6.7: Funciones compuestas

- Page ID

- 112984

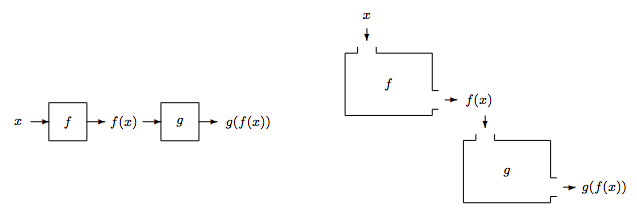

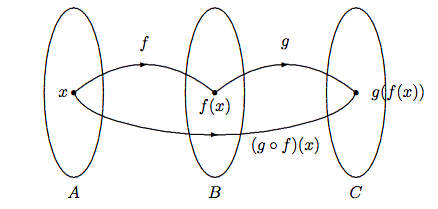

Dadas funciones\(f :{A}\to{B}\) y\(g :{B}\to{C}\), la función compuesta,\(g\circ f\), que se pronuncia como “\(g\)círculo\(f\)”, se define como\[{g\circ f}:{A}\to{C}, \qquad (g\circ f)(x) = g(f(x)). \nonumber\] La imagen se obtiene en dos pasos. En primer lugar,\(f(x)\) se obtiene. A continuación, se pasa a\(g\) para obtener el resultado final. Funciona como conectar dos máquinas para formar una más grande, ver Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\). También podemos usar un diagrama de flechas para proporcionar otra vista pictórica, ver Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\).

El valor numérico de se\((g\circ f)(x)\) puede calcular en dos pasos. Por ejemplo, para calcular\((g\circ f)(5)\), primero calculamos el valor de\(f(5)\), y luego el valor de\(g(f(5))\). Para encontrar la descripción algebraica de\((g\circ f)(x)\), necesitamos calcular y simplificar la fórmula para\(g(f(x))\). En este caso, muchas veces es más fácil comenzar desde la función “exterior”. Más precisamente, comenzar con\(g\), y escribir la respuesta intermedia en términos de\(f(x)\), luego sustituir en la definición de\(f(x)\) y simplificar el resultado.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{1}\label{eg:compfcn-01}\)

Supongamos\(f,g :{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) que se definen como\(f(x)=x^2\), y\(g(x)=3x+1\). ENCONTRAMOS

\[\displaylines{ (g\circ f)(x)=g(f(x))=3[f(x)]+1=3x^2+1, \cr (f\circ g)(x)=f(g(x))=[g(x)]^2=(3x+1)^2. \cr} \nonumber\]

Por lo tanto,

\[g \circ f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}, \qquad (g \circ f)(x)=3x^2+1 \nonumber\]

\[f \circ g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}, \qquad (f \circ g)(x)=(3x+1)^2 \nonumber\]

Observamos que, en general,\(f\circ g \neq g\circ f\).

ejercicio práctico\(\PageIndex{1}\label{he:compfcn-01}\)

Si\(p,q:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) se definen como\(p(x)=2x+5\), y\(q(x)=x^2+1\), determinar\(p\circ q\) y\(q\circ p\). No olvides describir el dominio y el codominio.

ejercicio práctico\(\PageIndex{2}\label{he:compfcn-02}\)

Las funciones\(f,g :\mathbb{Z}_{12} \to \mathbb{Z}_{12}\) están definidas por

\[f(x) \equiv 7x+2 \pmod{12}, \qquad\mbox{and}\qquad g(x) \equiv 5x-3 \pmod{12}. \nonumber\]

Calentar la función compuesta\(f\circ g\).

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{2}\label{eg:compfcn-02}\)

Definir\(f,g :{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) como

\[f(x) = \cases{ 3x+1 & if $x < 0$, \cr 2x+5 & if $x\geq0$, \cr} \nonumber\]

y\(g(x)=5x-7\). Encuentra\(g\circ f\).

