7.3: Serie Discreta Común de Fourier

- Page ID

- 86509

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introducción

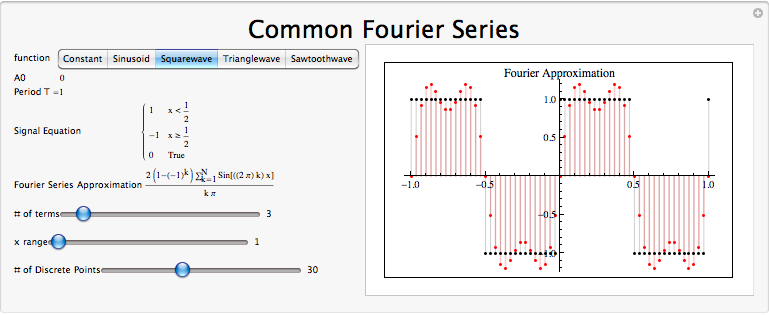

Una vez que se ha obtenido una comprensión sólida de los fundamentos del análisis de series de Fourier y la Derivación General de los Coeficientes de Fourier, es útil tener una comprensión de las señales comunes utilizadas en la Aproximación de Señales de la Serie de Fourier.

Derivando los Coeficientes

Considera una onda cuadrada\(f(x)\) de longitud 1. En el rango [0,1), esto se puede escribir como

\ [x (t) =\ left\ {\ begin {array} {rl}

1 & t\ leq\ frac {1} {2}\\

-1 & t>\ frac {1} {2}

\ end {array}\ right. \ nonumber\]

Real Even Signals Dado que la onda cuadrada es una señal real y uniforme,

- \(f(t)=f(−t)\)INCLUSO

- \(f(t)=f^*(t)\)REAL

por lo tanto,

- \(c_n=c_{−n}\)INCLUSO

- \(c_n=c_n^*\)REAL

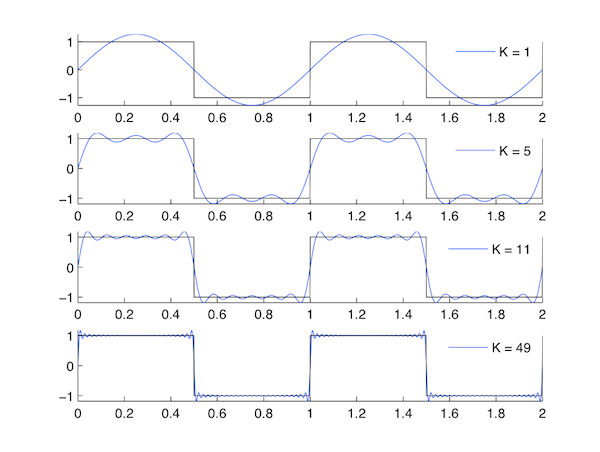

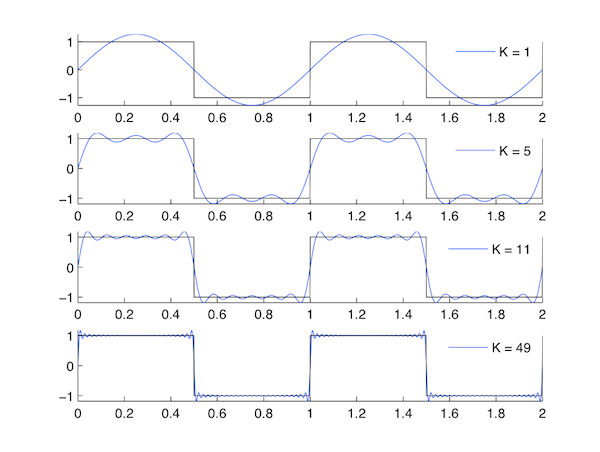

Derivación de los Coeficientes para otras señales

La onda cuadrada es el ejemplo estándar, pero otras señales importantes también son útiles para analizar, y estas se incluyen aquí.

Forma de onda constante

Esta señal es relativamente autoexplicativa: se saca la porción variable en el tiempo del Coeficiente de Fourier, y nos quedamos simplemente con una función constante en todo el tiempo.

\[x(t)=1 \nonumber \]

Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\)

