1.5: Ecuaciones de bucle y nodo

- Page ID

- 85446

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Hay dos formas formales bien desarrolladas de resolver los potenciales y corrientes en las redes, a menudo denominadas métodos de ecuación de bucle y nodo. Están estrechamente relacionados, utilizando KCL y KVL junto con restricciones de elementos para construir conjuntos de ecuaciones que luego pueden resolverse para potenciales y corrientes.

- En el método de ecuación de nodos, KCL se escribe en cada nodo de la red, con corrientes expresadas en términos de los potenciales de nodo. KVL está satisfecho porque los potenciales de nodo son únicos.

- En el método de ecuación de bucle, KVL se escribe sobre una colección de rutas cerradas en la red. Las “corrientes de bucle” se definen, y se hacen para satisfacer KCL, y los voltajes de rama se expresan en términos de ellos.

Los dos métodos son equivalentes y la elección entre ellos suele ser una cuestión de preferencia personal. El método de la ecuación de nodos es probablemente más utilizado, y se presta bien al análisis por computadora.

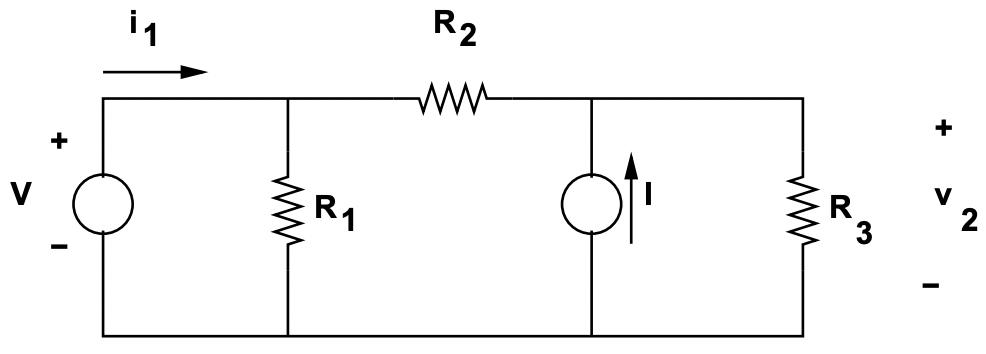

Para ilustrar cómo funcionan estos métodos, considere la red de la Figura 12.

Esta red cuenta con tres nodos. Vamos a escribir KCL para cada uno de los nodos, pero tenga en cuenta que solo se requieren dos ecuaciones explícitas. Si KCL se satisface en dos de los nodos, se satisface automáticamente en el tercero. Por lo general, el nodo de referencia es aquel para el que no escribimos la expresión.

Figura 12: Red de muestra

Figura 12: Red de muestraKCL escrito para los dos nodos superiores de la red es:

\[\ -i_{1}+\frac{V}{R_{1}}+\frac{V-v_{2}}{R_{2}}=0\label{9} \]

\[\ -I+\frac{v_{2}-V}{R_{2}}+\frac{v_{2}}{R_{3}}=0\label{10} \]

Estas dos expresiones se resuelven fácilmente para las dos incógnitas,\(\ i_{1}\) y\(\ v_{2}\):

\ (\\ begin {array} {c}

v_ {2} =\ frac {R_ {3}} {R_ {2} +R_ {3}} V+\ frac {R_ {2} R_ {3}} {R_ {2} +R_ {3}} I\\

i_ {1} =\ frac {R_ {1} +R_ {2} +R_ {3}} {R_ {1}\ izquierda (R_ {2} +R_ {3}\ derecha)} V-\ frac {R_ {3}} {R_ {2} +R_ {3}} I

\ fin {array}\)

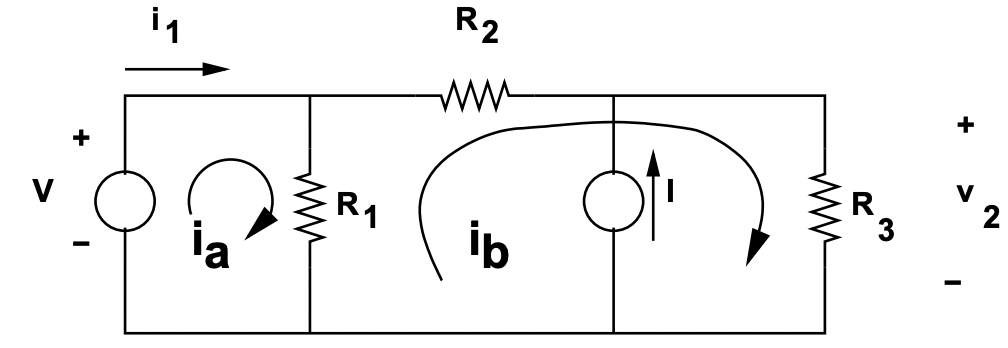

Figura 13: Red de muestra que muestra bucles

Figura 13: Red de muestra que muestra buclesEl método de la ecuación de bucle es similar. Necesitamos el mismo número de expresiones independientes (dos), así que necesitamos tomar dos bucles independientes. Para ello, tome como los bucles como se muestra en la Figura 13:

- El bucle que incluye la fuente de voltaje y\(\ R_{1}\).

- El bucle que incluye\(\ R_{1}, R_{2}\), y\(\ R_{3}\).

También es necesario definir corrientes de bucle, que denotaremos como\(\ i_{a}\) y\(\ i_{b}\). Estas son las corrientes que circulan alrededor de los dos bucles. Tenga en cuenta que donde los bucles se cruzan, la corriente de rama real será la suma o diferencia entre las corrientes de bucle. Para este ejemplo, supongamos que las corrientes de bucle están definidas para estar circulando en sentido antihorario en los dos bucles. Las dos ecuaciones de bucle son:

\[\ V+R_{1}\left(i_{a}-i_{b}\right)=0\label{11} \]

\[\ R_{1}\left(i_{b}-i_{a}\right)+R_{2} i_{b}+R_{3}\left(i_{b}-I\right)=0\label{12} \]

Estos son igualmente fáciles de resolver para las dos incógnitas, en este caso las dos corrientes de bucle\(\ i_{a}\) y\(\ i_{b}\).