- Contestar

-

Dado que\(f\) es una función definida por partes, esperamos que la función compuesta también\(g\circ f\) sea una función definida por partes. Se define por\[(g\circ f)(x) = g(f(x)) = 5f(x)-7 = \cases{ 5(3x+1)-7 & if $x < 0$, \cr 5(2x+5)-7 & if $x\geq0$. \cr} \nonumber\]

Después de la simplificación, encontramos\(g \circ f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\), por:\[(g\circ f)(x) = \cases{ 15x-2 & if $x < 0$, \cr 10x+18 & if $x\geq0$. \cr} \nonumber\] En este ejemplo, es bastante obvio cuáles son el dominio y el codominio. Sin embargo, siempre es una buena práctica incluirlos cuando describimos una función.

ejercicio práctico\(\PageIndex{3}\label{he:compfcn-03}\)

Las funciones\(f :{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) y\(g :{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) son definidas por\[f(x) = 3x+2, \qquad\mbox{and}\qquad g(x) = \cases{ x^2 & if $x\leq5$, \cr 2x-1 & if $x > 5$. \cr} \nonumber\] Determinar\(f\circ g\).

El siguiente ejemplo ilustra además por qué a menudo es más fácil comenzar con la función externa\(g\) en la derivación de la fórmula para\(g(f(x))\).

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{3}\label{eg:compfcn-03}\)

La función\(p :{[1,5]}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) está definida por

\[p(x) = \cases{ 2x+3 & if $1\leq x< 3$, \cr 5x-2 & if $3\leq x\leq 5$; \cr} \nonumber\]

y la función\(q :{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) por

\[q(x) = \cases{ 4x & if $x < 7$, \cr 3x & if $x\geq7$. \cr} \nonumber\]

Describir la función\(q\circ p\).

- Contestar

-

Ya que\[(q\circ p)(x) = q(p(x)) = \cases{ 4p(x) & if $p(x)<7$, \cr 3p(x) & if $p(x)\geq7$, \cr} \nonumber\] tenemos que averiguar cuándo será\(p(x)<7\), y cuándo lo hará\(p(x)\geq7\), porque estas condiciones determinan lo que debemos hacer a continuación para continuar con el cómputo. Ya que\(p(x)\) se calcula de dos maneras diferentes, tenemos que analizar dos casos.

Caso 1:\(1\leq x<3\). En este caso,\(p(x)\) se define como\(2x+3\). Esta es una función creciente, de ahí,\[p(x)\geq p(1) = 2\cdot1+3 = 5, \qquad\mbox{and}\qquad p(x) < p(3) = 2\cdot3+3 = 9. \nonumber\] para algunos\(x\) s en este rango, tenemos\(p(x)<7\), pero para otros\(x\) -valores, tenemos\(p(x)\geq7\). Necesitamos conocer el punto de corte. Esto sucede cuando\(p(x)=2x+3=7\), es decir, cuando\(x=2\). Esto lleva a dos subcasos.

- Caso 1a: Cuando\(1\leq x<2\), tenemos\(p(x)=2x+3 <7\). Por lo tanto,\[q(p(x)) = 4p(x) = 4(2x+3) = 8x+12. \nonumber\]

- Caso 1b: Cuando\(2\leq x<3\), tenemos\(p(x)=2x+3\geq7\). Por lo tanto,\[q(p(x)) = 3p(x) = 3(2x+3) = 6x+9. \nonumber\]

Caso 2:\(3\leq x\leq 5\). En este caso,\(p(x)\) se calcula como\(5x-2\). Esta es una función creciente, de ahí\(p(x) \geq p(3) = 5\cdot3-2=13\). Ya que siempre\(p(x)\) es mayor que 7, encontramos\[q(p(x)) = 3p(x) = 3(5x-2) = 15x-6. \nonumber\]

Combinando estos casos, determinamos que la función compuesta\({q\circ p\,}{[1,5]}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) está definida por\[(q\circ p)(x) = \cases{ 8x+12 & if $1\leq x<2$, \cr 6x+9 & if $2\leq x<3$, \cr 15x-6 & if $3\leq x\leq5$. \cr} \nonumber\] Estudia este ejemplo nuevamente para asegurarnos de que la entiendas a fondo.

ejercicio práctico\(\PageIndex{4}\label{he:compfcn-04}\)

Las funciones\(f,g :{\mathbb{Z}}\to{\mathbb{Z}}\) son definidas por\[f(n) = \cases{ n+1 & if $n$ is even \cr n-1 & if $n$ is odd \cr} \qquad g(n) = \cases{ n+3 & if $n$ is even \cr n-7 & if $n$ is odd \cr} \nonumber\] Determinar\(f\circ g\).