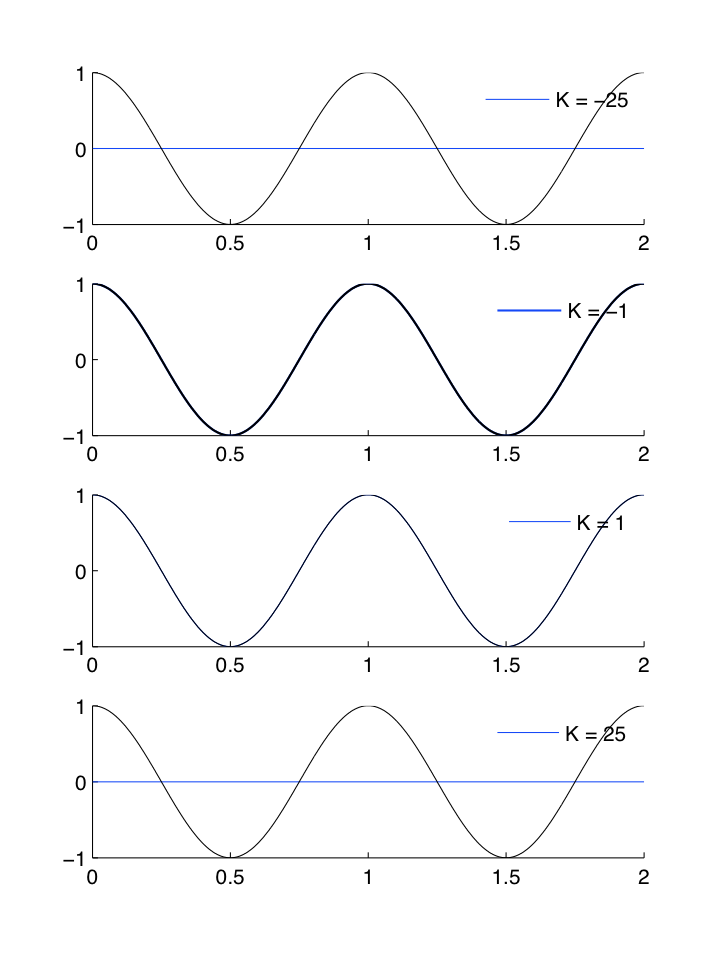

Forma de onda sinusoidal

Con esta señal, solo se elige una frecuencia específica de Coeficiente variable en el tiempo (dado que la ecuación de la Serie de Fourier incluye una onda sinusoidal, esto es intuitivo), y todas las demás se filtran, y este único coeficiente variable en el tiempo coincidirá exactamente con la señal deseada.

\[x(t)=\cos (2 \pi t) \nonumber \]

Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\)

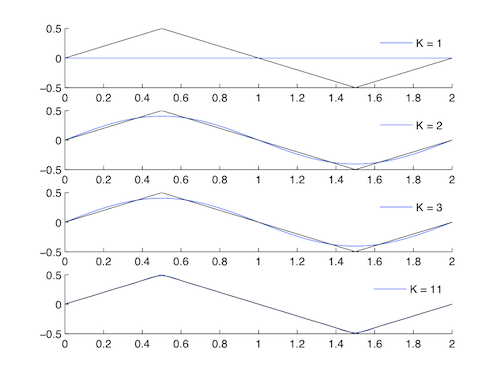

Forma de onda triangular

\ [x (t) =\ left\ {\ begin {array} {rl}

t & t\ leq 1/2\\

1-t & t>1/2

\ end {array}\ right. \ nonumber\]

Esta es una forma más compleja de aproximación de señal a la onda cuadrada. Debido a las Propiedades de Simetría de la Serie de Fourier, la onda triangular es una señal real e impar, a diferencia de la señal de onda cuadrada real y par. Esto significa que

- \(f(t)=−f(−t)\)ODD

- \(f(t)=f^*(t)\)REAL

por lo tanto,

- \(c_n=−c_{−n}\)

- \(c_n=−c_n^*\)Imaginario

Figura\(\PageIndex{4}\)

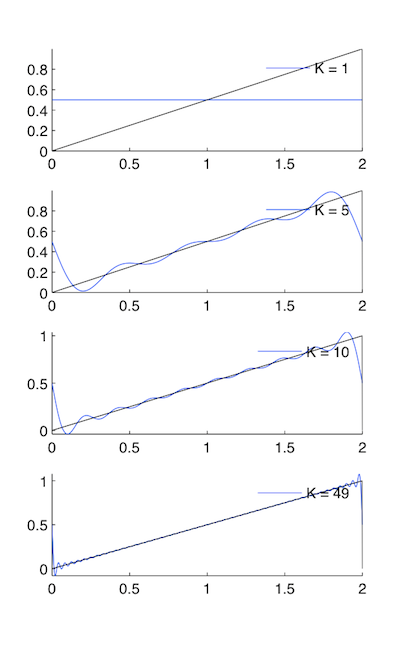

Forma de onda de diente de

\[x(t) = t/2 \nonumber \]

Debido a las propiedades de simetría de la serie de Fourier, la onda en diente de sierra se puede definir como una señal real e impar, a diferencia de la señal de onda cuadrada real y par. Esto tiene implicaciones importantes para los Coeficientes de Fourier.

Figura\(\PageIndex{5}\)

Conclusión

En resumen, existe una gran variedad entre las Transformadas de Fourier comunes. Aquí se proporciona una tabla resumida con la información esencial.

| Descripción | Señal de dominio de tiempo para\(n \in \mathbb{Z}[0, N-1]\) | Señal de dominio de frecuencia\(k \in \mathbb{Z}[0, N-1]\) |

| Función Constante | 1 | \(\delta(k)\) |

| Impulso de Unidad | \(\delta(n)\) | \(\frac{1}{N}\) |

| Exponencial Complejo | \(e^{j 2 \pi m n / N}\) | \(\delta\left((k-m)_{N}\right)\) |

| Forma de onda sinusoidal | \(\cos (j 2 \pi m n / N)\) | \(\frac{1}{2}\left(\delta\left((k-m)_{N}\right)+\delta\left((k+m)_{N}\right)\right)\) |

| Forma de onda de caja\((M < N/2)\) | \(\delta(n)+\sum_{m=1}^{M} \delta\left((n-m)_{N}\right)+\delta\left((n+m)_{N}\right)\) | \(\frac{\sin ((2 M+1) k \pi / N)}{N \sin (k \pi / N)}\) |

| Forma de onda Dsinc\((M<N/2)\) | \(\frac{\sin ((2 M+1) n \pi / N)}{\sin (n \pi / N)}\) | \(\delta(k)+\sum_{m=1}^{M} \delta\left((k-m)_{N}\right)+\delta((k+m)_N)\) |