7.1: Coordenadas polares

- Page ID

- 113827

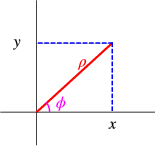

Las coordenadas polares en dos dimensiones se definen\[\begin{aligned} x = \rho\cos\phi, y= \rho\sin\phi,\\ \rho = \sqrt{x^2+y^2}, \phi = \arctan(y/x),\end{aligned} \nonumber \] como se indica esquemáticamente en la Fig. \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Usando la regla de la cadena encontramos

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}{~} &= \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial x}\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho}{~}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x}\frac{\partial}{\partial \phi}{~}\nonumber\\ &= \frac{x}{\rho}\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho}{~}-\frac{y}{\rho^2}\frac{\partial}{\partial \phi}{~}\nonumber\\ &= \cos\phi\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho}{~}-\frac{\sin\phi}{\rho}\frac{\partial}{\partial \phi}{~},\\ \frac{\partial}{\partial y}{~} &= \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial y}\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho}{~}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y}\frac{\partial}{\partial \phi}{~}\nonumber\\ &= \frac{y}{\rho}\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho} {~}+\frac{x}{\rho^2}\frac{\partial}{\partial \phi}{~}\nonumber\\ &= \sin\phi\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho}{~}+\frac{\cos\phi}{\rho}\frac{\partial}{\partial \phi}{~},\end{aligned} \nonumber \]Podemos escribir\[\begin{aligned} {\nabla} &= {\hat{e}}_\rho \frac{\partial}{\partial \rho}{~}+\hat{e}_\phi \frac{1}{\rho} \frac{\partial}{\partial \phi}{~}\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

donde los vectores unitarios

\[\begin{aligned} \hat{e}_\rho &= (\cos\phi,\sin\phi), \nonumber\\ \hat{e}_\phi &= (-\sin\phi,\cos\phi), \end{aligned} \nonumber \]son un conjunto ortonormal. Decimos que las coordenadas circulares son ortogonales.

Ahora podemos usar esto para evaluar\(\nabla^2\),

\[\begin{aligned} \nabla^2 &= \cos^2\phi\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \rho^2}{~} + \frac{\sin\phi\cos\phi}{\rho^2}\frac{\partial}{\partial \phi} {~} +\frac{\sin^2\phi}{\rho}\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho} {~} + \frac{\sin^2\phi}{\rho^2}\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \phi^2} {~} + \frac{\sin\phi\cos\phi}{\rho^2} \frac{\partial}{\partial \phi} {~}\nonumber\\ &\space\space\space+\sin^2\phi\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \rho^2} {~}-\frac{\sin\phi\cos\phi}{\rho^2}\frac{\partial}{\partial \phi} {~} +\frac{\cos^2\phi}{\rho}\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho} {~} + \frac{\cos^2\phi}{\rho^2}\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \phi^2} {~} - \frac{\sin\phi\cos\phi}{\rho^2} \frac{\partial}{\partial \phi}{~}\\ &=\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \rho^2} {~} +\frac{1}{\rho}\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho}{~} + \frac{1}{\rho^2}\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \phi^2} {~}\nonumber\\ &=\frac{1}{\rho}\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho} {~} \left(\rho\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho} {~}\right) +\frac{1}{\rho^2}\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \phi^2} {~}.\nonumber\\\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

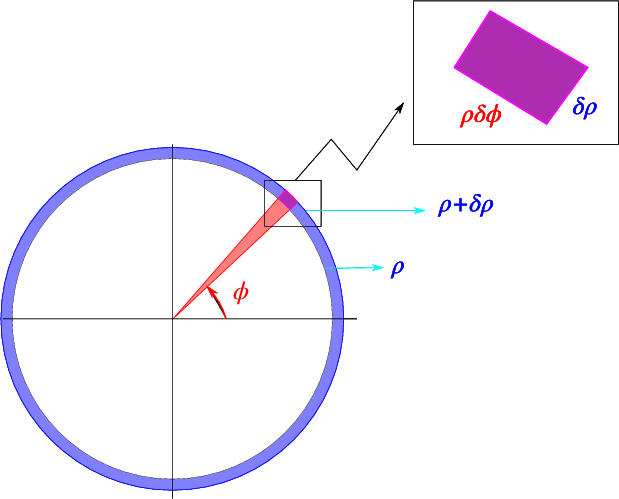

Una relación útil final es la integración sobre estas coordenadas.

Como se indica esquemáticamente en la Fig. \(\PageIndex{2}\), la superficie relacionada con un cambio\(\rho \rightarrow \rho + \delta \rho\),\(\phi \rightarrow \phi+\delta\phi\) es\(\rho \delta \rho \delta\phi\). Esto nos lleva a la conclusión de que una integral sobre\(x,y\) puede reescribirse como\[\int_V f(x,y) dx dy = \int_V f(\rho\cos\phi,\rho\sin\phi) \rho \,d\rho\, d\phi \nonumber \]