Estrictamente hablando,\(g\circ f\) está bien definido si el codominio de\(f\) iguales al dominio de\(g\). Es claro que todavía\(g\circ f\) está bien definido si\(\mathrm{ im }{f}\) es un subconjunto del dominio de\(g\). De ahí, si\[f :{A}{B}, \quad g :{C}{D}, \nonumber\] entonces\(g\circ f\) está bien definido si\(B\subseteq C\), o más generalmente,\(\mathrm{ im }{f}\subseteq C\).

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{4}\label{eg:compfcn-04}\)

Vamos a\(\mathbb{R}^*\) denotar el conjunto de números reales distintos de cero. Supongamos

\[f : \mathbb{R}^* \to \mathbb{R}, \qquad f(x)=\frac{1}{x} \nonumber\]

\[g : \mathbb{R} \to (0, \infty), \qquad g(x)=3x^2+11. \nonumber\]

Determinar\(f\circ g\) y\(g\circ f\). Asegúrese de especificar sus dominios y codominios.

- Contestar

-

Para computar\(f\circ g\), empezamos con\(g\), cuyo dominio es\(\mathbb{R}\). De ahí,\(\mathbb{R}\) es el dominio de\(f\circ g\). El resultado de\(g\) es un número en\((0,\infty)\). El intervalo\((0,\infty)\) contiene solo números positivos, por lo que es un subconjunto de\(\mathbb{R}^*\). Por lo tanto, podemos continuar nuestro cómputo con\(f\), y el resultado final es un número en\(\mathbb{R}\). De ahí que el codominio de\(f\circ g\) es\(\mathbb{R}\). La imagen se calcula de acuerdo a\(f(g(x)) = 1/g(x) = 1/(3x^2+11)\). Ahora estamos listos para presentar nuestra respuesta:

\(f \circ g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R},\)por:

\[(f \circ g)(x) = \frac{1}{3x^2+11}. \nonumber\]

De manera similar, la función compuesta\(g\circ f :{\mathbb{R}^*} {(0,\infty)}\) se define como\[(g\circ f)(x) = \frac{3}{x^2}+11. \nonumber\] Asegúrese de entender cómo determinamos el dominio y el codominio de\(g\circ f\).

ejercicio práctico\(\PageIndex{5}\label{he:compfcn-05}\)

Dejar\(\mathbb{Z}\) denotar el conjunto de enteros. Determinar\(h\circ g\), ¿dónde\[\begin{array}{cc} g: \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{R}, & g(x) = \sqrt{|x|}, \\ h: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}, & h(x) = (x-5)^2 \end{array} \nonumber\] está\(g\circ h\) bien definido? ¡Explique!

Como es habitual, tenga especial precaución con la aritmética modular.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{5}\label{eg:compfcn-05}\)

Definir\(f :{\mathbb{Z}_{15}}\to{\mathbb{Z}_{23}}\) y\(g :{\mathbb{Z}_{23}}\to{\mathbb{Z}_{32}}\) según

\[\begin{aligned} f(x) &\equiv& 3x+5 \pmod{23}, \\ g(x) &\equiv& 2x+1 \pmod{32}. \end{aligned} \nonumber\]

Podemos esperar que\(g\circ f :{\mathbb{Z}_{15}}\to{\mathbb{Z}_{23}}\) se definan como

\[(g\circ f)(x) \equiv 2(3x+5)+1 \equiv 6x+11) \pmod{32}. \nonumber\]

En particular,\((g\circ f)(8) \equiv 59 \equiv 27\) (mod 32).

Si realizamos el cálculo paso a paso, nos encontramos con\(f(8)\equiv 29\equiv6\) (mod 23), del\[(g\circ f)(8) = g(f(8)) = g(6) \equiv 13 \pmod{32}. \nonumber\] cual obtenemos que no es lo que acabamos de encontrar. ¿Puedes explicar por qué?

- Contestar

-

La fuente del problema son los diferentes módulos utilizados en\(f\) y\(g\). La función compuesta debe definirse como\[(g\circ f)(x) \equiv 2r+1 \pmod{32}, \qquad\mbox{where } r \equiv 3x+5 \pmod{23}. \nonumber\] De alguna manera, esta definición nos obliga a llevar a cabo el cómputo en dos pasos. En consecuencia, obtendremos la respuesta correcta\((g\circ f)(8)=13\).

Existe una estrecha conexión entre una biyección y su función inversa, desde la perspectiva de la composición.

Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\label{thm:compfcn-inv}\)

Para una función biyectiva\(f :{A}\to{B}\),

\[f^{-1}\circ f=i_A, \qquad\mbox{and}\qquad f\circ f^{-1}=i_B, \nonumber\]

donde\(i_A\) y\(i_B\) denotan la función de identidad en\(A\) y\(B\), respectivamente.

- Prueba

-

Para probarlo\(f^{-1}\circ f = i_A\), necesitamos demostrarlo\((f^{-1}\circ f)(a)=a\) para todos\(a\in A\). Asumir\(f(a)=b\). Entonces, porque\(f^{-1}\) es la función inversa de\(f\), eso lo sabemos\(f^{-1}(b)=a\). Por lo tanto,

\[(f^{-1}\circ f)(a) = f^{-1}(f(a)) = f^{-1}(b) = a, \nonumber\]

que es lo que queremos mostrar. La prueba de\(f\circ f^{-1} = i_B\) procceda exactamente de la misma manera, y se omite aquí.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{6}\label{eg:compfcn-06}\)

Mostrar que las funciones\(f,g :{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) definidas por\(f(x)=2x+1\) y\(g(x)=\frac{1}{2}(x-1)\) son funciones inversas entre sí.

- Contestar

-

El problema no le pide encontrar la función inversa de\(f\) o la función inversa de\(g\). En cambio, ya se te dan las respuestas. Tu trabajo es verificar que las respuestas sean efectivamente correctas, que las funciones sean funciones inversas entre sí.

Formar las dos funciones compuestas\(f\circ g\) y\(g\circ f\), y verificar si ambas son iguales a la función de identidad:

\[\displaylines{ \textstyle (f\circ g)(x) = f(g(x)) = 2 g(x)+1 = 2\left[\frac{1}{2}(x-1)\right]+1 = x, \cr \textstyle (g\circ f)(x) = g(f(x)) = \frac{1}{2} \big[f(x)-1\big] = \frac{1}{2} \left[(2x+1)-1\right] = x. \cr} \nonumber\]

Concluimos que\(f\) y\(g\) son funciones inversas entre sí.

ejercicio práctico\(\PageIndex{6}\label{he:compfcn-06}\)

Verificar que\(f :{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}^+}\) definidas por\(f(x)=e^x\), y\(g :{\mathbb{R}^+}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) definidas por\(g(x)=\ln x\), son funciones inversas entre sí.

Teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\label{thm:compfcn-02}\)

Supongamos\(f :{A}\to{B}\) y\(g :{B}\to{C}\). Dejar\(i_A\) y\(i_B\) denotar la función de identidad en\(A\) y\(B\), respectivamente. Tenemos los siguientes resultados.

- \(f\circ i_A=f\)y\(i_B\circ f=f\).

- Si ambos\(f\) y\(g\) son uno a uno, entonces también\(g\circ f\) es uno a uno.

- Si ambos\(f\) y\(g\) están en, entonces también\(g\circ f\) está en.

- Si ambos\(f\) y\(g\) son biyectivos, entonces también\(g\circ f\) es biyectiva. De hecho,\((g\circ f)^{-1}= f^{-1}\circ g^{-1}\).

- Prueba de (a)

-

Para\(f\circ i_A=f\) demostrarlo, necesitamos demostrarlo\((f\circ i_A)(a)= f(a)\) para todos\(a\in A\). Esto se desprende de la computación directa:\[(f\circ i_A)(a) = f(i_A(a)) = f(a). \nonumber\] Las pruebas de\(i_B\circ f=f\) y (b) — (d) se dejan como ejercicios.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{7}\label{eg:compfcn-07}\)

Los conversos de (b) y (c) en el Teorema 6.7.2 son falsos, como se demuestra en las funciones

\[\begin{array}{cc} g: \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}, & f(x)=2x, \\ h: \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}, & g(x)= \lfloor x/2 \rfloor \end{array} \nonumber\]

Aquí,\(g\circ f=i_{\mathbb{Z}}\), también lo\(g\circ f\) es uno a uno, y es obvio que también\(f\) es uno a uno, pero no\(g\) es uno a uno. Es fácil ver que ambos\(g\) y\(g\circ f\) están en marcha, pero no\(f\) lo es.

Resumen y revisión

- La composición de dos funciones\(f :{A}\to{B}\) y\(g :{B}\to{C}\) es la función\(g\circ f :{A}\to{C}\) definida por\((g\circ f)(x)=g(f(x))\).

- Si\(f :{A}\to{B}\) es biyectiva, entonces\(f^{-1}\circ f=i_A\) y\(f\circ f^{-1}=i_B\).

