1.8: Redes de dos puertos

- Page ID

- 85454

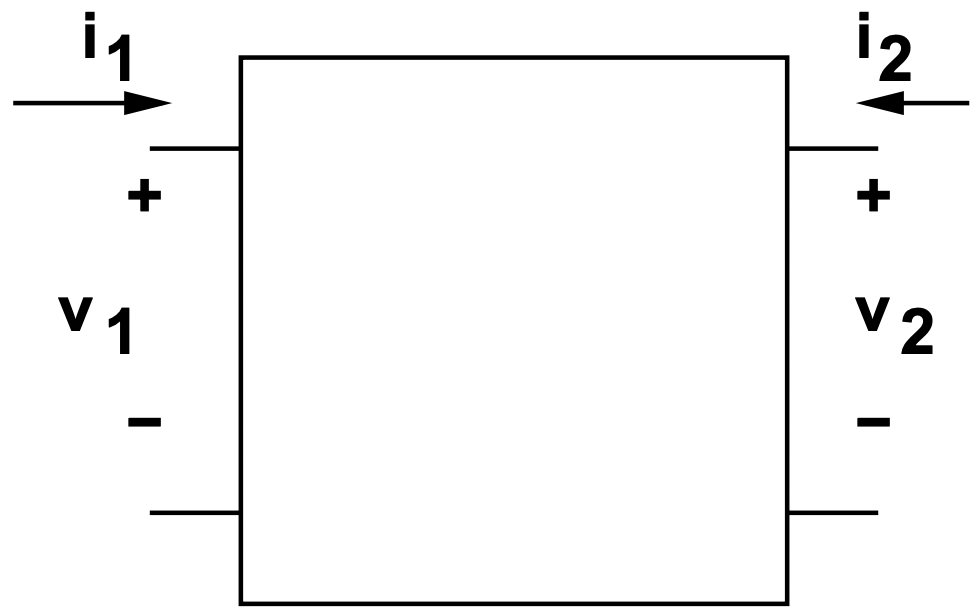

Hasta el momento, hemos tratado con una serie de redes que se puede decir que son circuitos de un puerto o de par de terminales únicos. Es decir, la acción importante ocurre en un solo par de terminales, y se caracteriza por una impedancia y por una tensión de circuito abierto o una corriente de cortocircuito, formando así un circuito equivalente a Thevenin o Norton. Un segundo, y para nosotros muy importante, la clase de red eléctrica cuenta con dos (o a veces más) pares de terminales. Consideraremos formalmente aquí la red de dos puertos, ilustrada esquemáticamente en la Figura 21.

Hay una serie de formas de caracterizar este tipo de redes. Por el momento, considera que es pasivo, de manera que no hay salida sin alguna entrada y no hay fuentes dependientes.

Figura 21: Red de dos puertos

Figura 21: Red de dos puertosEntonces podemos caracterizar la red en términos de las corrientes en sus terminales en términos de los voltajes, o, a la inversa, podemos describir los voltajes en términos de las corrientes en los terminales. Se dice que estas dos formas de describir la red son los parámetros de admitancia o impedancia. Estos podrán ser escritos de la siguiente manera:

El punto de vista del parámetro de impedancia produciría, para una red resistiva, la siguiente relación entre tensiones y corrientes:

\ [\\ left [\ begin {array} {c}

v_ {1}\\

v_ {2}

\ end {array}\ right] =\ left [\ begin {array} {cc}

R_ {11} & R_ {12}\\

R_ {21} & R_ {22}

\ end {array}\ right]\ left [\ begin {array} {c}

i_ {1}\\

i_ {2}\ etiqueta {14}

\ end {array}\ derecha]\ nonumber\]

Del mismo modo, el punto de vista del parámetro de admisión produciría una relación similar:

\ [\\ left [\ begin {array} {c}

i_ {1}\\

i_ {2}

\ end {array}\ right] =\ left [\ begin {array} {ll}

G_ {11} & G_ {12}\\

G_ {21} & G_ {22}

\ end {array}\ right]\ left [\ begin {array} {l}

v_ {1}\\

v_ {2}\ etiqueta {15}

\ end {array}\ derecha]\ nonumber\]

Estas dos relaciones son, por supuesto, las inversas la una de la otra. Es decir:

\ [\\ left [\ begin {array} {ll}

G_ {11} & G_ {12}\\

G_ {21} & G_ {22}

\ end {array}\ right] =\ left [\ begin {array} {cc}

R_ {11} & R_ {12}\\

R_ {21} & R_ {22}

\ end {array}\ right] ^ {-1}\ label {16}\]

Si las redes son lineales y pasivas (es decir, no hay fuentes dependientes en su interior), también exhiben la propiedad de reciprocidad. En una red recíproca, la impedancia de transferencia o la admitancia de transferencia es la misma en ambas direcciones. Es decir:

\ (\\ begin {array} {l}

R_ {12} =R_ {21}\\

G_ {12} =G_ {21}

\ end {array}\ label {17}\)

