate gyrus helps regulate emotions and pain.

Cerebellum

The cerebellum (Latin for “little brain”), shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), sits at the base of the brain on top of the brainstem. The cerebellum controls balance and aids in coordinating movement and learning new motor tasks.

Brainstem

The brainstem, illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), connects the rest of the brain with the spinal cord. It consists of the midbrain, medulla oblongata, and the pons. Motor and sensory neurons extend through the brainstem allowing for the relay of signals between the brain and spinal cord. Ascending neural pathways cross in this section of the brain allowing the left hemisphere of the cerebrum to control the right side of the body and vice versa. The brainstem coordinates motor control signals sent from the brain to the body. The brainstem controls several important functions of the body including alertness, arousal, breathing, blood pressure, digestion, heart rate, swallowing, walking, and sensory and motor information integration.

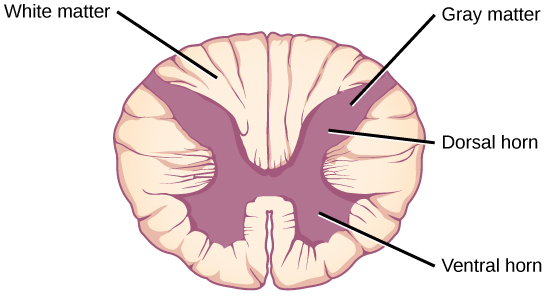

Spinal Cord

Connecting to the brainstem and extending down the body through the spinal column is the spinal cord, shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). The spinal cord is a thick bundle of nerve tissue that carries information about the body to the brain and from the brain to the body. The spinal cord is contained within the bones of the vertebrate column but is able to communicate signals to and from the body through its connections with spinal nerves (part of the peripheral nervous system). A cross-section of the spinal cord looks like a white oval containing a gray butterfly-shape, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\). Myelinated axons make up the “white matter” and neuron and glial cell bodies make up the “gray matter.” Gray matter is also composed of interneurons, which connect two neurons each located in different parts of the body. Axons and cell bodies in the dorsal (facing the back of the animal) spinal cord convey mostly sensory information from the body to the brain. Axons and cell bodies in the ventral (facing the front of the animal) spinal cord primarily transmit signals controlling movement from the brain to the body.

The spinal cord also controls motor reflexes. These reflexes are quick, unconscious movements—like automatically removing a hand from a hot object. Reflexes are so fast because they involve local synaptic connections. For example, the knee reflex that a doctor tests during a routine physical is controlled by a single synapse between a sensory neuron and a motor neuron. While a reflex may only require the involvement of one or two synapses, synapses with interneurons in the spinal column transmit information to the brain to convey what happened (the knee jerked, or the hand was hot).

In the United States, there around 10,000 spinal cord injuries each year. Because the spinal cord is the information superhighway connecting the brain with the body, damage to the spinal cord can lead to paralysis. The extent of the paralysis depends on the location of the injury along the spinal cord and whether the spinal cord was completely severed. For example, if the spinal cord is damaged at the level of the neck, it can cause paralysis from the neck down, whereas damage to the spinal column further down may limit paralysis to the legs. Spinal cord injuries are notoriously difficult to treat because spinal nerves do not regenerate, although ongoing research suggests that stem cell transplants may be able to act as a bridge to reconnect severed nerves. Researchers are also looking at ways to prevent the inflammation that worsens nerve damage after injury. One such treatment is to pump the body with cold saline to induce hypothermia. This cooling can prevent swelling and other processes that are thought to worsen spinal cord injuries.

Summary

The vertebrate central nervous system contains the brain and the spinal cord, which are covered and protected by three meninges. The brain contains structurally and functionally defined regions. In mammals, these include the cortex (which can be broken down into four primary functional lobes: frontal, temporal, occipital, and parietal), basal ganglia, thalamus, hypothalamus, limbic system, cerebellum, and brainstem—although structures in some of these designations overlap. While functions may be primarily localized to one structure in the brain, most complex functions, like language and sleep, involve neurons in multiple brain regions. The spinal cord is the information superhighway that connects the brain with the rest of the body through its connections with peripheral nerves. It transmits sensory and motor input and also controls motor reflexes.

Glossary

- amygdala

- structure within the limbic system that processes fear

- arachnoid mater

- spiderweb-like middle layer of the meninges that cover the central nervous system

- basal ganglia

- interconnected collections of cells in the brain that are involved in movement and motivation; also known as basal nuclei

- basal nuclei

- see basal ganglia

- brainstem

- portion of the brain that connects with the spinal cord; controls basic nervous system functions like breathing, heart rate, and swallowing

- cerebellum

- brain structure involved in posture, motor coordination, and learning new motor actions

- cerebral cortex

- outermost sheet of brain tissue; involved in many higher-order functions

- choroid plexus

- spongy tissue within ventricles that produces cerebrospinal fluid

- cingulate gyrus

- helps regulate emotions and pain; thought to directly drive the body’s conscious response to unpleasant experiences

- corpus callosum

- thick fiber bundle that connects the cerebral hemispheres

- cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

- clear liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord and fills the ventricles and central canal; acts as a shock absorber and circulates material throughout the brain and spinal cord.

- dura mater

- tough outermost layer that covers the central nervous system

- frontal lobe

- part of the cerebral cortex that contains the motor cortex and areas involved in planning, attention, and language

- gyrus

- (plural: gyri) ridged protrusions in the cortex

- hippocampus

- brain structure in the temporal lobe involved in processing memories

- hypothalamus

- brain structure that controls hormone release and body homeostasis

- limbic system

- connected brain areas that process emotion and motivation

- meninge

- membrane that covers and protects the central nervous system

- occipital lobe

- part of the cerebral cortex that contains visual cortex and processes visual stimuli

- parietal lobe

- part of the cerebral cortex involved in processing touch and the sense of the body in space

- pia mater

- thin membrane layer directly covering the brain and spinal cord

- proprioception

- sense about how parts of the body are oriented in space

- somatosensation

- sense of touch

- spinal cord

- thick fiber bundle that connects the brain with peripheral nerves; transmits sensory and motor information; contains neurons that control motor reflexes

- sulcus

- (plural: sulci) indents or “valleys” in the cortex

- temporal lobe

- part of the cerebral cortex that processes auditory input; parts of the temporal lobe are involved in speech, memory, and emotion processing

- thalamus

- brain area that relays sensory information to the cortex

- ventricle

- cavity within brain that contains cerebrospinal fluid