- Para verificar si\(f :{A}\to{B}\) y\(g :{B}\to{A}\) son inversos entre sí, necesitamos demostrar que

- \((g\circ f)(x)=g(f(x))=x\)para todos\(x\in A\), y

- \((f\circ g)(y)=f(g(y))=y\)para todos\(y\in B\).

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{1}\label{ex:compfcn-01}\)

Las funciones\(g,f:{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) están definidas por\(f(x)=5x-1\) y\(g(x)=3x^2+4\). Determinar\(f\circ g\) y\(g\circ f\).

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{2}\label{ex:compfcn-02}\)

La función\(h :{(0,\infty)}\to{(0,\infty)}\) está definida por\(h(x)=x+\frac{1}{x}\). Determinar\(h\circ h\). Simplifica tu respuesta tanto como sea posible.

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{3}\label{ex:compfcn-03}\)

Las funciones\(g,f :{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) están definidas por\(f(x)=1-3x\) y\(g(x)=x^2+1\). Evaluar\(f(g(f(0)))\).

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{4}\label{ex:compfcn-04}\)

Las funciones\(p :{(2,8]}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) y\(q :{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) son definidas por\[\begin{array}{rcl} p(x) &=& \cases{ 3x-1 & if $2<x\leq 4$, \cr 17-2x & if $4<x\leq 8$, \cr} \\ q(x) &=& \cases{ 4x-1 & if $x < 3$, \cr 3x+1 & if $x\geq3$. \cr} \end{array} \nonumber\] Evaluar\(q\circ p\).

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{5}\label{ex:compfcn-05}\)

Describir\(g\circ f\).

- \(f :{\mathbb{Z}}\to{\mathbb{N}}\),\(f(n)=n^2+1\);\(g :{\mathbb{N}}\to{\mathbb{Q}}\),\(g(n)=\frac{1}{n}\).

- \(f :{\mathbb{R}}\to{(0,1)}\),\(f(x)=1/(x^2+1)\);\(g :{(0,1)}\to{(0,1)}\),\(g(x)=1-x\).

- \(f :{\mathbb{Q}-\{2\}}\to{\mathbb{Q}^*}\),\(f(x)=1/(x-2)\);\(g :{\mathbb{Q}^*}\to{\mathbb{Q}^*}\),\(g(x)=1/x\).

- \(f :{\mathbb{R}}\to{[\,1,\infty)}\),\(f(x)=x^2+1\);\(g :{[\,1,\infty)}\to {[\,0,\infty)}\)\(g(x)=\sqrt{x-1}\).

- \(f :{\mathbb{Q}-\{10/3\}}\to{\mathbb{Q}-\{3\}}\),\(f(x)=3x-7\);\(g :{\mathbb{Q}-\{3\}}\to{\mathbb{Q}-\{2\}}\),\(g(x)=2x/(x-3)\).

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{6}\label{ex:compfcn-06}\)

Describir\(g\circ f\).

- \(f :{\mathbb{Z}}\to{\mathbb{Z}_5}\),\(f(n)\equiv n\) (mod 5);\(g :{\mathbb{Z}_5}\to{\mathbb{Z}_5}\),\(g(n)\equiv n+1\) (mod 5).

- \(f :{\mathbb{Z}_8}\to{\mathbb{Z}_{12}}\),\(f(n)\equiv 3n\) (mod 12);\(g :\to{\mathbb{Z}_{12}}{\mathbb{Z}_6}\),\(g(n)\equiv 2n\) (mod 6).

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{7}\label{ex:compfcn-07}\)

Describir\(g\circ f\).

- \(f :{\{1,2,3,4,5\}}\to{\{1,2,3,4,5\}}\),\(f(1)=5\)\(f(2)=3\),\(f(3)=2\),\(f(4)=1\),\(f(5)=4\);

- \(g :{\{1,2,3,4,5\}}\to{\{1,2,3,4,5\}}\);\(g(1)=3\),\(g(2)=1\),\(g(3)=5\),\(g(4)=4\),\(g(5)=2\)

- \(f :{\{a,b,c,d,e\}}\to{\{1,2,3,4,5\}}\);\(f(a)=5\),\(f(b)=1\),\(f(c)=2\),\(f(d)=4\),\(f(e)=3\);

- \(g :{\{1,2,3,4,5\}}\to{\{a,b,c,d,e\}}\);\(g(1)=e\),\(g(2)=d\),\(g(3)=a\),\(g(4)=c\),\(g(5)=b\)

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{8}\label{ex:compfcn-08}\)

Verificar que los\(f,g:{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) definidos por\[f(x) = \cases{ 11-2x & if $x<4$ \cr 15-3x & if $x\geq4$ \cr} \qquad\mbox{and}\qquad g(x) = \cases{ \textstyle \frac{1}{3}(15-x) & if $x\leq3$ \cr \textstyle \frac{1}{2}(11-x) & if $x > 3$ \cr} \nonumber\] son inversos entre sí.

