3.1: El Método Euler

- Page ID

- 116959

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

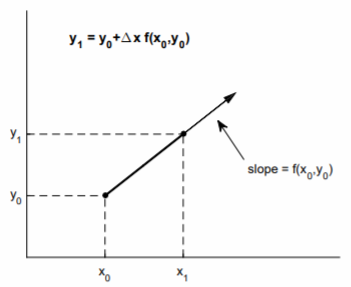

Aunque no siempre es posible encontrar una solución analítica de (3.1) para\(y = y(x)\), siempre es posible determinar una solución numérica única dado un valor inicial\(y(x_0) = y_0\), y siempre\(f(x, y)\) es una función de buen comportamiento. La ecuación diferencial (3.1) nos da la pendiente\(f(x_0, y_0)\) de la línea tangente a la curva de solución\(y = y(x)\) en el punto\((x_0, y_0)\). Con un tamaño de paso pequeño\(∆x = x_1 − x_0\), la condición inicial\((x_0, y_0)\) puede marchar hacia adelante a\((x_1, y_1)\) lo largo de la línea tangente usando el método de Euler (ver Fig. \(\PageIndex{1}\))\[y_1=y_0+\Delta xf(x_0, y_0).\nonumber\]

Esta solución se convierte\((x_1, y_1)\) entonces en la nueva condición inicial y se marcha hacia adelante a\((x_2, y_2)\) lo largo de una línea tangente recién determinada con pendiente dada por\(f(x_1, y_1)\). Por lo suficientemente pequeña\(∆x\), la solución numérica converge a la solución exacta.