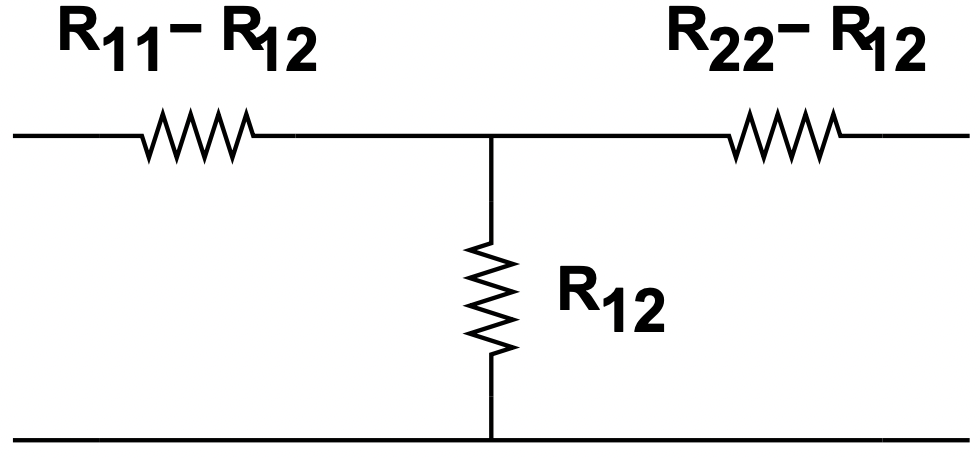

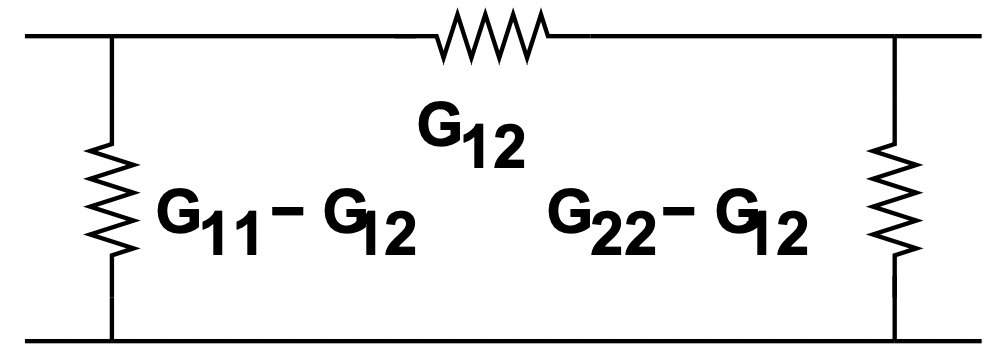

A menudo es útil expresar redes de dos puertos en términos de redes T o Π, mostradas en las figuras 22 y 23.

En ocasiones es útil poner en cascada redes de dos puertos, como se muestra en la Figura 24. La combinación resultante es en sí misma un puerto de dos. Supongamos que tenemos un par de redes caracterizadas por parámetros de impedancia:

\ (\\ left [\ begin {array} {c}

v_ {1}\\

v_ {2}

\ end {array}\ right] =\ left [\ begin {array} {cc}

R_ {11} & R_ {12}\\

R_ {12} & R_ {22}

\ end {array}\ right]\ left [\ begin {array} {c}

i_ {1}\\

i_ {2}

\ end {array}\ derecha]\)

Figura 22: T- Red Equivalente

Figura 22: T- Red Equivalente Figura 23: Red equivalente a p

Figura 23: Red equivalente a p\ (\\ left [\ begin {array} {l}

v_ {3}\\

v_ {4}

\ end {array}\ right] =\ left [\ begin {array} {ll}

R_ {33} & R_ {34}\\

R_ {34} & R_ {44}\ end {array}

\ end {array}\ derecha]\ left [\ begin {array} {c}

i_ {3}\\

i_ {4}

\ end {array}\ derecha]\)

Al señalar eso\(\ v_{2}=v_{3}\) y\(\ i_{3}=-i_{2}\), es posible demostrar, con un poco de manipulación, que:

\ (\\ left [\ begin {array} {c}

v_ {1}\\

v_ {4}

\ end {array}\ right] =\ left [\ begin {array} {ll}

R_ {11} ^ {\ prime} & R_ {14}\\

R_ {14} & R_ {44} ^ {\ prime}

\ end {array}\ derecha]\ izquierda [\ begin matriz} {c}

i_ {1}\\

i_ {4}

\ end {array}\ derecha]\)

donde

\ (\\ begin {array} {c}

R_ {11} ^ {\ prime} =R_ {11} -\ frac {R_ {12} ^ {2}} {R_ {22} +R_ {33}}\\

R_ {44} ^ {\ prime} =R_ {44} -\ frac {R_ {34} ^ {2}} {R_ {22} +R_ {33}}\\

R_ {14} =\ frac {R_ {12} R_ {34}} {R_ {22} +R_ {33}}

\ final {matriz}\)