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{9}\label{ex:compfcn-09}\)

Las funciones\(f,g :{\mathbb{Z}}\to{\mathbb{Z}}\) son definidas por\[f(n) = \cases{ 2n-1 & if $n\geq0$ \cr 2n & if $n < 0$ \cr} \qquad\mbox{and}\qquad g(n) = \cases{ n+1 & if $n$ is even \cr 3n & if $n$ is odd \cr} \nonumber\] Determinar\(g\circ f\).

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{10}\label{ex:compfcn-10}\)

Define las funciones\(f\) y\(g\) sobre su árbol genealógico materno (ver Problema 6.7.8 en Ejercicios 1.2) de acuerdo con\[\begin{array}{rcl} f(x) &=& \mbox{the mother of $x$}, \\ g(x) &=& \mbox{the eldest daughter of the mother of $x$}. \end{array} \nonumber\] Describa estas funciones.

- \(f\circ g\)

- \(g\circ f\)

- \(f\circ f\)

- \(g\circ g\)

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{11}\label{ex:compfcn-11}\)

Dadas las bijecciones\(f\) y\(g\), encontrar\(f\circ g\),\((f\circ g)^{-1}\) y\(g^{-1}\circ f^{-1}\).

- \(f :{\mathbb{Z}}\to{\mathbb{Z}}\),\(f(n)=n+1\);\(g :{\mathbb{Z}}\to{\mathbb{Z}}\),\(g(n)=2-n\).

- \(f :{\mathbb{Q}}\to{\mathbb{Q}}\),\(f(x)=5x\);\(g :{\mathbb{Q}}\to{\mathbb{Q}}\),\(g(x)=\frac{x-2}{5}\).

- \(f :{\mathbb{Q}-\{2\}}\to{\mathbb{Q}-\{2\}}\),\(f(x)=3x-4\);\(g :{\mathbb{Q}-\{2\}}\to{\mathbb{Q}-\{2\}}\),\(g(x)=\frac{x}{x-2}\).

- \(f :{\mathbb{Z}_7}\to{\mathbb{Z}_7}\),\(f(n)\equiv 2n+5\) (mod 7);\(g :{\mathbb{Z}_7}\to{\mathbb{Z}_7}\),\(g(n)\equiv 3n-2\) (mod 7).

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{12}\label{ex:compfcn-12}\)

Dar un ejemplo de conjuntos\(A\),\(B\), y\(C\), y de funciones\(f :{A}\to{B}\) y\(g :{B}\to{C}\), tal que\(g\circ f\) y\(f\) son ambos uno a uno, pero no\(g\) es uno a uno.

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{13}\label{ex:compfcn-13}\)

Demostrar parte (b) del Teorema 6.7.2.

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{14}\label{ex:compfcn-14}\)

Demostrar parte (c) del Teorema 6.7.2.

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{15}\label{ex:compfcn-15}\)

Demostrar la parte (d) del Teorema 6.7.2.

ejercicio\(\PageIndex{16}\label{ex:compfcn-16}\)

Las matrices de incidencia para las funciones\(f :{\{a,b,c,d,e\}} \to{\{x,y,z,w\}}\) y\(g :{\{x,y,z,w\}}\to{\{1,2,3,4,5,6\}}\) son\[\begin{array}{ccccc} & \begin{array}{cccc} x & y & z & w \end{array} & & & \begin{array}{cccccc} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 \end{array} \\ \begin{array}{c} a \\ b \\ c \\ d \\ e \end{array} & \left( \begin{array}{cccc} 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right) & \text{ and } & \begin{array}{c} x \\ y \\ z \\ w \end{array} & \left( \begin{array}{cccccc} 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right) \end{array} \nonumber\] respectivamente. Construir la matriz de incidencia para la composición\(g\circ f\).